Hot Starts and Cool Finishes

When a Major League hitter gets off to a particularly good start it’s tempting to think he’s figured something out and has reached a new level of offensive performance. We want to believe. We had heard all of the “best shape of his life” stories in the spring or how a hitter is committed to using the whole field this year or how he may be working on his plate discipline. If it’s not a new level of performance we can believe in, perhaps this hitter is destined for a career year. We have hope that the good times will continue.

On the flip side, when a hitter gets off to a terrible start we worry that he’ll never figure it out. If he’s older, we may think age has finally caught up to him and this is the beginning of the end. Perhaps he can no longer hit the good fastball. Or he has to cheat to hit the fastball, so he’s susceptible to an offspeed pitch. If he’s a young player, we worry that the league has adjusted to him and he needs to adjust back. We’re pessimistic and wonder if he’ll ever come around.

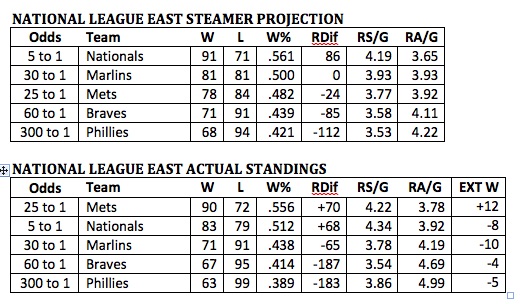

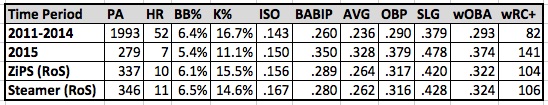

The reality in most cases is that a particular player is just off to a hot or cold start and will revert back to the player he was expected to be. It’s usually best to trust the projections. FanGraphs has projections from Steamer and ZiPS that are updated on a daily basis based on new information. During the 2015 season, I used the Steamer projections to find out what we can learn about a hitter getting off to a particularly hot or cold start.

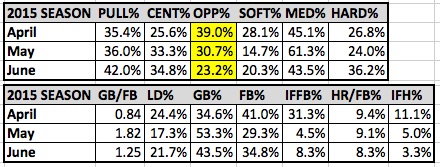

Let’s use Bryce Harper as an example. Before the 2015 season began, Harper was projected by Steamer to hit .279/.361/.487, for an OPS of .848. Through one-fourth of the season (I used May 25th, roughly the one-quarter point), Harper was hitting out of his mind: .333/.471/.727/1.198 OPS (in 191 plate appearances). The updated Steamer projection called for Harper to hit .283/.378/.515 (.893 OPS). Harper’s projected *OPS increased by .045 based on an incredible 191 plate appearances.

*I intended to use wOBA for this exercise, but I didn’t save all of the necessary stats to calculate wOBA for each time period I used last season, so OPS it is.

So what did Harper do from that point forward? He was even better than his updated projection. He hit .329/.455/.617 (1.073 OPS) after May 25th. Bryce Harper absolutely torched his updated projection. In his case, it all came together and he appears to have reached a new level of performance (he was projected for a .974 OPS heading into this season, an increase of .126 points of OPS from last season’s pre-season projection).

Of course, what is true for Bryce Harper is not necessarily true for other humans. Joc Pederson came into the 2015 season as a highly-regarded young prospect and got off to a very good start. Unlike Harper, Joc Pederson did not continue to rake. Whatever the opposite of rake is, that’s what Joc Pederson did. In fact, Pederson’s impressive first 179 plate appearances (he was hitting .250/.388/.556, with a .944 OPS through May 25th) increased his Steamer projection from a .702 OPS in the pre-season to a projected .729 OPS for the rest of the season. He actually had a .685 OPS after May 25th (hitting .193/.327/.357). In the case of Joc Pederson, you would have been better off looking at his pre-season projection than his rest-of season projection despite the additional very good early-season plate appearances.

