Last week, the Tampa Bay Times reported that the City of Dunedin and the Toronto Blue Jays put together a proposal that would keep the Blue Jays in Dunedin for another 25 years at a cost of $81 million dollars. The money invested in the project would be spent to upgrade the Blue Jays training facility, making it a year-round operating facility for the organization, and refurbish Florida Auto Exchange Stadium, expanding the stadium from 5,000 to 8,000 seats.

For nearly three years, my writing has taken a holistic view on baseball in Tampa Bay. I have taken to heart the premise of Major League Baseball and the mayors of our largest cities that Tampa Bay is a Major League region. In May of this year, I wrote an article for regional political website that asked whether local politicians believe this premise. I argued that unfortunately local politicians are acting in their own local self-interest and dividing Tampa Bay into four spring training/Minor League regions.

Last season, I wrote a post on another Rays blog that stated Tampa Bay is the fifth-most overextended sports market in America. The data for this post, from the American City Business Journals, stated Tampa Bay is currently $86 billion below where they need to be in personal income to support all the pro sports in the market. The study unfortunately did not include arena league football (Tampa Bay Storm), lower-level professional soccer (Tampa Bay Rowdies), and spring training, all of which locals in Tampa Bay spend money on.

This is why extending the Blue Jays in Tampa Bay is a bad idea. Allowing the Blue Jays to leave would allow other sports to receive fan dollars and aid their existence, removing one obstacle from an already overcrowded market. If the region values its major sports, it must allow the minor sports to walk away.

There are plenty of arguments used by the Blue Jays, the City of Dunedin, Bonn Marketing, and the team of hired economists that show why extending the Blue Jays is a good idea. This post will look at many of these points and provide alternate or opposing views.

Market Assumptions

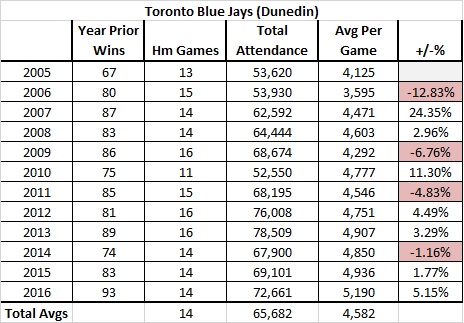

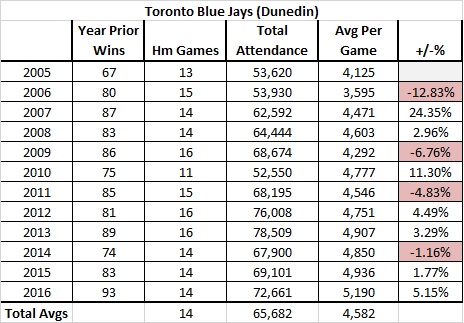

In 2016, Blue Jays Spring Training attendance increased 5%. They were the only team in the Tampa Bay area that had a spring training attendance increase in 2016. Here is the Blue Jays spring training attendance since 2005.

First, the Blue Jays had their highest attendance the same year they had their most wins in 11 years. While this is not coincidence, there is little correlation between wins and attendance in previous seasons. This year, they again have a chance to win 90 games and make the playoffs. That should bode well for spring training attendance in 2017 and we can probably predict a similar turnout to 2016.

But what happens when the Jays stop winning? Will attendance fall below 5,000 again?

Second, the released economic studies detail how valuable spring training is to Pinellas County. The study states that of the over 70,000 fans that attended Blue Jays spring training, 79% resided outside of Pinellas County. These tourists brought in $70.6 million in income to Pinellas County.

If we subtract 5% from the $70.6 2016 income, we can estimate a $67 million impact in 2015. In 2015, the tourism total for Pinellas County was $4.65 billion.

Therefore in 2015, the Blue Jays accounted for 1.4% of Pinellas County’s tourism income.

The Dunedin-Blue Jays study fails to account for the other spring training venues. If 23,539 (32.4%) of the Jays spring training attendance stayed in Pinellas County, did they see the Phillies and Yankees who also train in the local region? If the Jays left, the region might only lose one night of visitors’ stay, not the entire 7.4 nights reported. Because of the other local teams, the Jays cannot assume they are the only cause of visitors.

Next, let’s breakdown the Blue Jays 2016 spring training attendance:

- 72,652 total

- Non-county attendance: 57,395 (78.9%)

- In county attendance: 19,257 (26.5%)

- Out of state: 23,539 (32.4%)

- In state/Out of county: 33,856 (58.9%)

While we can safely assume the out of state fans stay in local hotels, what about the “in state/out of county”?

Local Spring Training Market Conflicts

Of the Jays 16 games in Dunedin in 2016, 7 were against teams with local ties (Phillies, Yankees, and Rays). Fans for those games could have either been from Hillsborough County or stayed at a hotel to also see another team’s games.

