Speculating the 2016 Toronto Blue Jays Lineup

We’re halfway through November and the winter meetings are right around the corner. Teams are gearing up for next year and taking a look at their rosters, deciding what direction they want their team to head. Today I want to look at the Toronto Blue Jays and hypothesize a direction they could go.

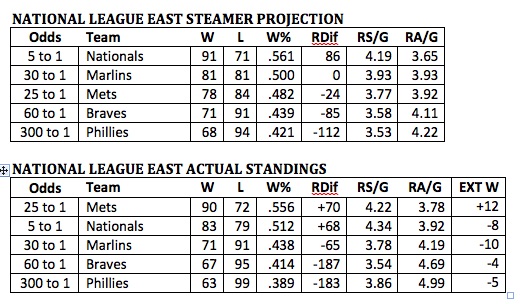

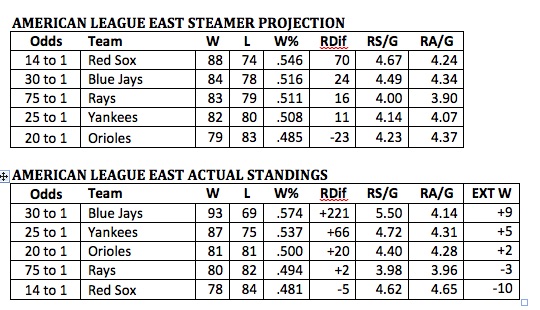

The Blue Jays had a great 2015 and continuing that momentum is crucial for the newly recharged fan base. They have a number of quality young players who contributed this past year. Kevin Pillar, Chris Colabello, Ryan Goins, Marcus Stroman, Roberto Osuna and Devon Travis (when healthy) all had nice seasons and remain under team control in some shape or form for the next 3-5 years. The Jays also have some large expiring contracts after the 2016 season in the form of R.A. Dickey, Edwin Encarnacion and Jose Bautista who have been important pieces to Toronto’s success. Add in Russell Martin, Josh Donaldson and Troy Tulowitzki and the Blue Jays should once again compete in the AL East in 2016. One of the glaring issues however is their starting rotation and bullpen.

With Marco Estrada signed the Blue Jays have a starting rotation of Dickey, Stroman, Estrada and Hutchison. Reports have come out and the Jays will reportedly have a similar budget to last year, around $140 million. After the guaranteed contracts, arbitration estimates and league-minimum salaries are accounted for the Blue Jays will have about $18-$19 million to spend on starting pitching and bullpen help. There are a number of directions the Blue Jays could go; it’s a solid class of starting pitching this year and with the $18 million left in the salary they could for sure pick up a quality starting pitcher to fill out the rotation. They could also spent the money on a lockdown relief pitcher and try to transition either Aaron Sanchez or Roberto Osuna to the rotation. Or they could split up the money and get an older starting pitcher and get whatever reliever is available for the remainder of the money. Another option, and the one that I’m going to explore, is the trade route.

With all the moves the Blue Jays made at the deadline, their farm system isn’t as strong as it was at midseason last year but the recent developments with the Atlanta Braves got me thinking about trade ideas — mainly Julio Teheran. With the Braves set to open a new stadium in 2017 the mentality has been to shed money and stock prospects for the opening season in the new stadium. This works out great for the Blue Jays who have some talent left in the farm system that could be useful to the Braves. The fourth-ranked prospect in the Blue Jays system and coincidentally the fourth-ranked catching prospect in baseball is Max Pentecost. Atlanta has been stocking arms in recent trades but with Christian Bethancourt struggling in his time in the majors, the Braves clearly don’t have a long-term solution behind the dish. The former 1st round pick, 11th overall is currently in advanced-A ball and his estimated time of arrival in the majors is 2017, perfect for their rebuilding plans. If the Jays were to include one maybe two young pitchers on a similar timeline like Conner Greene and/or Marcus Smoral, perhaps that would be enough to pluck Teheran away from Atlanta.

