Fast, for a Catcher: Analyzing a Quickly Moving Backstop Market

Have you ever had a baseball game on in the background in the dead of summer as you quietly go about your day, and then you catch an absolute gem from a broadcaster that stops and makes you laugh? “He got down the line in a hurry… He’s pretty fast, for a catcher.”

It’s possibly the game’s greatest backhanded compliment; an ode of sorts to the frequently lumbering yeoman who not only endure the dog days of August but who do so willingly, wearing additional gear and sitting in an awkward squat for hours. A single sentence about their baserunning abilities — or lack thereof — conveys perhaps a modestly complete understanding of what baseball is, when you stop to think about it. And it’s a delight.

This offseason has seen a different kind of speed from catchers: the one at which they’re changing teams. Maybe it’s coincidence that some of the more offensive-minded ones have reached the market together, and they’re some of the names moving between teams. While backstops make it difficult to capture their entire value in a single stat because of all they do, we can and do quantify offense. That makes it easier, if you’re a front office, to jump on a guy you know can beat the .232/.304/.372 average triple-slash line catchers produced in 2018 and see it as a win.

But the offense-oriented catchers aren’t the only ones moving between teams, and it becomes harder to separate them from each other when considering defense or the total package. It is much harder than separating, say, Mike Trout and Charlie Blackmon. And that’s what makes the catcher carousel this offseason a unique ride.

In each instance of a catcher acquisition this offseason, the buying team seems to know what they’re getting. The selling team, in the instance of a trade, hasn’t seemed to care about what they’re giving up. Overall, the position seems to be quantified well enough by teams privately to get a deal they can easily appreciate, with the luxury of not having to prioritize such knowledge.

It’s possible that catcher compensation hasn’t quite matched the way front offices quantify the position’s value yet, even given the suppression of the current market, because the public sphere hasn’t quite broken open catcher analysis the way that we have with other positions. Public sabermetric work has fed front offices — the list is as impressive as it is long, hitting teams all over the league and including World Series rings.

The range of catchers on the move this winter, and the rate at which they’re changing uniforms, means that at least a few of them are bound to impact the standings somehow this summer. Just take a look for yourself:

That’s 11 catchers who carry some sort of positive significance through the majors. Seven have joined their new teams as free agents, with the other four have been traded. Three other catchers have signed big league deals and will likely see the weak side of a platoon but still get considerable playing time. The only other position-player group which has signed more free agent deals this winter are outfielders (12), and that total combines all three positions.

Simply put, catchers have been in demand despite the general free-agent market malaise affecting most of their colleagues. And part of that may be because of the value teams know they provide compared to what the public does, provided a lower cost.

Given that, let’s consider catchers in four ways.

The Total Package

Of the 11 catchers who have changed teams this winter, only two of them stand out as clearly above-average by both offensive and defensive standards: Yasmani Grandal and Yan Gomes.

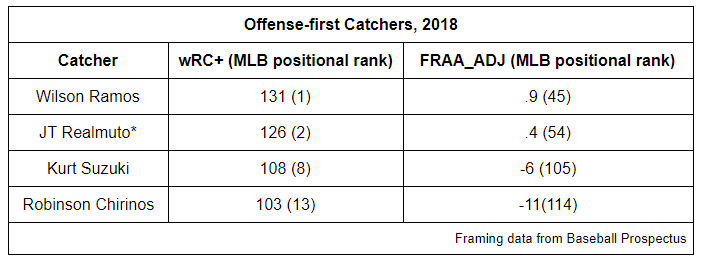

The two numbers in the chart above represent the crux of production for catchers when they’re at the plate (wRC+) and when they’re behind it (FRAA_ADJ, or Adjusted Framing Runs Above Average).

Grandal’s offensive output last year was topped only by J.T. Realmuto of the Marlins (now of the Phillies) and Wilson Ramos of the Rays and Phillies. Additionally, no one framed better than Grandal, and yet his contract guarantees him only $18.25 million on a one-year deal. While that accounts for nearly a quarter of all catcher money guaranteed this offseason on the open market, it’s also less than 30% of what MLBTR projected him to earn. Depending on your preferred metrics, Grandal was worth at least 1.3 wins more than what all Milwaukee catchers produced last year. Adding him to that roster for a year is a boon.

Gomes, meanwhile, was still 17% better with the stick than the average MLB catcher in 2018, and he saved nearly nine runs more than average behind the plate. Adding him could boost offensive production from the position for Washington by nearly 30% while also providing a top pitch-framer. That should help maintain the breaking balls of newly acquired ace Patrick Corbin as well as the rest of the team’s dynamic staff. The benefits may be bountiful.

