If you haven’t read Part 1 and Part 2, you may want to go back and check them out. If you would prefer not to, this is a reminder of where these numbers came from:

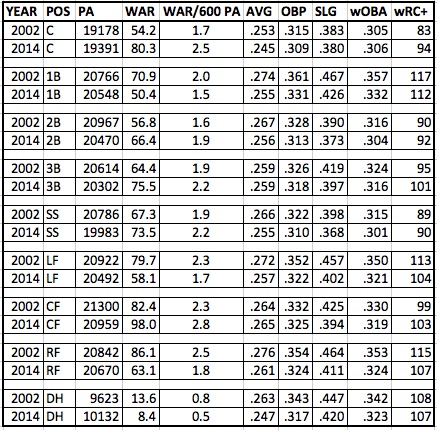

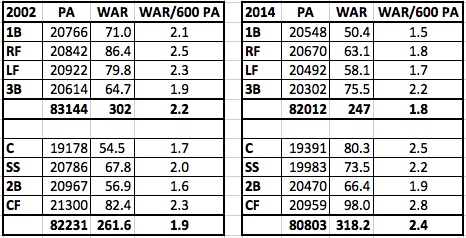

Using FanGraphs’ terrific leaderboard tools, I found statistics for all players who played at each position in 2014. The following numbers apply only to the time spent at that position. Buster Posey, for example, accumulated 462 plate appearances at catcher, 128 at first base, and 9 at DH, so his plate appearances in those amounts are included for those positions in the table below.

For position players, I calculated WAR per 600 plate appearances. For starting pitchers, I used WAR per 150 innings pitched. For relievers, I used WAR per 50 innings pitched.

In this installment of 2014 WAR Breakdown, players at each hitting position are split into six different age groups. All “small sample size” warnings apply.

CATCHER

| CATCHER |

N |

PA% |

PA |

WAR% |

WAR%dff |

WAR |

WAR/600 PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

| <23 |

8 |

5.4% |

1040 |

3.2% |

-2.1% |

2.6 |

1.5 |

.227 |

.275 |

.354 |

| 24 to 26 |

27 |

24.9% |

4829 |

23.1% |

-1.8% |

18.6 |

2.3 |

.246 |

.301 |

.391 |

| 27 to 29 |

24 |

27.5% |

5331 |

34.7% |

7.2% |

27.9 |

3.1 |

.252 |

.321 |

.403 |

| 30 to 32 |

26 |

29.2% |

5666 |

36.8% |

7.6% |

29.6 |

3.1 |

.253 |

.319 |

.385 |

| 33 to 35 |

13 |

8.5% |

1655 |

3.7% |

-4.8% |

3.0 |

1.1 |

.220 |

.310 |

.307 |

| 36 and up |

4 |

4.5% |

870 |

-1.6% |

-6.1% |

-1.3 |

-0.9 |

.218 |

.263 |

.300 |

| C |

102 |

|

19391 |

|

|

80.4 |

2.5 |

.245 |

.309 |

.380 |

The most productive age groups for catchers were the “27 to 29” and “30 to 32” age groups, with both groups averaging 3.1 WAR/600 PA. Not surprisingly, the production by catchers really starts to dwindle as they move into their mid-30’s. The “30 to 32” age group hit a combined .253/.319/.385, while the “33 to 35” age group hit just .220/.310/.307. Russell Martin will be 32 next year and just signed a 5-year, $82 million contract with the Blue Jays. Here’s hoping he ages better than most catchers, for the Blue Jays’ sake.

