Brandon Inge, Superstar.

How many wins is chemistry worth? Do nice guys really finish last?

As a Pirates fan since birth, I’ve grown used to my baseball fandom engendering a sense of sympathy in others. Born in 1989, I came of baseball-loving age in the mid-nineties, immediately following the halcyon Bonds/Bonilla/Van Slyke & co. days and immediately preceding the less-halcyon days of the Aramis Ramirez-for-Bobby Hill trade, “Operation Shutdown,” the expansion-drafting of Joe Randa, Pat Meares’ general existence, the Moskos pick, the Matt Morris trade . . . (list of soul-crushingly depressing baseball stories truncated for reader’s mental health).

And yet I remained faithful, despite having no conscious memory of a Pirates team being anything other than heartbreakingly awful. I’ve since likened this experience, in conversations with friends, to Linus sitting in the pumpkin patch each year, waiting for the Great Pumpkin to appear. It sometimes seemed that the Great Pumpkin would never come.

It’s ironic, then, that in the year that finally saw the Great Pumpkin arrive in Pittsburgh (2013), the same city also witnessed the end of the career of one Charles Brandon Inge.

Inge, nicknamed ‘Cringe’ by some of the crueler Pittsburgh faithful for his anemic .181/.204/.238 batting line during the 2013 campaign, was at that point in his thirteenth season as one of baseball’s premiere utility men, playing every position on the diamond during his career. During his peak, he was a slick-fielding third baseman who also clubbed 27 HRs en route to a 4.1 fWAR season in 2006. But by 2013, Inge was 36 and on his way out of the league. Signed before the season to provide depth behind Pedro Alvarez and Neil Walker, Inge’s poor performance eventually led to his unceremonious release by the Pirates at the end of July.

And yet, this article has less to do with Inge’s on-field merits (which, as the previous paragraph suggests, were both significant and significantly variable), and more to do with Inge’s impact off the field. Inge won the 2010 Marvin Miller Man of the Year Award, given to the player whose “performance and contributions to his community inspire others to higher levels of achievement,” for his work with C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital. A frequent visitor to C.S. Mott, Inge also donated $100,000 for a new infusion center to treat pediatric cancer and twice hit home runs for young cancer patients. Dude’s a nice guy.

Perhaps more relevant, though, is pitcher and noted stathead Brandon McCarthy’s statement that Inge and fellow veteran Jonny Gomes had been worth twenty-four wins to the 2012 Athletics through chemistry alone. Normative ethics aside, it’s impossible to measure the moral character of a man—but we can measure, or at least attempt to quantify, the impact he has on his teammates.

Intrigued, I set out to determine whether Inge, patron saint of chemistry and all-around good guy, really made such a gigantic difference to his teammates’ performance. Mine is not the first investigation into this topic—Baseball Prospectus’ Russell A. Carleton examined the same issue in March of 2013, and there have been numerous attempts to place a valuation on chemistry over the years. But as you’ll see, there are some methodological differences to our approaches, and the differences expose some interesting conclusions.

Methodology

There is no ironclad way to assess Inge’s potential effect on his teammates, short of cloning entire teams of players, randomly assigning Brandon Inges to some of them, and having them play a large number of seasons.

In order to determine Inge’s value as accurately as possible, I can’t simply measure his teammates’ performance—I’d just be concluding that Inge played with good or bad teammates. Instead, I need to develop a counterfactual, or a method of estimating how we could’ve reasonably expected Inge’s teammates to play in his absence. Fortunately, an excellent one already exists—a ZiPS projection. ZiPS, to my knowledge, does not have a ‘played with Brandon Inge variable,’ so it should be unbiased. Carleton instead used an AR(1) covariance matrix to try to adjust for player talent, but given that ZiPS explicitly incorporates past performance with a view to projecting, as accurately as possible, how a player will perform in the upcoming season, I believe it is a suitable tool.