Bryce Harper and Joc Pederson are just two of many MLB hitters. I wondered if there were any trends we could learn from this exercise, so I accumulated the necessary data during the 2015 season. I started with hitter projections from Steamer during the pre-season, then saved actual hitter statistics through May 25th, which was roughly the one-quarter point of the season for MLB teams. At the same time, I also saved the Steamer rest-of-season projections for May 26th and beyond. These projections would be compared to the actual rest-of-season statistics for each player from May 26th on.

I knew sample size would be an issue. This is just one season, after all. Also, I wanted a player to have a good number of plate appearances in the first one-fourth of the season for the Steamer projections to incorporate into the new projection. I also wanted a good number of plate appearances after the one-fourth point. I decided to use 100 plate appearances through May 25th and 100 plate appearances after May 25th as my admittedly arbitrary cutoff points in determining the sample of hitters. This left 238 hitters.

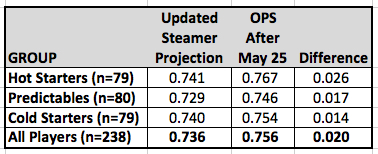

I divided these 238 hitters into three groups based on how well they hit through May 25th. There were 79 hitters who got off to very good starts, meaning their OPS through May 25th was at least .066 higher than their pre-season Steamer projection. These guys are the “Hot Starters.” The middle group of hitters consisted of 80 hitters who had an OPS through May 25th that was between -.047 and +.065 of their pre-season projection. These guys are the “Predictables.” The final group of 79 hitters had an OPS through May 25th that was -.048 or worse than their pre-season projection. These are the “Cold Starters.”

The chart below shows the pre-season OPS projection from Steamer, along with each group’s actual OPS through May 25th, and the difference between the two.

One thing to note is that all 238 players in this sample combined were projected for a .736 OPS, but had a .748 OPS through May 25th. For reference, all hitters in MLB had a .700 OPS in 2014 and .721 OPS in 2015, so the level of offense increased in baseball from 2014 to 2015 (and these hitters were selected based on playing time so are likely to be better hitters than the league as a whole). It appears that Steamer projected hitters for a lower level of offense than what actually occurred.

The Hot Starters group was very hot, with a combined OPS that was +.137 better than their pre-season projection. This group included the aforementioned Bryce Harper, along with other hot starters from last year such as Nelson Cruz, Stephen Vogt, Adrian Gonzalez, and Brandon Crawford.

As a group, the Predictables came in close to where they were projected, with a group OPS of .736 versus a predicted OPS of .730. Players who were almost spot on with their pre-season projection included Jean Segura, Kevin Kiermaier, Will Middlebrooks, and Steven Souza, Jr.

The Cold Starters group combined for an OPS that was nearly .113 worse than projected. Guys like Victor Martinez, Jayson Werth, Carlos Gonzalez, and Christian Yelich were among the biggest offenders in this group.

So how much did the rest-of-season projections change for each group? The chart below shows the same information as above in the first two columns, then adds the updated projection for each group, along with the difference between the pre-season projection and updated projection.

Notice that the Hot Starters were initially projected for the lowest OPS of the three groups and the Cold Starters were projected for the highest. After one-fourth of the season had been played, the Hot Starters group saw their projected OPS increase by .014, while the Cold Starters saw their projected OPS decrease by .011. Even after this update, the Cold Starters (with a combined .638 OPS at this point) were still projected to be nearly as good as the Hot Starters (with a combined .864 OPS through May 25th). The Cold Starters had started with a higher projection. Their lack of production through one-fourth of the season brought them down a notch, but the difference in rest-of-season projections for the hottest and coldest hitters was negligible.