Best Catcher 23 and under: Mike Zunino, 23 (1.7 WAR)

Best Catcher 24 to 26: Devin Mesoraco, 26 (4.1 WAR)

Best Catcher 27 to 29: Jonathan Lucroy, 28 (6.3 WAR)

Best Catcher 30 to 32: Russell Martin, 31 (5.4 WAR)

Best Catcher 33 to 35: Carlos Ruiz, 35 (3.2 WAR)

Best Catcher 36 and up: David Ross, 37 (0.2 WAR)

FIRST BASE

| FIRST BASE |

N |

PA% |

PA |

WAR% |

WAR%dff |

WAR |

WAR/600 PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

| <23 |

5 |

2.2% |

446 |

-3.4% |

-5.5% |

-1.7 |

-2.3 |

.177 |

.276 |

.347 |

| 24 to 26 |

41 |

22.2% |

4552 |

34.0% |

11.8% |

17.2 |

2.3 |

.270 |

.340 |

.449 |

| 27 to 29 |

57 |

25.0% |

5143 |

27.3% |

2.2% |

13.8 |

1.6 |

.247 |

.328 |

.429 |

| 30 to 32 |

40 |

28.7% |

5906 |

36.6% |

7.8% |

18.5 |

1.9 |

.263 |

.336 |

.424 |

| 33 to 35 |

20 |

19.6% |

4028 |

9.3% |

-10.3% |

4.7 |

0.7 |

.253 |

.329 |

.421 |

| 36 and up |

8 |

2.3% |

473 |

-3.8% |

-6.1% |

-1.9 |

-2.4 |

.199 |

.281 |

.299 |

| 1B |

171 |

|

20548 |

|

|

50.6 |

1.5 |

.255 |

.331 |

.426 |

In 2014, first baseman aged 24 to 26 were the most productive group at the position, averaging 2.3 WAR/600 PA. The “30 to 32” group was next, at 1.9 WAR/600 PA, with the group in the middle (“27 to 29”) finishing third in this metric. The small sample sizes of young (23 and under) and old (36 and older) were quite unproductive, both averaging negative WAR per 600 PA and hitting under .200.

Best First Baseman 23 and under: Will Myers, 23 (0.0 WAR in just 3 PA)

Best First Baseman 24 to 26: Anthony Rizzo, 24 (5.6 WAR)

Best First Baseman 27 to 29: Jose Abreu, 27 (4.4 WAR)

Best First Baseman 30 to 32: Miguel Cabrera, 31 (4.9 WAR)

Best First Baseman 33 to 35: Justin Morneau, 33 (2.5 WAR)

Best First Baseman 36 and up: Raul Ibanez, 42 (0.3 WAR in 20 PA)

SECOND BASE

| SECOND BASE |

N |

PA% |

PA |

WAR% |

WAR%dff |

WAR |

WAR/600 PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

| <23 |

21 |

12.0% |

2450 |

9.8% |

-2.2% |

6.5 |

1.6 |

.246 |

.289 |

.371 |

| 24 to 26 |

43 |

24.4% |

5000 |

21.1% |

-3.4% |

14.0 |

1.7 |

.270 |

.321 |

.377 |

| 27 to 29 |

44 |

25.3% |

5173 |

26.8% |

1.5% |

17.8 |

2.1 |

.244 |

.312 |

.375 |

| 30 to 32 |

26 |

23.5% |

4802 |

30.1% |

6.6% |

20.0 |

2.5 |

.270 |

.321 |

.386 |

| 33 to 35 |

14 |

11.1% |

2281 |

12.5% |

1.3% |

8.3 |

2.2 |

.251 |

.314 |

.356 |

| 36 and up |

8 |

3.7% |

764 |

-0.2% |

-3.9% |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

.219 |

.285 |

.307 |

| 2B |

156 |

|

20470 |

|

|

66.5 |

1.9 |

.256 |

.313 |

.373 |

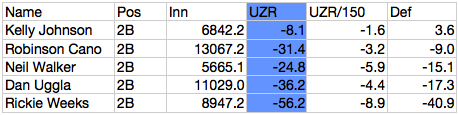

The most productive group of second basemen skewed older than you might expect. The group aged 30 to 32 had the highest WAR/600 PA and best hitting line. Overall, the three age groups ranging from age 27 to age 35 were the most productive.