I chose wOBA as the dependent variable for our study—while Carleton looked at multiple indicators (BB%, K%, etc), one, all-encompassing measure of players’ offensive performance seems best suited to answering the question, “Do players perform better with Brandon Inge on their team?”

In order to develop the requisite dataset for this analysis, I downloaded every player-season since 2006[1] from FanGraphs’ leaderboards and filtered the data to include only those players who amassed at least 200 plate appearances. This yielded 3130 player-seasons. Next, I created a binary variable called ‘IngeTeammate,’ with a value of ‘1’ if the player was on Inge’s team during the given season (and not Inge himself), and ‘0’ if he wasn’t. For the 2012 season, the only one in which Inge played for multiple teams, I counted Inge as having played for the Athletics, with whom he spent the majority of the season.

The next part was a bit tricky—bringing in the ZiPS projections. The latest years, the ones for which ZiPS has been featured on FG, were easy—data was readily available, wOBA already calculated, and records already associated with a player id. But wading deeper into the past unearthed some issues—in order to match records, I had to manually match player names (including the two Chris Carters, and, apparently, two Abraham Nunezes . . . Nunezii . . . who knows?) and hand-calculate ZiPS-projected wOBA for older player-seasons using the weights provided on the FanGraphs Guts page. One potential issue with some of the oldest data is the lack of projections for things like intentional walks and sacrifice flies.

However, forging through all of the record-matching and manual wOBA-calculating eventually yielded ZiPS wOBA projections matched to 3088 of the 3130 player-seasons. Of the 42 unmatched seasons, only one was an Inge teammate (2010 Brennan Boesch). 81 of the 3088 matched seasons were Inge teammates. So unless you think ZiPS would have pegged Boesch, a relatively unknown 25-year-old at the time, for a significantly better performance than the .322 wOBA he posted in 2010, the unmatched records probably didn’t have a huge effect.

What we’re left with is data that look like this:

