When learning the game of baseball, players are often taught about the importance of hitting the ball where it’s pitched. This means that, if the pitch is inside, it should be pulled, if it’s in the middle of the plate, it should be hit back up the middle, and if it’s outside, it should be driven to the opposite field. This is advice that generally makes intuitive sense. I’m sure we’ve all seen batters reach to pull an outside pitch and roll over it for a soft ground ball. We’ve also seen batters trying to fight off inside pitches and hit a weak ground ball or pop up to the opposite field.

However, the reemergence of the home run has led me to wonder just how valuable this guidance is. Over and over again, Bryce Harper has been able to extend on an outside pitch and deposit it into the right-field bleachers for a home run. Now, Bryce Harper is very often the exception to the rule, and an approach that works for him may not be suitable for 99% of the league. That being said, more and more home runs are being hit, and not very many of them are being hit to the opposite field. Based on Statcast data from Baseball Savant, in 2016 approximately 79% of home runs were hit to the pull side of the field. Therefore, maybe it does make sense to load up and try to pull everything with the hope of hitting for more power.

To further investigate this, all batted balls from 2016 were queried from Baseball Savant and analyzed. These batted balls were bucketed into four groups based on the pitch and batted-ball locations, separating each pitch as inside or outside (relative to the middle of home plate) and pulled or hit to the opposite field (using the middle of the field as the dividing line). A few offensive statistics for each group are shown in the following table.

Maybe it is a good idea to just pull everything after all. For both the inside and outside buckets, batters hit the ball harder and are more successful when pulling the ball. The results on outside pitches are relatively close. However, it is definitely not a good idea to try to hit inside pitches the other way. I don’t think any batters are intentionally doing this right now or this is something that would come as a shocking discovery, but the data shows that by far the most weakly hit balls are inside pitches hit the other way. I’d imagine a lot of these are scenarios where a batter gets jammed as opposed to trying to take the ball to the opposite field.

While it does appear that pulled balls are hit harder, the buckets here are pretty broad. Right now we’re grouping pitches a half inch away from the middle of the plate in the same group as pitches on the outside edge of the strike zone or outside the strike zone entirely. Therefore, it might be worth looking at the outside pitches further while using slightly more narrow buckets.

The table below shows pitch locations bucketed into two groups: slightly outside and way outside. To get these two groups, the plate was split into quartiles. Slightly outside pitches are located in the 3rd quartile when counting from inside out, while pitches further outside than the 3rd quartile were considered way outside. In other words, the dividing line was the midpoint of the outside half of the plate. As the table shows, the results aren’t as simple as saying that every pitch should be pulled for maximum effectiveness.

For pitches that are just barely outside, batters experienced much more success in 2016 by pulling the baseball. However for pitches that were well on the outer half of the plate or even further outside, hitting the ball to the opposite field is by far the better option. There are several key takeaways to note here. When looking at wOBA, the success of hitting to the opposite field does improve when the pitch is further away, but only slightly. However, the results of pulling the ball absolutely crater when moving from pitches that are just barely outside to way outside. It’s really hard to pull a ball that far outside with any authority. Those pitches are much more likely to result in the batter rolling over the ball for a weak groundout.

The home-run-percentage numbers are also interesting in the table above. Even when the pitch is way outside, pulled baseballs are more likely to result in home runs. For balls hit to the opposite field, home runs are higher when the pitch is slightly outside, even though wOBA is lower. The gains in hitting balls to the opposite field when they’re further out come from improvements in average, not power.

In our previous table, we’ve accounted for the fact that there are varying degrees of how far out a pitch can be. In the same manner that there’s a difference between a pitch that is way in/out and just barely in/out, there are also varying extremities of how severely a ball is pulled or hit to the opposite field. To help account for this, we are going to calculate horizontal spray angles for each batted ball using the formula from this extremely helpful Hardball Times article. As stated in the article, the calculations may not be perfect, and they may not align exactly with the pulled and opposite field values used earlier, but they should be very similar and will allow us to analyze batted balls at a much more granular level than we have thus far.

Once spray angles were calculated for each pitch, batted balls were split into nine separate groups. Pitch locations were divided into inside, middle, and outside, with middle pitches consisting of the central third of home plate. All pitches further out than that were considered outside, with all pitches further in considered inside. Pitches were also divided into three groups along batted-ball location, with balls hit to the middle 30° of the field placed into the middle group, and balls that were hit further in or away grouped accordingly. The table below shows the average launch speed for each of the nine groups.

