Umpires Disproportionately Eject Non-White Players

Anthony Rendon was ejected from a game earlier this month for … not contesting the strike zone. He flipped his bat down, faced away from the umpire, and did not visibly open his mouth. He was tossed by Marty Foster, for, what crew chief Joe West described incorrectly as ‘throwing equipment.’ (The pathologization of a non-white player’s actions after the fact to justify an ejection by a white ump is the subject of an entirely different set of analyses.)

After the game, Rendon actually went on record to say that umpires, like players, should be held to specific standards and demoted if they fail to meet those standards. This statement is remarkable for a couple of reasons. One, as most Nats fans know, getting Rendon to say anything, particularly anything of substance, to the media is pretty tough. He is, to forgive the pun, a pretty close-mouthed guy. For another, he points out that umpires, like players, are now doing their jobs in the Statcast era – we know, to a pretty refined degree, how well or not well they’re performing.

Players can be subject to replays that will tell them if their hand left the bag for the fraction of a fraction of a second, such as what happened to Jose Lobaton for the last out in the 8th in 2017 NLDS Game 5 (stay salty, my friends). But a home plate umpire’s word, particularly about the strike zone, is law. I understand ball vs. strike calls not being subject to replay. Even as someone who thinks most of the league’s pace-of-play ‘innovations’ are utter nonsense, I can’t see a good system in which every pitch could be subject to review. (Though, if the manager could make it one of their challenges, that’d be a start.) Umpires, therefore, should be held to the same standards, including performance reviews, as the players whose games they call.

The other thing that makes Rendon’s statement noticeable is that he’ll be facing the same umpiring crew in the final game against the Mets of this series and is likely to face them again this season. Saying that an umpire isn’t, in effect, doing their job commensurate with how Rendon is doing his is putting a pretty wide target on his own, and his team’s, back.

But beyond this instance, Rendon’s relatively mild approach to being struck out looking was disproportionately punished. He was ejected for not doing a whole heck of a lot, a punishment that seems incredibly disproportionate to a ‘crime’ that didn’t seem to go against MLB rules, written or unwritten.

I quickly tweeted out asking for an analysis of non-white versus white players in similar circumstances, because I had a hard time picturing a white player (like, say, Kris Bryant) being tossed for the same thing. Since no analysis existed, I did my own.

My analysis of available player ejection data from 2015-2017 led to the unmistakable conclusion: Non-white players, and Latino players in particular, are tossed at rates completely disproportionate to their representation in the league.

Methodology

Here’s a spreadsheet of data I compiled, mostly using Umpire Ejection Fantasy League data. I decided to limit it to 2015-7, in part because of use of Statcast and relatively consistent replay rules.

I also came at this analysis assuming any particular non-white and Latino player was as likely as any white, non-Latino player to be ejected, and so compared player ejections with league representation percentages for particular ethnicities. However, in doing analysis on position players only – that is, excluding pitchers – I didn’t have the league representation percentages adjusted for position players.

A major limitation in my data is having to hand-assign players as being white or non-white, and Latino or non-Latino. This was done using country of origin and knowledge of US-born players, and therefore is limited by my personal knowledge, particularly for US-born players. For instance, Marcus Stroman’s mother is from Puerto Rico and he was offered the chance to pitch for Team PR in the WBC. For the purposes of this analysis, he was classified as ‘nonwhite’ and ‘Latino.’

I also don’t know how players self-identify; I’m assuming Anthony Rendon, whose family is from Mexico and who was offered the opportunity to play for Team Mexico, self-identifies as Latino, but I don’t know if he’s stated that specifically. For non-US-born players, I also classified all players born in Latin American countries as Latino, but again, that’s not the same as asking for someone’s self-identification and that’s not the same as how any particular umpire perceives any particular player. For example, Francisco Cervelli, who is Italian and Venezuelan, was classified as non-white and Latino for this analysis.

I also classified Latino players as ‘non-white’ for the purposes of this analysis. While many Latinos self-identify as white, the Racial and Gender Report Card for Major League Baseball, where I got the league demographic data, identifies them as non-white and calculates them in the total of ‘players of color.’ So I maintained this classification for the purposes of this analysis. Any mistakes are unintentional; I welcome comments with suggestions for re-categorization.

Lastly, the umpiring corps has, as far as I know, not changed dramatically year to year. It’s a notoriously narrow pipeline and one almost entirely composed of white men. Analysis showed that some umpires toss players more than others, but this hasn’t been controlled for brawls. Additionally, the numbers of players tossed is a reflection of the number of games worked, which I haven’t controlled for.