| Year |

Name |

Team |

Age |

PA |

IngeTeammate |

ZiPS wOBA |

wOBAdiff |

wOBA |

| 2010 |

Jose Bautista |

Blue Jays |

29 |

683 |

0 |

0.322 |

0.100 |

0.422 |

| 2010 |

Jim Thome |

Twins |

39 |

340 |

0 |

0.343 |

0.096 |

0.439 |

| 2010 |

Wilson Betemit |

Royals |

28 |

315 |

0 |

0.302 |

0.084 |

0.386 |

| 2010 |

Josh Hamilton |

Rangers |

29 |

571 |

0 |

0.365 |

0.080 |

0.445 |

| 2010 |

Chris Johnson |

Astros |

25 |

362 |

0 |

0.286 |

0.067 |

0.353 |

| 2010 |

Carlos Gonzalez |

Rockies |

24 |

636 |

0 |

0.350 |

0.063 |

0.413 |

| 2010 |

Justin Morneau |

Twins |

29 |

348 |

0 |

0.387 |

0.061 |

0.448 |

| 2010 |

Paul Konerko |

White Sox |

34 |

631 |

0 |

0.361 |

0.056 |

0.417 |

| 2010 |

Joey Votto |

Reds |

26 |

648 |

0 |

0.383 |

0.055 |

0.438 |

| 2010 |

Danny Valencia |

Twins |

25 |

322 |

0 |

0.299 |

0.052 |

0.351 |

| 2010 |

Giancarlo Stanton |

Marlins |

20 |

396 |

0 |

0.305 |

0.051 |

0.356 |

| 2010 |

Miguel Cairo |

Reds |

36 |

226 |

0 |

0.288 |

0.051 |

0.339 |

| 2010 |

Will Rhymes |

Tigers |

27 |

213 |

1 |

0.288 |

0.050 |

0.338 |

| 2010 |

Tyler Colvin |

Cubs |

24 |

395 |

0 |

0.301 |

0.050 |

0.351 |

| 2010 |

Michael Morse |

Nationals |

28 |

293 |

0 |

0.328 |

0.049 |

0.377 |

| 2010 |

Adrian Beltre |

Red Sox |

31 |

641 |

0 |

0.343 |

0.048 |

0.391 |

| 2010 |

Ryan Hanigan |

Reds |

29 |

243 |

0 |

0.321 |

0.048 |

0.369 |

| 2010 |

Yorvit Torrealba |

Padres |

31 |

363 |

0 |

0.279 |

0.044 |

0.323 |

| 2010 |

Matt Joyce |

Rays |

25 |

261 |

0 |

0.321 |

0.043 |

0.364 |

| 2010 |

Aubrey Huff |

Giants |

33 |

668 |

0 |

0.344 |

0.043 |

0.387 |

| 2010 |

Drew Stubbs |

Reds |

25 |

583 |

0 |

0.295 |

0.043 |

0.338 |

| 2010 |

Andres Torres |

Giants |

32 |

570 |

0 |

0.316 |

0.042 |

0.358 |

| 2010 |

Corey Patterson |

Orioles |

30 |

341 |

0 |

0.274 |

0.042 |

0.316 |

| 2010 |

Austin Jackson |

Tigers |

23 |

675 |

1 |

0.288 |

0.041 |

0.329 |

| 2010 |

Brett Gardner |

Yankees |

26 |

569 |

0 |

0.306 |

0.040 |

0.346 |

| 2010 |

Colby Rasmus |

Cardinals |

23 |

534 |

0 |

0.329 |

0.040 |

0.369 |

| 2010 |

Andruw Jones |

White Sox |

33 |

328 |

0 |

0.323 |

0.039 |

0.362 |

In the above table, wOBAdiff refers to the amount by which the player outperformed his ZiPS wOBA projection. A negative number would indicate that a player underperformed his projection. So Jose Bautista outperformed his 2010 projection by .100—multiplying by 1000 tells us that this was 100 points of wOBA. It was good to be Joey Bats in 2010.

Results

If we look at the mean wOBA deviation (in terms of points of wOBA) Inge teammates and non-teammates experienced from their ZiPS projections, we see the following results:

| |

Player-Seasons |

Total PA |

Mean Weighted Diff. (wOBA pts)

|

Mean Unweighted Diff. (wOBA pts)

|

| Non-Teammate |

3007 |

1,378,732 |

-3.09 |

-4.62 |

| Teammate |

81 |

37,965 |

4.30 |

4.24 |

In other words, if we weight by plate appearances, Inge teammates outperformed their ZiPS projections by an average of about 4.30 points of wOBA. All other players underperformed their projections by an average of about 3.09 points. Which might not seem like a lot, but if you were to apply that 7.4 wOBA difference to an average-hitting team over a 6000 PA team-season, that’s roughly 34 runs. So 3.4 wins. Which is, you know, quite a bit. The unweighted version is even more extreme, suggesting that players with lower numbers of PA have outperformed their projections even more when teamed with Inge.

If we simply run a regression including the independent variables IngeTeammate (binary) and age and the dependent variable wOBAdiff (unweighted), we can express the story another way:

wOBAdiff = 0.0127064 + (IngeTeammate* 0.0090544) + (age* -0.0005993)

I included age as a control because ZiPS projections, as you can see from the model above, tended to slightly overproject older players in comparison to younger players, and therefore I needed to consider the possibility that Inge simply benefitted from playing only with young players (he didn’t).

Note that in the model above, 0.001 corresponds to one point of wOBA (i.e. a hitter moving from .323 to .324 would have gained a point of wOBA). The r-squared of the model is absurdly low (0.006), but that’s to be expected—after all, I’m not trying to assert that Brandon Inge is responsible for all or even a significant part of the variation between MLB players’ expected and actual performance. More importantly, the variable ‘IngeTeammate’ is significant at a 98.4% threshold.