Teheran is only 24 years old and will turn 25 for the 2016 season. He’s owed a bargain-basement price of $3,466,666 for next season, is under contract through 2019, and has a club option for 2020. With starting pitcher salaries estimated anywhere from $10-$25 million and up this offseason, Teheran and his $3.5 million in 2016 season seem like a steal. Plus the Blue Jays would be getting Teheran for the prime years of his career and although last year was an off year, he’s shown signs of being an ace. Teheran would complete the starting rotation for the Jays in 2016 and after Dickey’s contract expires, Toronto would be left with a rotation of Stroman, Teheran, Hutchison and Estrada for the 2017 season. The other nice thing about Teheran is that his $3.5 million contract leaves Toronto with roughly $15.5 million left over to fill out the bullpen or upgrade other areas. Teheran would be an affordable and valuable piece to a rotation that desperately needs it and would be far better then spending 3 to 4 times his annual 2016 salary on a pitcher that may already be or not far away from the decline of his career.

As I mentioned above, with the money saved on the Teheran trade, the Blue Jays could add a piece to the bullpen or upgrade other areas but in compiling data for this article, I got to thinking about what the Jays could do for the future. 2017 has roughly $36 million coming off the books for Toronto and with a young core of controllable players, the Jays have some room to make a move. One of the contracts expiring is RF Jose Bautista. I personally think the Jays should re-sign Bautista after 2017 but I don’t think putting him in right would make sense. With Encarnacion’s contract set to expire as well, the DH spot would be available for Bautista, should he choose to stick around. That would leave RF empty and looking at the outfield class of 2017 (Beltran, Suzuki, Gregor Blanco, Josh Reddick, Brandon Moss, Mark Trumbo and of course Bautista) the group leaves something to be desired.

That brought me to the 2016 class, led by arguable the best right fielder in the game, Jason Heyward. The Jays have been rumored to be after SP free agents David Price and Zack Greinke but for the amount of money they’ll command and the stages they’re at in their career, I think the money might be better spent on a player whose best days are ahead of him. That in my opinion is Jason Heyward. We know Heyward is a solid player, who’s shown flashes of brilliance and is young enough to still put it all together consistently. In a lineup like the Blue Jays’, Heyward would thrive much the way Josh Donaldson officially broke out as a superstar last year. Heyward would have the protection and opportunities to truly develop into the player he’s about to get paid to be. The problem with signing Heyward would be the Blue Jays would have to free up a sizable amount of money and the only real place to look is at shortstop in the form of Troy Tulowitzki.

Tulowitzki was a surprise addition for the Blue Jays last year and definitely added strength to an already dangerous lineup but with the depth that Toronto has with Ryan Goins able to play SS and the return of Devon Travis, the 31-year-old Tulowitzki becomes an expensive option for the remainder of his career. Perhaps the Jays should trade Tulowitzki to free up money to sign Heyward to a long-term deal? Instead of watching the expensive decline of Tulo for the remainder of his contract, Toronto could still sell high to a team willing to take on the contract, receiving bullpen help and possibly an extra outfielder to help address current needs.

I then started going through MLB teams to see which ones would possibly be in a situation to make the trade happen. The Diamondbacks, White Sox and Mets all stood out as possible suitors while the Rangers, Yankees, Padres and Mariners also seemed like possible options. For the purposes of this article I’m only going to focus on the first three.

With a 2015 budget of about $76,622,575 million the Arizona Diamondbacks definitely have room to financially take on Tulo’s contract; the question is, is that where LaRussa and Dave Stewart want to take the team? None of us truly know but if the asking price is right, perhaps Randall Delgado and Ender Inciarte, maybe the thought of Tulo and Goldschmidt would fit their plans. They did spend $68.5 million for 6 years of Yasmany Tomas and with the emergence of David Peralta and A.J. Pollock, the Diamondbacks have outfielders to spare. If the trade were to go through the Blue Jays would gain about $18,487,000 giving them a total available amount of about $33,980,334. That would definitely be enough to sign Heyward to a 7-10 year deal (depending on what the market drives his year amount to) at anywhere from $20-$29 million per season. With the $36 million coming off the books in 2017, Toronto would have about $37 million to spend on the DH spot (Possibly Bautista) and SP or RP spot open (depending on how they handle Sanchez and Osuna). Compared to the $50 million amount they could have in 2017 minus whatever they pay for a starting pitcher this off season. In reality that $50 million would probably be more like $30-$35 million with two rotation spots available as well as the DH. If the Teheran trade and Heyward signing were to happen, here is what the 2016 and 2017 Blue Jays lineup would look like.

2016 Lineup 2017 Lineup

C = R. Martin C = R. Martin

1B = E. Encarnacion 1B = C. Colabello

2B = D. Travis 2B = D. Travis

3B = J. Donaldson 3B = J. Donaldson

SS = R. Goins SS = R. Goins

LF = B. Revere LF = B. Revere

CF = K. Pillar CF = K. Pillar

RF = J. Heyward RF = J. Heyward

DH = J. Bautista DH = ?