As the table shows, inside pitches should be pulled, with the optimal angle drifting closer to the opposite field as the pitch gets further away. However, even for outside pitches, balls are still hit harder to the middle third of the field than to the away third. We can also look at wOBA for these groups, which will show relatively similar results.

One interesting result here is that batters are actually slightly more successful when pulling the ball than hitting it up the middle if it’s in the heart of the plate. We still see the same shift, however, where the further away a pitch is, the further away it should be hit. Maybe the old conventional wisdom is on to something after all. We can help visualize this with the following heat map, which shows how batted-ball launch speed varies based on the horizontal location of the pitch and the spray angle.

In the plot above, negative spray angles are balls that are pulled, with positive spray angles being hit to the opposite field. Zero is the middle of the field. The horizontal pitch location follows a similar layout, with zero being the middle of the plate and negative values representing pitches that are inside. While it is subtle, we see that, as the distance of the pitch away from the batter increases, the spray angle of the hardest-hit balls increases as well. However, for opposite-field hits, this seems to taper off around the 20° mark, which we don’t really see for pulled balls

One other interesting note is that the average launch angles vary quite a bit between the different groups, as shown in the following table.

Average launch angles are much lower for pulled balls, and launch angles decrease among all batted-ball locations as the pitch moves further away.

So, is the conventional wisdom to hit the ball where it’s pitched correct? Yes, the optimal location to hit a baseball varies with the location of the pitch. As the pitch gets further outside, the optimal angle moves further towards the opposite field. However, it’s important to note that the optimal spray angle isn’t centered relative to the middle of the plate and the center of the field, and is actually offset towards the pull side. It’s also worth noting that batters still have less power when hitting to the opposite field, so it’s likely worthwhile to be selective and wait for a pitch that can be driven up the middle or pulled when possible.

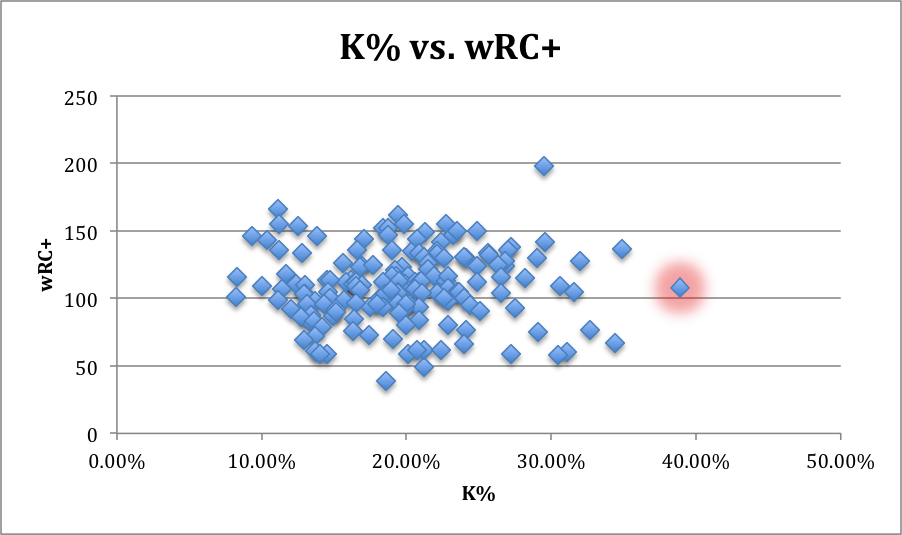

There are still a lot of other ways to cut this data outside of what I’ve described here, and I really think we’re just scratching the surface regarding the optimal offensive approach. While balls that are pulled are hit harder, batters who are more selective and wait for a pitch to pull are also more likely to get deeper in counts and strike out more often, so there’s definitely a trade-off that has to be considered. Another important note is that the tables I’ve shown above are looking at all batted balls. It could be valuable to pull similar results when only looking at pitches in or near the strike zone. It would also be interesting to see how the optimal spray angle varies based on other factors, such as the pitch type and the vertical location of the pitch.

The current analysis groups all major-league hitters together. I’d love to see a future analysis that breaks out results by the type of batter and perhaps even shows different optimal spray angles for different batter profiles. While the analysis here does help to demonstrate that there is validity to the conventional wisdom of hitting the ball where it’s pitched, there are still factors not being accounted for. One of these is the fact that we may be dealing with some sample bias, as the most powerful hitters are also likely to be the ones who attempt to pull every pitch. Accounting for different types of hitters would be a great next step in furthering this research by adjusting for the fact that hitting doesn’t have a one-size-fits-all approach.