Ozzie Albies has been at the heart of his team’s unexpected push for the NL East division lead all season. He was there before Ronald Acuña came up. He’s been healthy since Acuña got hurt. He blasted through April with a triple slash of .293/.341/.647. A .647 slugging percentage! Everyone was astounded. Articles were written about how rare and mystifying it was, whether it was sustainable, and how it was nearly impossible to provide a comp for him because there hasn’t been a player like him before. He appeared to be imposing his will on anyone who dared to pitch to him.

Well, gang, May happened. And June is in the midst of happening. And while his overall performance to date still provides us great insight to the player we can look forward to, Albies has had a much tougher go of things. That triple slash slunk to .264/.306/.432 in May. So far this month, it’s at .154/.200/.346.

The good has been unprecedented; the bad has turned abysmal. Each has been more extreme than his profile ever seemed to offer. When Albies was first called up last year, Baseball Prospectus said he “has a slash-and-dash offensive approach that marries well with his advanced bat control and plus-plus speed.” But since he’s been in the Bigs, he’s been more of a free-swinging, freewheelin’ monster.

In 2017, he offered at more than 51% of the pitches he saw. Had he qualified, that would’ve placed him in the bottom 20% of the league, in the company of Yangervis Solarte and Brandon Crawford. This season he’s been even more severe, swinging at more than 55% of all pitches faced. That puts him in the bottom 5% of qualifiers. So, really, what is going on?

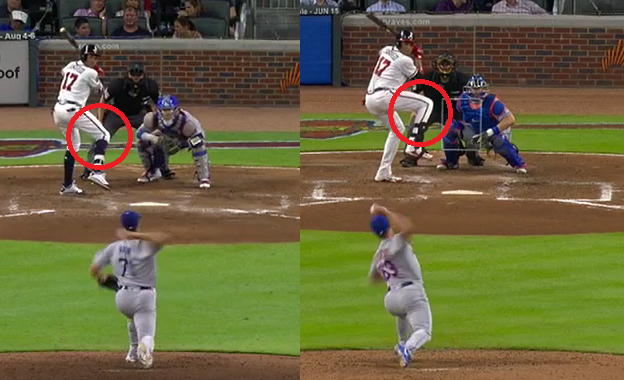

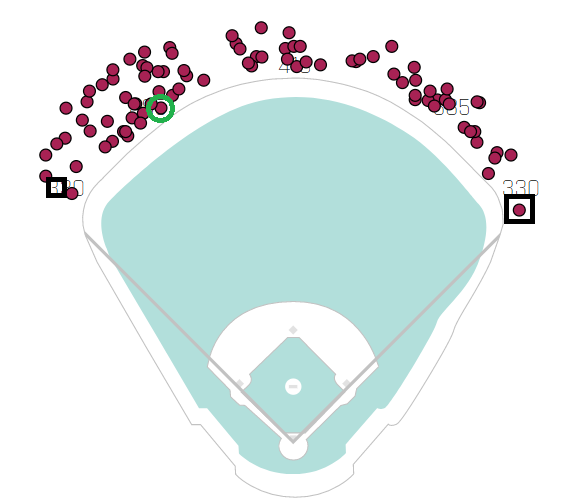

This gif shows the plate from the catcher’s view, and consists of only lefthanded plate appearances by Albies. It accounts for about 70% of his plate appearances and is where the struggles have really come in, as he’s hit only .232 from the left side as opposed to .318 from the right.

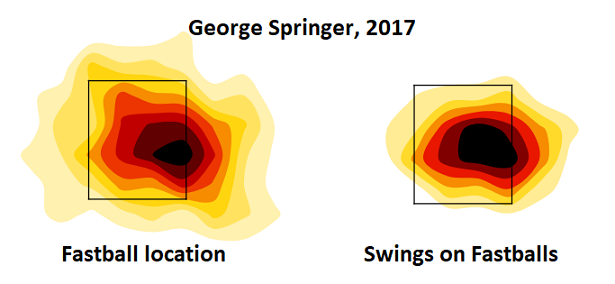

On the left side of the gif is a heatmap of Albies’s swing percentages. On the right is where pitchers have located to him. The first is through April, and the second is from May through 6/14. At the start of the season, pitchers filled the zone and challenged him. Per Baseball Savant, more than 41% of pitches he faced crossed the plate that month, and he used his exceptional bat control to punish those balls. However, since May, pitchers have thrown it in the zone far less — a shade under 33% of their total pitches to him. When you’re swinging at more than 55% of the pitches you’re seeing, but only one in three is over the plate, you’re bound to run into trouble.

There are two possible suggestions to make for Albies here. One would be mechanical, assuming something is wrong with his swing. That would probably be premature, given how good he’s been at such a young age. The other would be mental, which seems more likely. His advanced bat control appears to have convinced him that he can hit anything, so he’s going for it. But by doing so, he might be poorly manipulating the signals in his brain he uses to make contact.

Bijan Pesaran, a professor of neuroscience at New York University, explains it this way through the scope of ping pong players:

“When [they] are playing at a high level, they look at the ball up to the point where they hit it. As soon as the paddle makes contact with the ball, you can see their eyes and head turn to now look at their opponent. They think they are looking at their opponent when they are hitting the ball, but they are looking at the ball. Their eyes are tracking the ball, even though they are aware of their opponent.”

Pesaran also says that the cerebral cortex is arranged more like a mosaic than a traditional puzzle. That’s the part of the brain ballplayers would use for pitch recognition and location. If Albies is going to parts of the zone he’s unfamiliar with — parts he doesn’t approach when he’s hitting at a high level — he’s essentially attempting to rearrange the mosaic network that relays the signals from his brain to his swing. It also means he could be looking at the ball longer since he’s not used to seeing it in those places.

The result is a hitch in the 200 millisecond cycle where his brain processes a pitch and tells his body to swing, which may be causing, or at least contributing to, the struggles in which Albies finds himself swamped.

Ozzie Albies didn’t suddenly turn into a pumpkin after a flare of greatness. He’s too good for that. But he does need to adapt to a league that’s already adapted to him. His next step forward could take realizing his limits.

—

Pitch charts from Baseball Savant. All other data from FanGraphs. Gif made with Giphy.