What would the market pay for a position player who’s at least 17% better than league average at creating runs and has plus defense? We don’t really know. Many of those players — Mookie Betts, Didi Gregorius, Andrelton Simmons — either haven’t yet reached free agency or guaranteed themselves what was a decent payday for security’s sake before they went through the attrition of arbitration. The closest examples we might have are Jean Segura, who signed a five-year, $70 million deal with Seattle before reaching the open market that was seen as team-friendly, and Lorenzo Cain, who signed a five-year deal worth $80 million in free agency last winter as he was going into his age-32 season.

Depressed market or not, this is perhaps where those teams who went fishing in the deep end of the catching talent pool lucked out. While Grandal reportedly turned down a four-year offer worth between $50 and $55 million from the Mets, we can’t guarantee that. And either way, the average annual value of such a deal would’ve been worth less than even Segura’s pact. Gomes may not have been a free-agent acquisition, but he was effectively pared by Cleveland for two lottery tickets in 25-year-old, lower-pedigree starter Jefry Rodriguez and 23-year-old Daniel Johnson, who projects as a platoon player. Gomes will make only $7 million in 2019 as part of a six-year deal he signed in 2014, in a contract designed like Simmons’ — to give a good, young player an amount of money that provided them with a level of security that was hardly certain before.

Beyond Grandal and Gomes, teams have had to decide whether they’d value offense or defense more from their catchers. That moves us onto the next look the catching market has gotten.

The Offense-First Catchers

Realmuto represents the wild card here. When the Phillies acquired him, GM Matt Klentak called him the best catcher in baseball. Perhaps surprisingly, the numbers on which this piece focus don’t exactly bear that out, but it’s well-documented that Marlins Park has tanked his numbers at home. Over the last three years, his wRC+ at home is 48 points lower there than on the road. He’s succeeded despite playing half his games in an environment that suppresses his production, so moving to the more hospitable Citizens Bank Park is a huge plus.

As for his framing, the Phillies were 12th in the league last year after being dead last in 2017. They committed to a completely new, diverse, and comprehensive approach to their defense behind the plate. Per Matt Gelb of The Athletic, Realmuto’s already learned aspects of his game he can get better at, and it’s fair to bake in improvement there just like it is for his hitting.

The other three players above account for $34.5 million, or nearly 46% of catcher guarantees on the open market so far this offseason. Ramos is so good with the bat that if he were even a few runs better behind the plate, he’d be in that esteemed grouping with Grandal and Gomes. But he isn’t, and he signed a deal with the Mets that carries an AAV of $9.5 million over two years. His offense last year was better than what Mets catchers produced by more than 50%. His receiving skills behind the plate probably won’t offend anyone moving forward. The team is probably perfectly content, if not ecstatic, to pay less than half of what they reportedly offered to Grandal and get more than half the production.

Suzuki will represent the other half of a platoon with Gomes in Washington, where the team clearly wanted to upgrade their average offense after putting up a 64 wRC+ from the position last year. Their catchers are now a serious threat in their lineup, relatively speaking.

Houston’s signing of Robinson Chirinos comes with the curiosity of how his power will perform with the short porch in left field at home in Minute Maid Park. They’re not losing any veteran leadership compared to the erstwhile Brian McCann — Chirinos is 34 — and they’re gaining a roughly 20% increase in runs created from the position.

The best free agent comp for any of this trio may be J.D. Martinez last winter. His offense is unquestionable, as he sports a wRC+ of 154 since 2014. However, his defense may be equally bad. After waiting around like sixth graders at a school dance, he and the Red Sox agreed to a five-year, $110 million deal last winter with three player opt-outs, stipulations that generally benefit the player and not the team. Though a superior hitter relative to his own positional peers compared to these three catchers and theirs, Martinez’s overall value doesn’t appear to be miles ahead of them. That said, he’s still taking home a far larger guarantee.

The Defense-First Catchers

Jeff Mathis is a fascinating baseball player. He ranks 577th in wRC+ among the 585 qualified catchers in all of baseball history. He’s historically lousy at the plate. But he’s really, really good behind it; good enough to have kept him in the Majors for more than a decade. Google “Jeff Mathis framing” and you’ll be enamored by the words that have been poured out expounding his talents for calling a game. He’ll earn $6.25 million over two years.

