A Look at SGP-Based Rankings Using Different Projection Sets (Part 1)

The bulk of the work I do pre-draft and in-season is essentially based on an SGP (standings gain points) projections and ranking system. I use SGP data from leagues that match the format and settings of the league I’m ranking for (ideally from 10+ years of data from the actual league, where possible). While I usually do my own projections for 30-40 players of specific interest, in general I’m happy to utilize the projections published by experts that actually know what they’re doing and do it for a living. Specifically (and in no particular order) I use Steamer, Pecota, and Baseball HQ.

These lists may not be useful in ‘absolute’ terms – again, the data I’m using here reflect the SGP settings I use that reflect the league I play in. However, I still believe the lists offer an interesting way to notice a) how each projection system differs on its view of individual players, and b) general overall differences in each projection system. Blindly following a projection set is probably going to be better than randomly picking players by throwing darts at the wall. But you can squeeze a lot more value out of these rankings and the projections you use by gaining a deeper understanding of how each set of projections work, and what ‘biases’ and tendencies might be part of the numbers.

What I like to do each year is generate ‘top X’ lists of players at each position for each projection set I use, then play around in the results to spot any glaring differences. Is one projection overly conservative on expected ABs? Is one projection set basically expecting a repeat of last year’s career year? I can use that as a starting point to drill down into some of the numbers to see what might be behind the differences. Personally, I find it all too easy to get overwhelmed at all the different numbers available to be looked at – far too often I find myself deep down the rabbit’s hole, spending three hours looking at average fly ball distance on balls hit on the second Wednesday of the month on even-numbered days or something. I find this approach helps me narrow in on specific players or numbers of interest. And the benefit of doing this by SGP, broken down by category, is that it is easier to see specifically how each player is projected to impact each category. Player stats will not win your fantasy league, roto points will win you your fantasy league: I get a better understanding of the player’s ‘value components’ and how it impacts the particular league I play in.

First, a quick overview of SGP. Standings Gain Points is a way to measure the contribution of each player to your overall roto league standings. Larry Schecter’s excellent book, ‘Winning Fantasy Baseball’ is a great primer on the subject. Other places to read about SGP online are here and here. In a nutshell the system looks at the average stats needed to gain one point in the standings for a particular rotisserie category. For example, suppose in your league over the past 10 years, you needed 10 HRs to gain one point in the HR category standings. A player projected to hit 30 home runs would be credited with 3 SGPs for the HR category. Tally up all the SGPs the player is expected to add (or subtract) for all categories, and you get a total SGP score.

There’s a ton more to it, but that’s the basics – ever tried to figure out if the guy hitting a lot of HRs but no average was more valuable (and if so, by how much) than the guy hitting for a decent average and some SBs but no power? Now you have an idea.

In this first article, I look at at Catchers. I’ll add reports on all the hitter positions over the next couple of weeks. A reminder that these rankings are based on SGP values which are basically unique to my specific league, so your numbers will differ if you play in a different league format, but again, we’re looking a relative differences, not absolute numbers (For the record, the league format for the SGP rankings here: Standard 12-team 5×5 roto, 1 catcher, three OF and two util, 1250 innings cap).

Here is the list of top 12 catchers ranked by my league’s SGP, based on Baseball HQ projections:

Figure 1. Top 15 catchers by SGP & BHQ projections

| Rank | MLBAMID | Full Name | RSPG | HRSPG | RBISPG | SBSPG | AVGSPG | Total |

| 1 | 457763 | Buster Posey | 4.22 | 2.66 | 4.60 | 0.15 | 1.24 | 12.87 |

| 2 | 543228 | Yan Gomes | 4.22 | 3.08 | 4.28 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 11.84 |