SP = R.A. Dickey SP = M. Stroman

SP = M. Stroman SP = J. Teheran

SP = J. Teheran SP = D. Hutchison

SP = D. Hutchison SP = M. Estrada

SP = M. Estrada SP = ?

RP = R. Osuna RP = R. Osuna

RP = A. Sanchez RP = A. Sanchez

RP = L. Hendricks RP = L. Hendricks

RP = B. Cecil RP = B. Cecil

RP = R. Delgado RP = R. Delgado

RP = S. Delabar RP = S. Delabar

RP = A. Loup RP = A. Loup

BN = E. Inciarte BN = E. Inciarte

BN = J. Thole BN = D. Pompey

BN = C. Colabello BN = ?

BN = D. Barney BN = ?

If Heyward’s contract was structured so that his first year was set at $20 million, the Jays would enter 2016 with about $13-$14 million left in the budget for any additional moves. It would also shore up right field a year before it’s an issue while upgrading the bullpen and perhaps leading the way for Sanchez or Ozuna to enter the rotation for 2017. The point is Toronto has money coming available next year but in order to get the player that best fits their future needs, they might have to make a move now instead of waiting till next year.

The next team I thought might make sense as a trade partner was the Chicago White Sox, who recently released long time SS, Alexi Ramirez. The White Sox had a budget of $118,860,487 in 2015 and were supposed to be contenders with the additions of Melky Cabrera, Jeff Samardzija, David Robertson and Adam LaRoche but instead fell way short and put together an all-around forgettable season. With the release of Ramirez, shortstop seems to be an area of need for Chicago, and Tulowitzki with Abreu, Cabrera and LaRoche would be a great fit on the south side.

Unlike the Diamondbacks however the White Sox don’t have as much potential new money available, so off-setting the cost of Tulo’s contract would have to be taken into account when thinking about a trade. Someone like Zach Duke, who is owed $5,000,000 over the next two years might be a good addition to the Toronto bullpen. If the Sox would somehow include often-injured Avisail Garcia, this trade might really swing in Toronto’s favor but really saving money for a Heyward run would be more important then any name on the back of a jersey.

For argument’s sake I’m going to use the Duke/Garcia for Tulowitzki trade as an example. The difference in salaries would be about $12.7 million and that added to the $15,493,334 left over after the Teheran trade, Toronto would have about $28,193,334 left over to make Heyward an offer. And again, if the contract was structured so that the first year paid Heyward $20 million, the Blue Jays would have about $8 million left over for additional offseason/mid-season upgrades.

The last team that I thought would make sense for a potential Tulo trade was a team that was linked to him while he was still in Colorado, the New York Mets. Coming off a spectacular run to the World Series, the Mets are set to lose Yoenis Cespedes and Daniel Murphy to free agency. In 2015 they had a payroll of $120,415,688 and Cespedes and Murphy combined for $11,729,508 of that total budget, over half of what Tulowitzki is owed going into 2016. For the Mets, their quality rotation is under team control or earlier arbititration for the next few years, so continuing the winning environment at a fraction of the cost is of utmost importance. The health of David Wright is suspect and with a nice young group in Conforto, d’Arnaud, Duda, and Lagares, trading for someone of Tulo’s caliber might help their development and continue the winning environment.

The Mets would be in the same situation that the White Sox are — they can’t add too much salary, so off-setting costs would play into the equation. If the Mets traded Jonathan Niese, who’s owed about $9 million in 2016, and Kirk Nieuwenhuis, they’d clear about $10,688,729. Add that with the money saved from letting Murphy and Cespedes walk and they could easily bring in Tulowitzki’s contract. The Blue Jays would have about $26 million to work with and again, if Heyward’s first year was set at $20 million, they’d have about $6,182,063 to work with for offseason/mid-season upgrades.

All of this is unauthorized speculation but I do think that the Blue Jays are in a unique situation where they can really make some moves that could set them up for years of success. Chasing the big-name starting pitchers may seem like the obvious move but taking advantage of other team’s situations could allow them to acquire elite talent for minimal cost and the money saved on starting pitching could be used to solve future needs that aren’t quite here yet. As always, thanks for reading and let me know what you think.

(pearlswithplaid, pearlswithplaid.blogspot.com)

(pearlswithplaid, pearlswithplaid.blogspot.com)