A Peek into the Astros’ Secret Sauce for Pitching

The Franklin Institute is a science and research museum located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Among its many draws are a giant heart you can walk through, the SportsZone where you can sprint the 40-yard dash and compare your time to professional athletes, and a Changing Earth exhibit made entirely of sustainable materials that focuses on the ways the planet has transformed over time. Through all of that, plus rotating feature exhibits, it’s easy to lose sight of a tried and true experiment: The Ruler Drop Test.

If you never performed the experiment in middle school, the Ruler Drop Test is exactly as it sounds. Take a ruler — or, in the case of the Franklin Institute, a yardstick — and hold it vertically between your index finger and thumb on your dominant hand, about one-fourth from the bottom. Then release it and see where you can catch it. The shorter the distance between where you let go and where you catch it, the faster your reactions are. Science!

It’s a simple experiment, but it is illustrative. And with how it’s centered on vertical drop and expectations, it could help us understand how the Houston Astros have used advanced technology and data to tweak pitchers’ repertories to reach new levels of success.

The league-average pitching staff has put up a shade over 14 fWAR per season since 2016. Meanwhile, the Astros have averaged five wins more than that over the same span, capping it off last year with a bat-guano crazy 30.6 fWAR. The organization clearly knows something about pitching that the rest of the league hasn’t figured out yet. Justin Verlander and Gerrit Cole are second and fifth in pitching fWAR for the team since then, despite only combining for two seasons (and a month) as Astros. Here’s a big part of why:

Both Verlander and Cole came to Houston and changed. On the left in this gif is each pitcher’s breaking ball release point in the season before they got to Houston. On the right is those pitch release points after becoming an Astro. The change is two-fold: the release point on each has tightened up, and curveballs have become more distinguished and over-the-top.

One possible explanation could be how the team uses Edgertronic cameras to fight a pitcher’s intuitive notion of knowing exactly how the ball is leaving their hands. The high-speed cameras can capture thousands of frames per second. A pitcher using one means they can see exactly when the ball leaves their hands, where they last put pressure on it and with which finger(s), and how their wrist either pronates (meaning the palm moves inward, like with a curveball) or supinates (meaning the palm ends up facing outward, like with a changeup). It’s the kind of tech that teams are racing to incorporate just so they don’t get left behind at this point, and the Astros have been using it longer than anyone.

There may not be another way of getting so granular with technique that makes it equally easy to understand in a matter of seconds. It’s almost a paradox. It’s not that Justin Verlander and Gerrit Cole weren’t good, but their abilities clearly weren’t optimized, and this is something we can only truly appreciate after seeing them take a step up we couldn’t even tell was there.

By cleaning up their release points and deliberately going over the top with their curveballs, each pitch became more devastating because it started falling off the table more. Their wrists may have started staying locked instead of leaking out toward third base. Verlander’s slider has gained more than two inches of drop, while his curve has gained more than an additional inch. Cole’s slider has actually lost about half an inch of drop, but his curveball has tumbled two-and-a-half inches more.

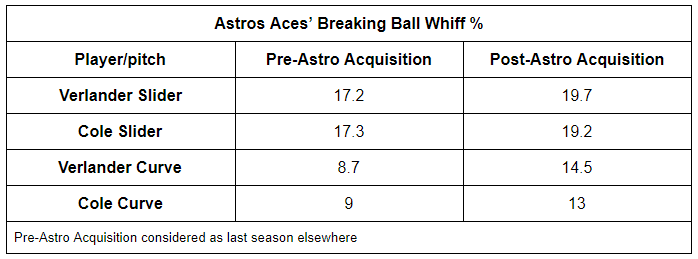

Those numbers sound well and good, but the results are plain eerie.

The league-average whiff rate for sliders is 17%. For curveballs, it’s 13%. Houston acquired two really good power pitchers, made the same tweak to each, raised their whiff rates on one pitch from average to above, and their whiff rates on another from below average to average. These are the kinds of incremental improvements a team would be happy to take one at a time, from one average player at a time. They basically made both tweaks at once in back-to-back seasons with two guys who have elite talent. It seems there are times when we run out of superlatives to describe the Astros, but this is eye-popping.