| 3 | 519023 | Devin Mesoraco | 3.73 | 3.78 | 4.33 | 0.15 | -0.31 | 11.67 |

| 4 | 594828 | Evan Gattis | 3.48 | 4.33 | 4.12 | 0.00 | -0.48 | 11.45 |

| 5 | 518960 | Jonathan Lucroy | 3.98 | 2.24 | 3.84 | 0.73 | 0.62 | 11.40 |

| 6 | 431145 | Russell Martin | 3.54 | 2.52 | 3.84 | 1.02 | -0.12 | 10.80 |

| 7 | 521692 | Salvador Perez | 3.54 | 2.38 | 4.01 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 10.39 |

| 8 | 435263 | Brian McCann | 3.42 | 3.50 | 4.01 | 0.15 | -0.68 | 10.38 |

| 9 | 425877 | Yadier Molina | 3.66 | 1.54 | 3.74 | 0.58 | 0.71 | 10.23 |

| 10 | 467092 | Wilson Ramos | 2.86 | 2.52 | 3.84 | 0.00 | -0.16 | 9.06 |

| 11 | 446308 | Matt Wieters | 3.11 | 2.38 | 3.41 | 0.15 | -0.14 | 8.90 |

| 12 | 444379 | John Jaso | 3.85 | 1.54 | 3.19 | 0.44 | -0.32 | 8.70 |

| 13 | 572287 | Mike Zunino | 3.66 | 2.80 | 3.68 | 0.00 | -1.52 | 8.63 |

| 14 | 519083 | Derek Norris | 3.29 | 1.96 | 3.14 | 0.73 | -0.72 | 8.40 |

| 15 | 425900 | Dioner Navarro | 2.61 | 1.96 | 3.25 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 8.16 |

Nobody should be surprised to see Buster Posey at the top of any catchers list; he’s there because he has such a huge advantage over everyone else at the position in Batting Average. And he has a full point advantage over the next tier of players. Gomes and Mesoraco at 2nd and 3rd? Probably more of a surprise. Gomes has legit power, and the batting average isn’t a fluke (career BABIP: .323). Mesoraco had a career year last year – his 25 HRs in 440 PA is only 6 fewer than he hit in 1,100 PAs in 2013, 2012, 2011 combined. Yes, he plays in a tiny crackerjack box of a park. But his FB% jumped 10ppt (33.8% to 43%) from 2013 and 2014, while his HR/FB rate more than doubled, from a constant 10% or so in 2011-2013 to 20.5% in 2014. Color me less than convinced. And with only .44 points separating them, the next four players (Gomes, Mesoraco, Gattis and Lucroy) are basically interchangeable.

Russell Martin’s ranking gets a big boost from expected SB contribution; if those SBs dip he falls quite a bit. Would anyone be surprised if a catcher that turns 32 in February and was only 4-of-8 in stolen base attempts last year doesn’t run that much in 2015?

Conversely, if Zunino can boost his average a bit, he could be excellent late-round value. He gets a massive -1.52 hit to his SGP total after hitting less than his weight last year. On the one hand, one could possibly expect a bit of an uptick in the batting average; his BABIP last year of .248 was the lowest mark he’s recorded at any point for a full season going back to 2012 and his days in the Arizona Fall League. On the other hand, he struck out 33% of the time last year, so…yeah.

Finally – what’s surprising about this list is who’s not on it – no d’Arnaud, no Rosario.

Figure 2. Top 15 catchers by SGP & Steamer projections

| Rank | MLBAMID | Full Name | RSPG | HRSPG | RBISPG | SBSPG | AVGSPG | Total |

| 1 | 457763 | Buster Posey | 4.29 | 2.66 | 4.06 | 0.15 | 0.87 | 12.02 |

| 2 | 594828 | Evan Gattis | 4.22 | 3.92 | 4.28 | 0.15 | -0.88 | 11.68 |

| 3 | 435263 | Brian McCann | 3.85 | 3.36 | 3.79 | 0.15 | -0.54 | 10.61 |

| 4 | 518960 | Jonathan Lucroy | 4.04 | 1.96 | 3.47 | 0.73 | 0.36 | 10.55 |

| 5 | 431145 | Russell Martin | 3.79 | 2.24 | 3.19 | 0.87 | -0.81 | 9.28 |

| 6 | 518595 | Travis d’Arnaud | 3.29 | 2.38 | 3.25 | 0.29 | -0.54 | 8.67 |

| 7 | 521692 | Salvador Perez | 3.23 | 1.96 | 3.14 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 8.58 |