Considering the possible influence of aging is interesting, as the Inge difference is even more pronounced among younger players, or those whom he allegedly mentored while playing with the A’s. If we filter the data above to include only players 27 and younger, the table looks like this:

| |

Player-Seasons |

Total PA |

Mean Weighted Diff. (wOBA pts)

|

Mean Unweighted Diff. (wOBA pts)

|

| Non-Teammate |

1241 |

568,944 |

-0.50 |

-2.09 |

| Teammate |

30 |

14,298 |

16.58 |

17.27 |

We’re starting to run into some serious sample size issues that make me uncomfortable drawing any particularly bold conclusions, but young players who play with Inge have done really, really well, collectively knocking the snot out of their ZiPS projections. There are problems with extrapolating this to a 6000 PA team-season, given that presumably an entire team won’t be composed of young players, but if one did so the result would be a ridiculous 78.6 runs of additional value.

The table below lists every 27-and-under player season for which the player was an Inge teammate:

| Year |

Name |

Team |

Age |

PA |

ZiPSwOBA |

wOBAdiff |

wOBA |

| 2008 |

Matt Joyce |

Tigers |

23 |

277 |

0.275 |

0.084 |

0.359 |

| 2011 |

Alex Avila |

Tigers |

24 |

551 |

0.308 |

0.076 |

0.384 |

| 2013 |

Jordy Mercer |

Pirates |

26 |

365 |

0.282 |

0.051 |

0.333 |

| 2010 |

Will Rhymes |

Tigers |

27 |

213 |

0.288 |

0.050 |

0.338 |

| 2012 |

Chris Carter |

Athletics |

25 |

260 |

0.319 |

0.050 |

0.369 |

| 2011 |

Brennan Boesch |

Tigers |

26 |

472 |

0.300 |

0.048 |

0.348 |

| 2007 |

Curtis Granderson |

Tigers |

26 |

676 |

0.344 |

0.044 |

0.388 |

| 2010 |

Austin Jackson |

Tigers |

23 |

675 |

0.288 |

0.041 |

0.329 |

| 2012 |

Yoenis Cespedes |

Athletics |

26 |

540 |

0.328 |

0.040 |

0.368 |

| 2010 |

Miguel Cabrera |

Tigers |

27 |

648 |

0.399 |

0.032 |

0.431 |

| 2013 |

Jose Tabata |

Pirates |

24 |

341 |

0.308 |

0.032 |

0.340 |

| 2012 |

Josh Reddick |

Athletics |

25 |

673 |

0.296 |

0.030 |

0.326 |

| 2013 |

Andrew McCutchen |

Pirates |

26 |

674 |

0.365 |

0.028 |

0.393 |

| 2013 |

Starling Marte |

Pirates |

24 |

566 |

0.317 |

0.027 |

0.344 |

| 2006 |

Omar Infante |

Tigers |

24 |

245 |

0.306 |

0.016 |

0.322 |

| 2008 |

Curtis Granderson |

Tigers |

27 |

629 |

0.358 |

0.015 |

0.373 |

| 2009 |

Clete Thomas |

Tigers |

25 |

310 |

0.302 |

0.015 |

0.317 |

| 2012 |

Josh Donaldson |

Athletics |

26 |

294 |

0.286 |

0.014 |

0.300 |

| 2011 |

Andy Dirks |

Tigers |

25 |

235 |

0.297 |

0.011 |

0.308 |

| 2013 |

Neil Walker |

Pirates |

27 |

551 |

0.328 |

0.005 |

0.333 |

| 2013 |

Pedro Alvarez |

Pirates |

26 |

614 |

0.327 |

0.003 |

0.330 |

| 2006 |

Curtis Granderson |

Tigers |

25 |

679 |

0.335 |

0.000 |

0.335 |

| 2009 |

Miguel Cabrera |

Tigers |

26 |

685 |

0.407 |

-0.005 |

0.402 |

| 2010 |

Alex Avila |

Tigers |

23 |

333 |

0.306 |

-0.007 |

0.299 |

| 2011 |

Austin Jackson |

Tigers |

24 |

668 |