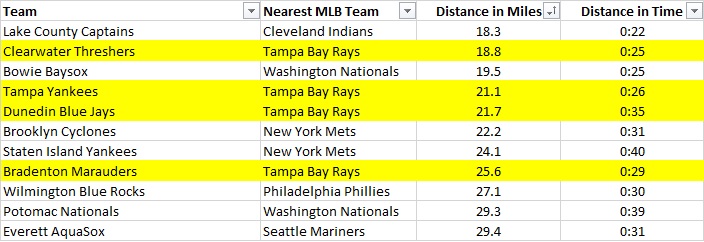

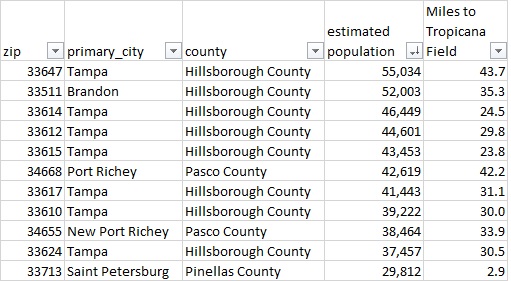

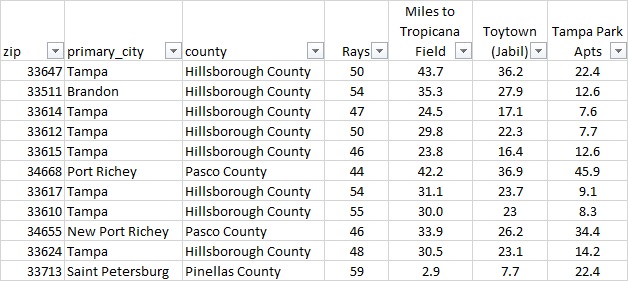

As for the 19,257 Pinellas County residents that went to see the Blue Jays spring training in 2016, their money could be spent on any other leisure activity, to include supporting the Tampa Bay Rays regular season games a month later and 21.7 miles away.

Many spring training supporters do not understand regional money spent on spring training could be spent on the Rays. They argue that the Rays don’t train in Tampa Bay, so they are not potential gainers of local spring training spending. Proponents of this view need to understand that money in hand on March 30 does not disappear on April 1. Fans of 28 other teams (Arizona excluded) wait until April to spend leisure money on baseball. If they are fans of an out-of-town team, they wait until that team visits their local team. This spending behavior is done all over the nation.

Waiting until the Blue Jays visit Tropicana Field would help the Rays’ bottom line and support Major League Baseball in the region. When locals buy tickets to spring training, they are spending their annual leisure money on a replacement good available before the premium product is released.

In 2016, the Rays accounted for 60% of all baseball tickets sold in the Tampa Bay area. This was an increase from the 58% in 2015, but far from the 71% of tickets sold to Rays games in 2009 and 2010. As a small-market team, the Rays can’t afford to have that much revenue diverted from their pockets. The Dunedin-Blue Jays agreement might even decrease the Rays percentage and give them less market share.

According to the Tampa Bay Times, 40% of the $81 million cost will go to stadium renovations. The goal is to expand capacity at Florida Auto Exchange Stadium by over 30%. If the Jays sell-out every spring training game (highly unlikely, but possible), their total spring training attendance will be 112,000. This would place the Blue Jays on level with the Pirates in Bradenton, who play in 8,500-seat McKechnie Field. Florida Auto Exchange Stadium would still be smaller than Bright House Field in Clearwater and Steinbrenner Field in Tampa.

A key missing piece in the presentations provided by the Blue Jays and the City of Dunedin is expected attendance. Where is an indicator of increased demand? Just because they’ll build it, doesn’t mean fans will come.

If fans do fill the new 8,000 facility, does the city and the team expect an increased amount of out-of-state fans to visit the new stadium or do they expect the same ratio of demand?

Using the same ratio of people from Pinellas County (26.4%) and assuming 100% sell-outs, 29,568 local residents will be spending money on a substitute baseball product in March 2019 onward. That is 10,000 more tickets purchased by money that could be going to the local Major League team.

Florida State League Market Impact

Following spring training, the facility will still be in use for the Florida State League season. Attendance for Florida State League baseball in Dunedin has been less than stellar. From 2010 to 2015, the Dunedin Blue Jays ranked last in the Florida State League in total and per game attendance. They did not rank last in 2016 due to the relocation of the Lakeland Flying Tigers to a smaller facility while their home stadium was being refurbished.