| 8 | 446308 | Matt Wieters | 3.35 | 2.38 | 3.03 | 0.44 | -0.68 | 8.52 |

| 9 | 543228 | Yan Gomes | 3.17 | 2.24 | 3.09 | 0.29 | -0.36 | 8.42 |

| 10 | 519023 | Devin Mesoraco | 2.98 | 2.52 | 2.98 | 0.44 | -0.60 | 8.31 |

| 11 | 467092 | Wilson Ramos | 2.86 | 2.24 | 2.98 | 0.15 | -0.03 | 8.19 |

| 12 | 425877 | Yadier Molina | 2.92 | 1.40 | 2.76 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 7.86 |

| 13 | 501647 | Wilin Rosario | 2.30 | 1.96 | 2.44 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 7.14 |

| 14 | 518735 | Yasmani Grandal | 2.98 | 1.82 | 2.71 | 0.29 | -0.69 | 7.11 |

| 15 | 455139 | Robinson Chirinos | 2.73 | 1.68 | 2.49 | 0.29 | -0.80 | 6.39 |

The first thing to notice about this list – in general the total ‘SGP’s provided are considerably lower than for the BHQ group above. At 8.90 total SGPs, Wieters wasn’t even in the top 10 in the BHQ list; 8.90 SGPs almost makes him a top-5 pick on this list. The numbers suggest that Steamer is a bit more conservative (or BHQ overly optimistic) in its forecasts, particularly for HR and RBIs. My understanding is that BHQ’s projections are largely based on playing time projections, so perhaps the numbers will change as we get closer to spring training and the start of the season and jobs are won/lost etc. It will be interesting to see how (if) these numbers change.

Looking at the list itself, Posey and Gattis again in the top five, no surprise there. McCann in the top five looks somewhat surprising (despite a rather big gap between Gattis and McCann). Maybe Steamer remembers that McCann still hit 23 HRs last year and still plays in a favorable park? His LD% was stable last year, GB% down a tick, FB% up a tick. His HR/FB rate was down quite a bit from 2013, which is surprising given that the conventional wisdom suggested he was moving to a more favorable ballpark…but his 2014 HR/FB rate was almost exactly in line with his average since 2008. Steamer might also be expecting an uptick on that awful .231 BABIP from 2014, although not sure if it’s factoring in the increased defensive shifts he saw last year. Less than .50 points separate d’Arnaud at #6 and Ramos at #11. Of the group, Wieters is now the grizzled veteran of the bunch and looked like he was on his way to a career year before getting hurt last year. If he’s healthy, he ironically could be the ‘safe’ pick of the bunch.

Grandal makes an appearance. Interestingly, Steamer is forecasting almost exactly the same number of Runs, RBIs and HRs this year – in the same number of at-bats – as last year, despite Grandal moving from a horrible Padres team (last year at least) to a much better Dodgers team (last year at least). I’d normally expect a bit of an uptick in those numbers.

Spoiler alert, but this is the only projection where Chirinos comes in the top 15; Steamer appears to be a bit more optimistic in projected at-bats, giving him a bump in Runs and RBIs that he doesn’t enjoy in the other projections.