This analysis isn’t meant to ascribe ejecting non-white and Latino players to any particular bad actor within the umpiring corps but to show a pattern of behavior.

The data:

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Grand Total | |

| Non-white | 50 | 52 | 29 | 131 |

| Latino | 39 | 42 | 22 | 103 |

| Non-Latino | 11 | 10 | 7 | 28 |

| White | 50 | 38 | 44 | 132 |

| Non-Latino | 50 | 38 | 44 | 132 |

| Grand Total | 100 | 90 | 73 | 263 |

Non-white players being ejected accounts for almost 50 percent of total ejections, despite players of color never being more than 42.5 percent of the league. Latino player ejections account for 38 percent of ejections, despite Latinos never being more than 31.9 percent of the league. Non-white, non-Latino players (of whom most are African-American), accounted for about 11 percent of ejections, fitting with representation in the league, except that no Asian players were ejected in this time period, and Asian players made up between 1.2 and 1.9 percent of the league. So, non-white, non-Latino, non-Asian players make up about 9-10 percent of the league and 11 percent of the ejections.

2017 is, therefore, a bit of a fluke. Of total players, nonwhite and Latino players were actually not tossed any more often (relative to their representation in the league) than their white peers.

| Percentage of Total Ejections | 2017 | Percentage of the League |

| Non-white players ejections | 39.7% | 42.5% |

| Latino players ejections | 30.1% | 31.9% |

| Non-white, non-Latino players

ejections |

9.6% | 10.7% |

| White players ejections | 60.3% | 57.5% |

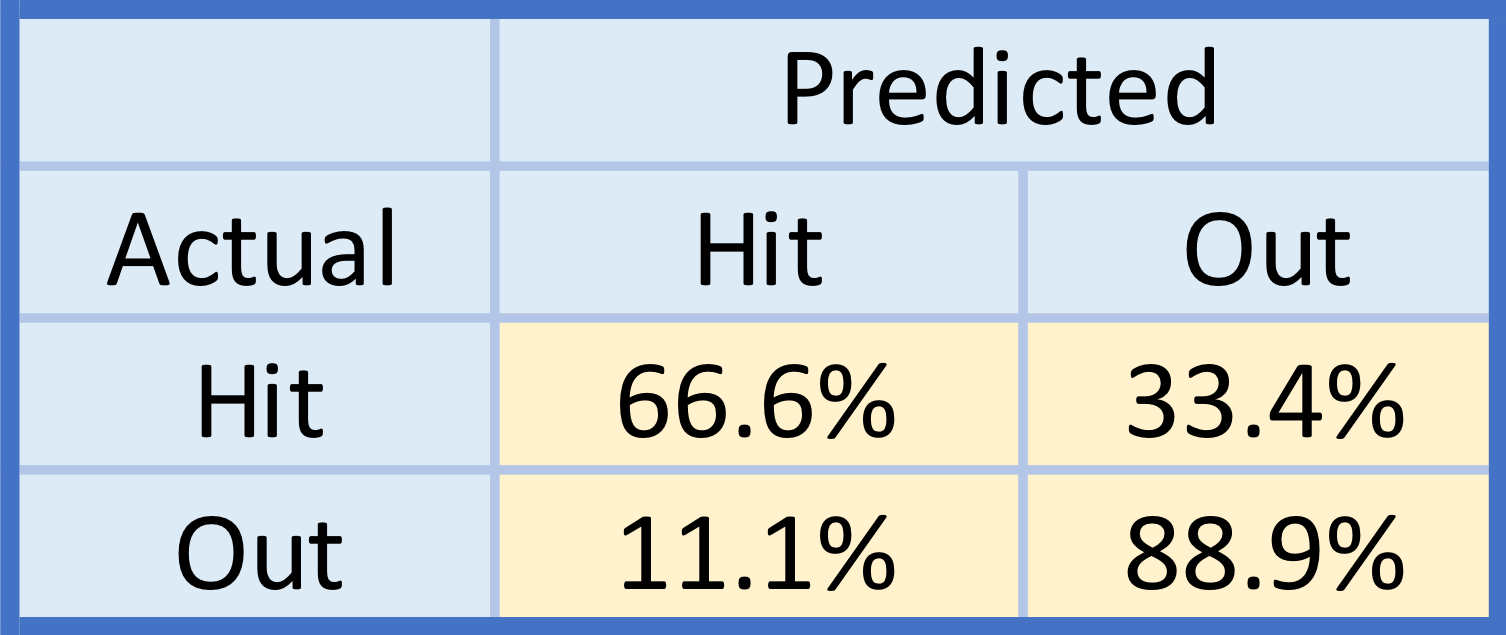

I then controlled for two things: pitcher ejections and ejections by non-home plate umpires, figuring that most pitcher ejections were as a result of beaning batters (which, yep, keep tossing them), and non-HP ejections might result from ejections during brawls, arguing slide calls, or in circumstances dissimilar to Rendon’s.