0.315 |

-0.010 |

0.305 |

| 2012 |

Jemile Weeks |

Athletics |

25 |

511 |

0.304 |

-0.028 |

0.276 |

| 2012 |

Derek Norris |

Athletics |

23 |

232 |

0.304 |

-0.029 |

0.275 |

| 2006 |

Chris Shelton |

Tigers |

26 |

412 |

0.380 |

-0.033 |

0.347 |

| 2013 |

Travis Snider |

Pirates |

25 |

285 |

0.310 |

-0.039 |

0.271 |

| 2008 |

Miguel Cabrera |

Tigers |

25 |

684 |

0.419 |

-0.043 |

0.376 |

It’s not as if one year is hugely skewing the results—pretty much every year, whichever young players happen to be playing with Brandon Inge outperform their projections. The graph below illustrates the mean wOBA differential younger Inge teammates exhibited each season. I would’ve imagined, prior to viewing these results, that Inge’s positive ‘effect’ might’ve been almost entirely a product of the 2012 Athletics, but this doesn’t seem to be the case—outside of the 2006 Tigers (when Omar Infante, Curtis Granderson, and Chris Shelton collectively underperformed their ZiPS projections by a modest average of ~5 points of wOBA), Inge’s younger teammates have outperformed ZiPS every single year in the sample.

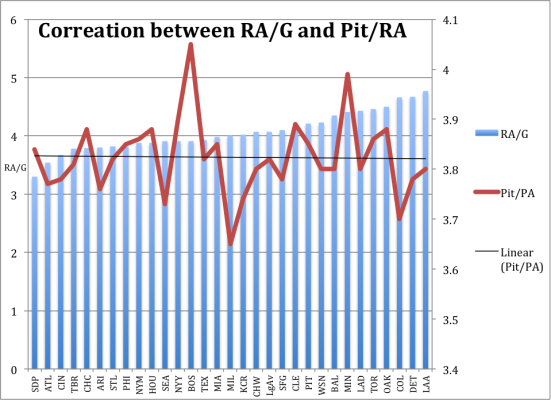

Perhaps, one could say, Inge has simply benefitted from playing on teams run by intelligent front offices. After all, the Tigers, Athletics, and (more recently) the Pirates all have reputations as relatively savvy management teams. Maybe they’re just collectively able to out-forecast ZiPS.

When we look at ZiPS wOBA differentials by team, however, the Tigers (+1.36 points of wOBA), Athletics (+0.11) and Pirates (-0.31) all had weighted mean differentials less than the Inge gap. The average over all teams was -2.89, so while all three front offices ‘beat the market,’ so to speak, they still don’t explain the huge Inge effect. It looks as though there’s something here.

After observing the results for Inge, I was curious about whether other veteran players might also exhibit similar correlations—while we’d expect to find no correlation with ZiPS wOBA differential for most players, it might be the case that, as with Inge, patterns emerge. Specifically, I looked at two players with diametrically opposite reputations—A.J. Pierzynski and Jonny Gomes. Below, I replicate the initial summary table used for the Inge analysis and note the magnitude of the effect:

A.J. Pierzynski

| |

Player-Seasons |

Total PA |

Mean Weighted Diff. (wOBA pts)

|

Mean Unweighted Diff. (wOBA pts)

|

| Non-Teammate |

3004 |

1,375,450 |

-2.75 |

-4.29 |

| Teammate |

84 |

41,247 |

-7.65 |

-7.87 |

The game’s most hated player didn’t fail to disappoint, as his teammates collectively underperformed their ZiPS projections by an additional of 4.9 points of wOBA when compared to non-teammates, an effect worth -22.6 runs to the team over the course of a full season. I should note that I assigned Pierzynski to the 2014 Red Sox (with whom he spent considerably more time) instead of the 2014 Cardinals—both teams underperformed their ZiPS projections, but the Red Sox did so by a larger margin.