Figure 3. Top 15 catchers by SGP & Pecota projections

| Rank | MLBAMID | Full Name | RSPG | HRSPG | RBISPG | SBSPG | AVGSPG | Total |

| 1 | 594828 | Evan Gattis | 4.41 | 4.19 | 4.82 | 0.0 | -0.6 | 12.82 |

| 2 | 457763 | Buster Posey | 4.47 | 2.66 | 4.33 | 0.15 | 0.90 | 12.51 |

| 3 | 435263 | Brian McCann | 4.10 | 3.36 | 4.12 | 0.15 | -0.78 | 10.93 |

| 4 | 431145 | Russell Martin | 4.85 | 2.38 | 3.30 | 1.16 | -1.13 | 10.56 |

| 5 | 518960 | Jonathan Lucroy | 3.98 | 1.96 | 3.68 | 0.87 | 0.06 | 10.54 |

| 6 | 518595 | Travis d’Arnaud | 3.91 | 2.66 | 3.68 | 0.15 | -0.57 | 9.83 |

| 7 | 521692 | Salvador Perez | 3.54 | 1.96 | 3.68 | 0.0 | 0.33 | 9.51 |

| 8 | 446308 | Matt Wieters | 3.66 | 2.38 | 3.57 | 0.29 | -0.77 | 9.14 |

| 9 | 425877 | Yadier Molina | 3.42 | 1.54 | 3.19 | 0.58 | 0.39 | 9.12 |

| 10 | 572287 | Mike Zunino | 3.79 | 3.08 | 3.74 | 0.29 | -1.79 | 9.1 |

| 11 | 543228 | Yan Gomes | 3.23 | 2.24 | 3.09 | 0.15 | -0.03 | 8.67 |

| 12 | 518735 | Yasmani Grandal | 3.66 | 2.10 | 3.09 | 0.29 | -0.56 | 8.58 |

| 13 | 519023 | Devin Mesoraco | 3.23 | 2.38 | 3.25 | 0.29 | -0.68 | 8.47 |

| 14 | 455104 | Chris Iannetta | 4.04 | 1.96 | 3.19 | 0.44 | -1.46 | 8.16 |

| 15 | 467092 | Wilson Ramos | 3.11 | 1.96 | 2.92 | 0.0 | -0.26 | 7.73 |

Pecota loooooves it some Gattis, putting him in the top spot over Posey. The Pecota rankings for catchers have fairly clear tiers: Gattis and Posey at the top, a substantial gap to McCann, Martin, and Lucroy, then another gap, followed by only a point or so between d’Arnaud at #6 and Iannetta at #14. Iannetta actually only shows up here because Pecota is significantly more bullish on Iannetta across the board vs the other projection sets; this almost certainly is due to differing views on ABs; Pecota’s AB projection for Iannetta is about 80 ABs higher than the BHQ projection, and over 150 more than the Steamer projection.

The difference between the Pecota numbers for Yan Gomes and the BHQ numbers are interesting – BHQ projects Gomes as one of the top 3-4 HR hitters at the catcher spot; here he’s projected to be 8th.

Martin again gets a big SB bump, which just manages to offset a rather large Avg hit (particularly compared to, say the BHQ projection, where the Avg hit was minor). Pecota is probably looking at his .290 average last year and figuring it’s a .336 BABIP-fueled fluke; Martin hadn’t had a BABIP over .290 since 2008.

Zunino again projects to have great all-around numbers except for the black hole at Batting Average. If he somehow is able to hit even .250, Zunino would likely be a top-five fantasy play behind the plate.

Looking at all three rankings, the projections differ – sometimes significantly – on some players. The BHQ-based SGP rankings loved Yan Gomes and Mesoraco; Steamer and Pecota, not so much. At the other end of the spectrum: Salvador Perez was ranked 7th in all three projection systems, largely because he’s one of the few catchers expected to make a reasonably-sized positive contribution to batting average. Although we saw last time that maybe targeting batting average wasn’t all that important…