The Rangers are rebuilding. They’ll be taking a chance on a lot of guys, both young and previously established. Three-fifths of their current projected rotation — Edinson Volquez, Drew Smyly, and Shelby Miller — are coming off Tommy John surgery. They need the help on defense more than offense. Mathis is a certain relief for the bevy of arms who will work through the Texas roster in the two years he’s contracted. A good comp for him among other position players may be Miguel Rojas, a glove-first shortstop who will earn $3.15 million in 2019. Even then, however, that’s through arbitration and not on the free market.

Alfaro may have been technically above-average at the plate last year by wRC+, but that’s buoyed by a white-hot September that saw him post a 186 wRC+. Behind the plate, he was a beneficiary of Philly’s revamped approach — he was 83rd among all catcher the year before — and he may be able to take those new skills to Miami. He’s also still only 25. But he’s also been known for his loud tools since he was a teenager, and they’ve never quite clicked in a way that will make him a star, as he’s dogged by a swing-happy approach.

Martin, like Gomes, was acquired via trade. He’s in the final year of a five-year, $82 million, back-loaded contract he signed as a free agent. He’ll earn $20 million in 2019 (though the Dodgers will pay only $3.6 million) and play this coming season at age 36. Martin hasn’t played more than 91 games in the last two years and is clearly in the twilight of his career, and he will be more of another steady piece to cycle in for the Dodgers than a singular solution. There was a time when he was one of the best all-around catchers in the game, much like Grandal and Gomes currently are, which helped him land his current contract.

That deal could be considered as both a warning for teams thinking about signing a catcher to a long-term contract who’s already 30 as well as what the market is currently willing to pay for a player with such skills on a one-year deal. But given the dearth of other examples, and Martin having already accrued nearly 12 WARP over the life of the contract, it’s fairly easy to justify the money he’s received. His peers aren’t getting that kind of deal at this point though, suggesting a possible over-correction in valuation on the position as the game cares less about defense.

The Leftovers

These two are like Martin in that they’re far from what they once were. McCann has gone back to Atlanta, where the team likely hopes he’ll provide stability for a young core in a similar way to how he did for Houston when they won the World Series in 2017. It also doesn’t hurt that they’ve got a prospect like William Contreras, who currently grades out as a regular, working through the minors. A one-year stop-gap in McCann makes plenty of sense.

Lucroy’s descent has been more drastic than McCann’s. The Angels will pay him nearly as much as the Dodgers will pay Martin, but for roughly three-fourths of the projected productivity. The team has made a habit of short-term bets like this in the last few years. Just this offseason, they’ve added Matt Harvey, Justin Bour, and Cody Allen on similar contracts. They won’t lose much if Lucroy doesn’t pay off.

The clubs handing out contracts to these players are getting exactly what they want: a palatable package with name value and veteran presence for nearly the minimum commitment. It’s interesting, however, that Lucroy will make more on his one-year deal than Mathis will per year in Texas while seemingly not offering a high-level skill anymore.

The Reality of the Catcher Market

Baseball is in an odd place. We’ve got multiple years left in a CBA that’s already wringing the earnings of players at what are largely unprecedented levels. Nearly no one is getting signed, as evidenced by the 100-plus remaining free agents of massively varying talent.

And here are catchers, moving at a rate that suggests clubs have a very specific intent for and mindset about them, while still not paying them like they’re a priority. They almost appear fungible. But when all is said and done in 2019, the win column may well say otherwise.

—

Framing data and WARP from Baseball Prospectus. Contract data from Spotrac. All other data from FanGraphs.

A previous version of this piece first appeared on Tim’s site on 01/30/18.

Tim Jackson is a writer and educator who loves pitching duels. Find him and all his baseball thoughts online at timjacksonwrites.com/baseball and @TimCertain.

This is the best piece I’ve ever read on Fangraphs Community (and I read them all). Hey, Meg. Hey, Appelman. This is the guy to hire.

Why in the world are you judging catcher defense purely from framing?! Blocking and throwing are still big parts of catcher defense, you know.

I know that the all-inclusive metrics have a hard time accurately representing catcher defense (even more so than other positions’ defense), but they’re still a lot better than just purposely ignoring a huge chunk of the job.

Not using other stats isn’t an indication that I don’t think they’re important. FRAA_ADJ is the only isolated, league-adjusted stat for catcher defense I’m aware of in the public sphere, and it’s still behind a pay wall. If you know of others, I’d love to hear about them.

Thanks for reading!