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Grand Total | |

| Nonwhite | 31 | 36 | 26 | 93 |

| Latino | 23 | 26 | 19 | 68 |

| Non-Latino | 8 | 10 | 7 | 25 |

| White | 26 | 26 | 32 | 84 |

| Non-Latino | 26 | 26 | 32 | 84 |

| Grand Total | 57 | 62 | 58 | 177 |

A few things became noticeable. One, overall ejections seem to be dropping, but non-pitcher, HP umpire ejections are holding pretty steady. Two, in 2015 and 2016, non-white position players comprised the majority of ejected players. Not only were non-white position players being ejected at a rate disproportionate to their representation in the league, they were being ejected more often than their white peers.

Latino position players were also being ejected by home plate umpires at rates disproportionate to league representation in 2015 and 2016 – 40 percent of ejections in 2015, despite Latino players being 29 percent of the league, and 42 percent of ejections in 2016, despite being 28.5 percent of the league.

For 2017, non-white and Latino players were ejected slightly more frequently than representation would account for.

| Percentage of Total Ejections | 2017 | Percentage of the League |

| Non-white players ejections | 44.8 | 42.5 |

| Latino players ejections | 32.8 | 31.9 |

| Non-white, non-Latino players

ejections |

12.1 | 10.7 |

| White players ejections | 55.2 | 57.5 |

So, is 2017 a step in the right direction or a flukey year or something else? No idea, and with the 2018 season being nascent, it’s hard to say. If there have been interventions on the part of the MLB or the umpire’s union, fantastic, but those interventions have not, as far as I’m aware, been made public.

I also know we won’t know for a while about 2018 ejections because ejections aren’t all timed equally. One of the weird things about this data is that white players tend to be ejected in early months, and non-white and Latino players make up the majority (or at least a disproportionate percentage) of ejections after May.

| April | May | June | July | August | Sept. | October | Grand Total | |

| Nonwhite | 14 | 17 | 27 | 24 | 22 | 25 | 2 | 131 |

| White | 18 | 37 | 16 | 15 | 19 | 24 | 3 | 132 |

| Grand Total | 32 | 54 | 43 | 39 | 41 | 49 | 5 | 263 |

| April | May | June | July | August | Sept. | October | Grand Total | |

| Latino | 10 | 14 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 21 | 2 | 103 |

| Non – Latino | 22 | 40 | 25 | 19 | 23 | 28 | 3 | 160 |

| Grand Total | 32 | 54 | 43 | 39 | 41 | 49 | 5 | 263 |

What this means is that the early ‘eye test’ for white and non-white players being ejected at similar rates won’t bear out in later months.

What if they deserve it?

None of this has addressed a fundamental question in considering ejections: Some guys have it coming. I tried to control for this in considering repeat offenders – that is, if there are certain players who, by virtue of reputation and absent any racial dynamics, just get tossed a lot.

Of the guys who’ve been tossed more than three times, the results are … very unsurprising:

| Ian Kinsler | 4 |

| Josh Donaldson | 4 |

| Mike Napoli | 4 |

| Matt Kemp | 5 |

| Yunel Escobar | 5 |

| Bryce Harper | 7 |

Of these repeat offenders, Escobar and Kemp are non-white, and the former is Latino. The rest are the kind of love-’em-or-love-to-hate-’em white guys you might expect to make up such a list. So again, the eye test of ‘Bryce gets tossed too,’ doesn’t bear out when you look at the number of different players tossed total.

For ‘three-peaters’ – guys tossed 3 times in the past three seasons – of the 13 tossed three times, only two, Joey Votto and Justin Turner, aren’t Latino. And for players tossed once or twice – so not for having a rep as a showboat or arguer or ‘disrespectful’, 57 Latino and 115 non-Latino players have been tossed in 3 years. So, 33 percent of ejections have been for Latino players, despite the fact that Latinos averaged at 30 percent of the league’s players during this time. For non-white players, 76 non-white and 96 white players were ejected once or twice, meaning 44 percent of players ejected once or twice weren’t white, with the league averaging 41.5 percent non-white players during this time.