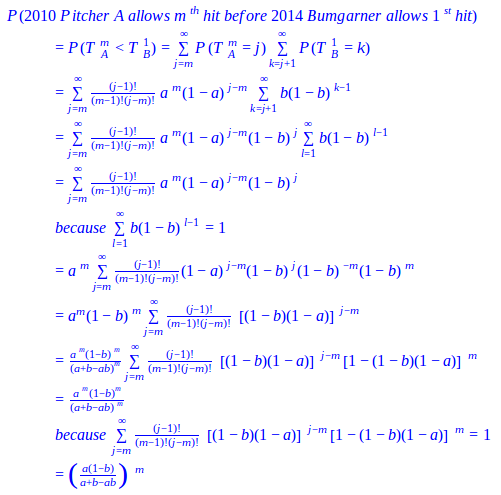

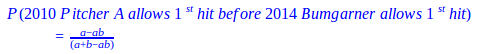

be a random variable for the total batters faced when he allows his mth hit; similarly, let b be P(H) for 2014 Bumgarner and

be a random variable for the total batters faced when he allows his mth hit; similarly, let b be P(H) for 2014 Bumgarner and  be a random variable for the total batters faced when he allows his 1st hit. If 2010 Pitcher A allows his mth hit on the jth batter, he will have a combination of m hits and (j-m) non-hits (outs, walks, sacrifice flies, hit-by-pitches) with the respective probabilities of a and (1-a); meanwhile 2014 Bumgarner will eventually allow his 1st hit on the (j+1)th batter or later and he will have 1 hit and the rest non-hits with the respective probabilities of b and (1-b). We can then sum each jth scenario together for any number of potential batters faced (all j≥m) to create the formula below:

be a random variable for the total batters faced when he allows his 1st hit. If 2010 Pitcher A allows his mth hit on the jth batter, he will have a combination of m hits and (j-m) non-hits (outs, walks, sacrifice flies, hit-by-pitches) with the respective probabilities of a and (1-a); meanwhile 2014 Bumgarner will eventually allow his 1st hit on the (j+1)th batter or later and he will have 1 hit and the rest non-hits with the respective probabilities of b and (1-b). We can then sum each jth scenario together for any number of potential batters faced (all j≥m) to create the formula below:

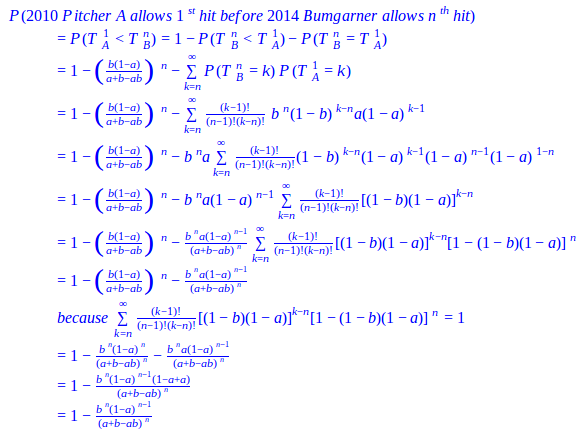

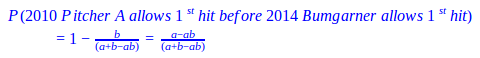

be a random variable for the total batters faced when 2014 Bumgarner allows his nth hit and

be a random variable for the total batters faced when 2014 Bumgarner allows his nth hit and  for when 2010 Pitcher A allows his 1st hit. However, instead of directly deducing the probability that 2010 Pitcher A allows 1 hit before 2014 Bumgarner allows his nth hit, we’ll do so indirectly by taking the complement of both the probability that 2014 Bumgarner allows his nth hit before 2010 Pitcher A allows his 1st hit (a variation of our first formula) and the probability that 2014 Bumgarner allows his nth hit and 2010 Pitcher A allows his 1st hit after the same number of batters.

for when 2010 Pitcher A allows his 1st hit. However, instead of directly deducing the probability that 2010 Pitcher A allows 1 hit before 2014 Bumgarner allows his nth hit, we’ll do so indirectly by taking the complement of both the probability that 2014 Bumgarner allows his nth hit before 2010 Pitcher A allows his 1st hit (a variation of our first formula) and the probability that 2014 Bumgarner allows his nth hit and 2010 Pitcher A allows his 1st hit after the same number of batters.