As it turned out, the entire group of hitters in this sample outperformed their updated projections by .020 from May 25th on. This is not surprising when we realize that in 2015 MLB hitters did improve as the season went on, so it makes sense that the entire group of hitters would do better than Steamer projected because Steamer was likely projecting based on a lower offensive environment. MLB hitters hit even better in the second half than the first half of 2015. Here are the monthly OPS totals for MLB hitters in 2015:

April: .705 OPS

May: .712 OPS

June: .713 OPS

July: .719 OPS

August: .736 OPS

September: .737 OPS

As for the three groups of hitters in this study, the Hot Starters averaged an OPS of .767 as a group after May 25th, compared to their .741 rest-of-season projected OPS, an increase of .026, which was the largest increase of the three groups. The Predictables outperformed expectations by .017, and the Cold Starters were better by the least amount, at .014.

At this point, it looks like early-season hot hitters are more likely to beat their updated rest-of-season projection going forward. In this case, the Hot Starters and Cold Starters were given rest-of-season projections that were very similar (.741 and .740), but the Hot Starters out-produced the Cold Starters by .012 points of OPS. We might be on to something here. Before we dive further into this, let’s check up on our old friend “regression to the mean.”

The following table shows what percentage of players from each group improved after May 25th and what percentage performed worse after May 25th.

As you would expect, the majority of the Hot Starters (82%) couldn’t keep up their hot hitting. Notable exceptions included Joe Panik, A.J. Pollock, and Lorenzo Cain. Panik was projected to have a .641 OPS in the pre-season. Through May 25th, his OPS was .773, which made his updated projection .657. Instead of coming back down to earth, Panik took his offense to another level, producing an OPS of .875 after May 25th. A.J. Pollock was similar, but at an even higher level of production.

While the majority of Hot Starters couldn’t keep up their torrid pace, most of the Cold Starters (78%) turned things around after May 25th. Three who did not improve were some of the biggest hitting disappointments in 2015—Mike Zunino, Pablo Sandoval, and Wilson Ramos. All three started poorly and didn’t get any better over the last three-fourths of the season.

In the Predictables group, the king of consistency was Buster Posey. Posey was projected for an OPS of .840. Through May 25th, his OPS was .850. This increased his rest-of-season projection to .845. He produced an OPS of .849 after May 25th. Buster Posey was a human metronome in 2015.

Okay, let’s go back. I had arbitrarily divided these hitters into three groups and came up with these initial results that appear to show that hot hitters stay hotter than their updated projection would expect. What happens if I divide them into four groups?

Oh.

The column on the far right of the top chart is key here. Based on my results when the hitters were divided into three groups, I expected the Scorching hot hitters in this sample to stay hotter than the other three groups, meaning I expected them to outperform their updated rest-of-season projection by the largest amount. They did not. The Hot and Chilly hitters both improved on their updated rest-of-season projections by a greater amount than the Scorching hitters. The Chilly group of hitters were the worst of the four groups through the one-fourth point of the season (a combined .629 OPS), but actually had the highest OPS over the final three-fourths of the season.

On the bright side, the second chart came out as expected. The hitters who started out the year the hottest were the least-likely to improve after the one-quarter mark. The second-hottest hitters were the second-least likely to improve. The pattern follows for the Cool and Chilly hitters.

I did one final check with just two groups—those who had a higher OPS through May 25th than they were projected for in the pre-season and those who had a lower OPS through May 25th than they were projected for in the pre-season. That chart is below:

The Above Projection group started the year with a projected OPS of .731. Through May 25th, these hitters combined for an .823 OPS. Their updated projection was .739. After May 25th, they had a .761 OPS, which was .022 higher than their updated rest-of-season projection. The Below Projection Hitters ended up .015 higher than their updated rest-of-season projection.

This shows a slight trend towards the early season hot hitters outperforming their projection, but the difference is just .007 points of OPS and if Bryce Harper is removed from the Above Projection group, the difference drops to .005. If there is a trend, the difference is small. The important takeaway, as the second chart shows, is to trust that most of those who start out hot will cool down and most of those who start out cold will heat up.