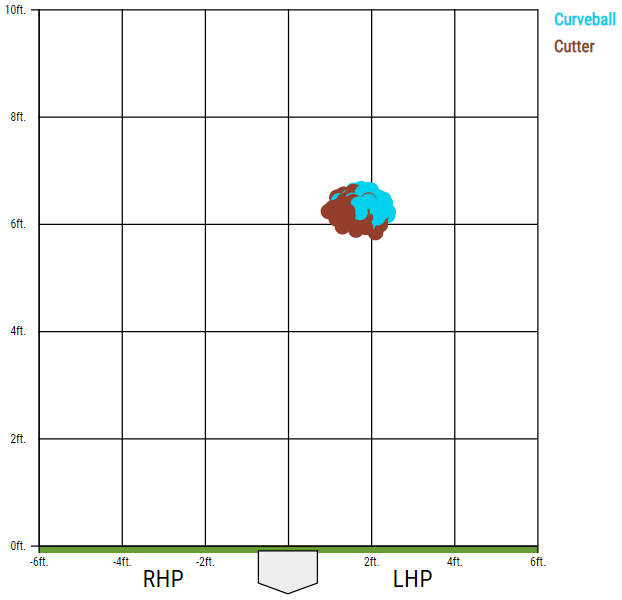

It may also serve as grounds for how the team could tweak Wade Miley, who added a cutter last year that helped him tally 1.5 fWAR in just half a season’s-worth of starts with the Brewers. Below are his release points for the pitch compared to his primary breaking ball, which was a curve.

There are differences when you compare Miley with Verlander and Cole, and they’re obvious. He throws about 7 mph slower than either of them. He doesn’t have two breaking balls like they do. These are no small things, but a cutter can be a bit between a fastball and a slider, and bringing his curveball release over the top may help both pitches play up.

Even if last year’s numbers were flukey — his cutter, while useful, generated whiffs well below average — a rate of improvement from Miley comparable to Verlander’s and Cole’s could see him become a league-average pitcher who helps steady a staff that’s going to have a lot of turnover in 2019. The aces are still there, but Lance McCullers will miss the year with Tommy John, Dallas Keuchel’s on the open market, and Charlie Morton already left for Tampa Bay.

Let’s bring it all back to the Ruler Drop Test. When you perform it, you know the weight of the item you’re dropping. You’re almost completely still, save for a couple fingers releasing and pinching. It’s moving extremely slow. The environment is almost completely controlled.

Now, as a hitter, speed up the moving object to 80-plus mph. Throw in a variable, downward path and less predictable, more severe vertical movement. And you’re not just catching the object with two fingers. You have to use your whole body in a smooth kinetic sequence to “catch” it with your bat. The Astros have taken what we know about the game environment and found a way to exaggerate its difficulties for the opposition by way of the breaking ball’s drop.

Maybe it’s not the full recipe to Houston’s secret sauce for pitching. But this basic test combined with the specific improvements from Justin Verlander and Gerrit Cole helps us get a grip on what the team does so much better than the rest of baseball.

Pitch movement data from Brooks Baseball. League-average whiff rates from Alex Chamberlain. Pitcher-specific whiff rates and release points from Baseball Savant.

Tim Jackson is a writer and educator who loves pitching duels. Find him and all his baseball thoughts online at timjacksonwrites.com/baseball and @TimCertain.

Good stuff.

Good strategy and scouting,finding guys who you think can get to another level with tweaks.Got Cole for basically nothing(unless Musgrove breaks out) because he wasn’t performing like Hou thought they could get him to,If Pittsburgh was maximizing his potential and he pitched like he is with Hou they would of got alot more back for him if not from Hou from someone else

Great insight. Thanks. Has anyone looked at K/B rate as a function of this sort of change.

I’m not sure, but that’s a great idea.

Great article. Are you sure you have pronate and supinate correct?

Google tells me yes? But if I goofed it, let me know, because that’s important