In totality, 36 percent of the players being tossed are Latino, and 46.5 percent of the players being tossed are non-white, both higher than their representation in the league.

If ejections are the league’s way of dealing with argumentation at the plate, we should consider that Latino players and non-white players are already disproportionately disciplined by their fellow players – and brawls are more likely to break out between players of different ethnicities.

We should also consider why players are perceived to ‘have it coming’ to them for arguing, ‘showboating,’ or other displays of either enthusiasm or disrespect, depending on your perspective, and why Latino and non-white players are dinged for it so more than their white peers for what are likely similar behaviors.

Umpiring by largely white umpires on increasingly non-white players is a cross-cultural conversation, one that’s monitored by 40,000 fans, TV viewers, and the ever-watchful eye of Statcast. The league has a vested interest in solidifying its presence in Latin American countries and in trying to encourage African-American players – who are a decreasing percentage of players overall – to continue with the game.

I don’t pretend to know what’s in an umpire’s heart (I assume pine tar and certificates for failed eye exams). I didn’t do this analysis to say that any particular umpire is actively thinking that they should eject a non-white or Latino player because they are non-white or Latino. What I discovered in doing all of this is that there is a very clear pattern of behavior among umpires when it comes to player ejections when the Statcast era is taken in its totality. An action may cause harm – in this case, an ump being more likely to throw out a non-white player – without any specific racist intent.

Additionally, the idea that umpires are enforcing ‘respect’ (and Joe West said that was Foster’s intent in tossing Rendon – “You have to do something or he loses all respect from the players.”) on non-white and Latino players is particularly galling. If non-white and Latino players are disproportionately perceived as ‘disrespectful’ of the game for similar actions as their white peers, such as tossing a bat after a strikeout, then the issue is perceptions and not players.

This, of course, is a societal issue beyond baseball. Analyses of behavioral perception by white teachers show that they tend to ascribe disrespectful, aggressive behaviors to non-white students at higher rates than they do to white students or than black teachers do with black students. Analysis of school punishments shows that black and Latino students are suspended and expelled at much higher rate than their white peers without any evidence they’re misbehaving more. So this is not a problem unique to player-umpire dynamics, but instead is one indicative of broader structural societal dynamics.

To work on addressing this as a structural issue, the league can change how it handles ejections. A few proposals:

- All plays over which a player is ejected are automatically reviewable, including balls vs. strikes. If an umpire ejects a player on a strike call that, on review, is revealed to be a ball, the player isn’t ejected. If a player makes contact with an umpire, they should be ejected but if players see that there is a clear and objective appeals process to an ejection, my guess is that they’re more likely to calmly walk off than explode.

- All ejections should be reviewed as part of a rigorous rating process for umpires. Umpires who repeatedly eject players for calls that, on review, they should not have made (such as a bad ball vs. strike call) should experience some form of penalty – by being demoted, retrained, or fined.

- Umpires’ ability to call balls vs. strikes compared with what Statcast determines is in or out of the zone should be made publicly available. If an umpire is consistently below a certain percentage of accuracy, they should be demoted or retrained.

- Player strikeout rates should be adjusted for umpire accuracy the way player defense is adjusted for particular ballparks.

- Diversify the umpire corps. Currently, umpires are generally older white men who feel tasked with enforcing ‘respect’ from young, increasingly non-white players. I’m not saying that simply hiring more people of color (including women of color) is a cure-all for these kinds of issues, but diverse perspectives may mean a decrease in unintended slights between players and umpires, and a general change in player-umpire dynamics.

- Radically, I would also like strike calls to be reviewable. They would cost a manager a challenge if incorrect like any other play. If a manager challenges – and is correct in challenging – strike calls repeatedly, then the umpire, and not the player or manager, should be held at fault.

If this sounds like we can replace a home plate umpire with Statcast for calling balls vs. strikes, then I’m for it. As the cliche goes, I didn’t watch the game for the umpiring, and if a computer can do what the umpires are doing in a fashion that doesn’t disproportionately penalize players of color, then I don’t see a downside.

I co-host Resting Pitch Face, a bi-weekly baseball podcast with a Nationals bias. I can be reached on Twitter at @sydrpfp.