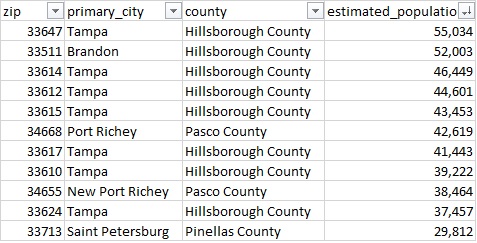

The current population of Dunedin is less than 40,000. Dunedin is one of the smallest towns in America to host a Minor League team. To fill an expanded Florida Auto Exchange Stadium would mean 20% of the entire population would have to attend. That is a huge demand for a small town.

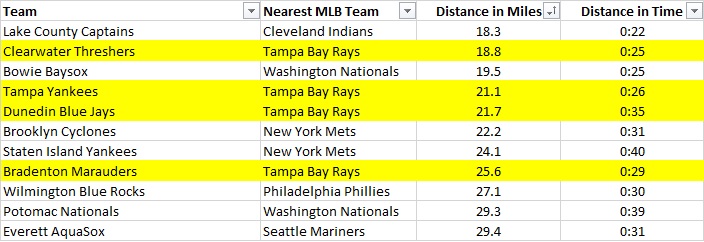

Only 5.4 miles from the home of the Dunedin Blue Jays is Bright House Field, home of the Clearwater Threshers. Although they rarely play on the same day (only seven times in 2016), these two teams are in direct competition for hyperlocal dollars. They are the same product at the same level for the same cost. The Clearwater Threshers, however, play in a stadium off a major thoroughfare and have excelled in promotions, enabling them to close in on Florida State League attendance records.

The Dunedin Blue Jays would have to increase attendance by at least 300% to match the Clearwater Threshers. Unless new fans are created, expanding Florida Auto Exchange Stadium would likely cannibalize the attendance of the Clearwater Threshers, especially when the Dunedin park is in its “honeymoon phase”.

Emotional Factors

The City of Dunedin promotes that Dunedin is the only location the Blue Jays have called their spring home in their 40-year existence. While this has emotional value, the Dodgers were in Vero Beach from 1949 to 2008 before moving to Arizona and Dodgertown was among the most revered spring training locations in Florida. Teams move; it is the nature of finding the best place for business.

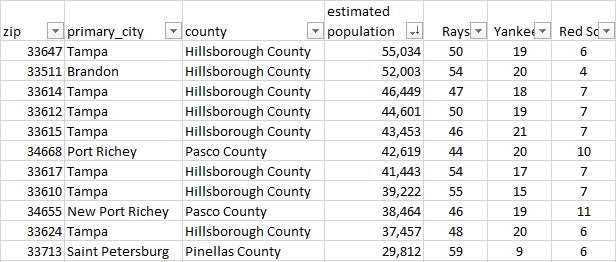

While there may be a bond between the Blue Jays and the City of Dunedin, according to polling, that bond has not translated into support for the Blue Jays. According the New York Times/Facebook survey in 2014, the top three most “liked” teams in Zip Code 34698 are the Rays (49%), the Yankees (16%), and the Red Sox (6%).

Understandably, Dunedin Mayor Julie Bujalski does not want the Blue Jays to leave. She is an elected official and maintaining the status quo is preferred to a loss that could cost her in the next election. She also doesn’t want to be the mayor who lost local revenue provided by spring training, although there is dispute whether or not revenue actually is what team-sponsored studies say it is.

On the other hand, there are many reports of areas such as Winter Haven, Florida, that have lost spring training and not suffered at all economically. University of South Florida Economics Professor Phillip Porter has been often quoted saying that “nothing changes” when a team skips town. Doubtful the City of Dunedin contacted Porter. They did however, contact Bonn Marketing, a Tallahassee, FL marketing firm that has written positive reports about spring training in Florida since 2009.

Other Blue Jays Options

Instead of reinvesting in Dunedin, the Toronto Blue Jays had several other options. They could have done any of the following:

- Move to Clearwater and split the Phillies facility

- Move to Viera, Florida where the Nationals recently vacated

- Move to Kissimmee, Florida where the Astros recently vacated

- Move to Port Charlotte and split the Rays facility

Of these options, only moving to Clearwater would keep the Blue Jays in a Major League market.

Due to the closed nature of the Dunedin and Toronto Blue Jays negotiations, we will never know what other options the Blue Jays considered. All we know is what they want in Dunedin and that Dunedin seemingly bid against itself.

Conclusion

Contrary to what the City of Dunedin, the Toronto Blue Jays, Bonn Marketing, and their hired economists have promoted, extending the Blue Jays in Dunedin is a bad idea. Until the Tampa Bay Rays are a successful franchise and have the same potential revenue as other small-market teams, local officials should decline renewal of spring training facilities in Tampa Bay. They should stop hedging their bets against the Rays and providing local residents inferior baseball goods in which to spend their money.

Even with tourism, Tampa Bay is not a big enough market to support Major League Baseball, four spring training facilities, and four Minor League teams. Declining to renew the Blue Jays and allowing them to find a new home in Florida is in the best interest of the region.