Pierzynski’s unweighted results, while still negative, are less damning, and using a regressed model reflects this:

wOBAdiff = 0.0128794+ (AJTeammate* -0.0033689) + (age* -0.0005939)

The intercept and coefficient for age are, understandably, almost identical to those I observed in the Inge model. The significance level for AJTeammate, however, is only 64.1%, suggesting that we can’t really conclude much of anything with the same level of confidence as for Inge.

Still, twenty-plus runs is a non-negligible amount, and Pierzynski’s numbers have been negative across all four teams for whom he’s played (White Sox, Rangers, Red Sox, Cardinals). It may be that more historical data would reveal a broader trend, given that we’ve limited our sample size to only the latter half of Pierzynski’s career.

Jonny Gomes

| |

Player-Seasons |

Total PA |

Mean Weighted Diff. (wOBA pts)

|

Mean Unweighted Diff. (wOBA pts)

|

| Non-Teammate |

3000 |

1,376,613 |

-3.05 |

-4.56 |

| Teammate |

88 |

40,084 |

2.58 |

1.52 |

The phenomenally-bearded Gomes, Inge’s running partner in the Brandon McCarthy quote that triggered this analysis, also appears to be a potential chemistry star, though his results are less extreme than Inge’s. His teammates outperformed non-teammates by 5.6 points of wOBA, worth an estimated 26 runs per season.

wOBAdiff = 0.0124387+ (GomesTeammate* 0.0055032) + (age* -0.0005873)

The effect, as with Pierzynski, is not statistically significant—the significance level is 87.4%.

Conclusions

We can’t make firm statements about causality from this analysis, but we can say pretty conclusively that being on the same team as Inge during the last nine years correlates positively with hitting better than ZiPS projects you to hit.

Maybe you don’t believe Inge should get credit for the extra 3.4 wins of value each year. We don’t have a ‘chemistry above replacement’ metric to account for the fact that some other player with a modicum of veteranosity might plausibly have a positive effect if analyzed the same way. And there’s no feasible way to develop one on the horizon—you can only start to do this sort of analysis retrospectively, and it requires a large number of plate appearances and player-seasons before we can conclude that any pattern has emerged. I’m not really arguing that Inge deserves all the credit for his teammates’ overperformance, only that we have reason to believe a nonzero effect may exist.

But let’s entertain, for a minute, the possibility that the 3.4 win-per-season gap we see *is* entirely attributable to Inge. That maybe all the minute, unnoticed interactions between players over the course of a season can add up to improved performance at the plate. The effect could even be greater than 3.4 wins—I didn’t examine pitching and fielding at all. After all, everything we know about human psychology suggests that happier workers are more productive, and I’ve yet to hear any compelling reason that ballplayers constitute an exception. We sometimes, in the analytics community, fall into the trap of assuming that because we can’t measure something accurately, it doesn’t deserve a meaningful place in our analysis. And yet our inability to measure a phenomenon is not proof of its nonexistence—just ten years ago, we lacked meaningful metrics for catcher framing, for instance.

Perhaps Inge contributed more hidden value over the last decade than anyone this side of Jose Molina, and Brandon McCarthy’s twenty-four wins were, if still hyperbole, grounded in a subtle truth. 3.4 wins currently has a market value north of $20M, making Inge a substantially underpaid man over the course of his career.

It’s a shame, on some level, that it’s only after he’s retired that we recognize the unheralded Inge for who he might secretly have been: Brandon Inge, Superstar.

[1] Before 2006, I struggled to find ZiPS projections in a readable format to develop the counterfactuals.

Data retrieved from FanGraphs and Baseball Think Factory.