Best Second Baseman 23 and under: Kolten Wong, 23 (1.8 WAR)

Best Second Baseman 24 to 26: Jose Altuve, 24 (5.0 WAR)

Best Second Baseman 27 to 29: Brian Dozier, 27 (4.6 WAR)

Best Second Baseman 30 to 32: Ian Kinsler, 32 (5.5 WAR)

Best Second Baseman 33 to 35: Chase Utley, 35 (4.2 WAR)

Best Second Baseman 36 and up: Brian Roberts, 36 (0.3 WAR)

THIRD BASE

| THIRD BASE |

N |

PA% |

PA |

WAR% |

WAR%dff |

WAR |

WAR/600 PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

| <23 |

15 |

10.2% |

2067 |

4.4% |

-5.8% |

3.3 |

1.0 |

.250 |

.292 |

.401 |

| 24 to 26 |

41 |

28.6% |

5806 |

20.6% |

-8.0% |

15.6 |

1.6 |

.250 |

.304 |

.392 |

| 27 to 29 |

48 |

34.7% |

7052 |

38.5% |

3.8% |

29.2 |

2.5 |

.256 |

.323 |

.405 |

| 30 to 32 |

26 |

16.8% |

3405 |

20.7% |

3.9% |

15.7 |

2.8 |

.266 |

.330 |

.375 |

| 33 to 35 |

12 |

6.5% |

1320 |

12.8% |

6.3% |

9.7 |

4.4 |

.307 |

.358 |

.431 |

| 36 and up |

6 |

3.2% |

652 |

3.0% |

-0.2% |

2.3 |

2.1 |

.265 |

.315 |

.396 |

| 3B |

148 |

|

20302 |

|

|

75.8 |

2.2 |

.259 |

.318 |

.397 |

Production at third base in 2014 skewed older. Third basemen 23 and under and 24 to 26 were the two least productive groups. The “33 to 35” group had the highest WAR/600 PA, but this was due mainly to just two players—Adrian Beltre and Juan Uribe.

Best Third Baseman 23 and under: Nolan Arenado, 23 (3.1 WAR)

Best Third Baseman 24 to 26: Kyle Seager, 26 (5.6 WAR)

Best Third Baseman 27 to 29: Josh Donaldson, 28 (6.5 WAR)

Best Third Baseman 30 to 32: Chase Headley, 30 (4.4 WAR)

Best Third Baseman 33 to 35: Adrian Beltre, 35 (5.7 WAR)

Best Third Baseman 36 and up: Aramis Ramirez, 36 (2.2 WAR)

SHORTSTOP

| LEFT FIELDER |

N |

PA% |

PA |

WAR% |

WAR%dff |

WAR |

WAR/600 PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

| <23 |

20 |

11.0% |

2197 |

11.5% |

0.5% |

8.4 |

2.3 |

.248 |

.302 |

.362 |

| 24 to 26 |

32 |

28.5% |

5696 |

19.6% |

-8.9% |

14.4 |

1.5 |

.254 |

.305 |

.353 |

| 27 to 29 |

39 |

26.3% |

5261 |

28.6% |

2.3% |

21.0 |

2.4 |

.252 |

.308 |

.374 |

| 30 to 32 |

19 |

25.9% |

5169 |

32.5% |

6.6% |

23.8 |

2.8 |

.264 |

.319 |

.384 |

| 33 to 35 |

8 |

4.6% |

923 |

7.1% |

2.5% |

5.2 |

3.4 |

.244 |

.325 |

.371 |

| 36 and up |

6 |

3.7% |

737 |

0.7% |

-3.0% |

0.5 |

0.4 |

.261 |

.314 |

.331 |

| SS |

124 |

|

19983 |

|

|

73.3 |

2.2 |

.255 |

.310 |

.368 |

At the shortstop position, the age 24 to 26 group had the largest percentage of playing time of any group, but a lower WAR/600 PA than any group except the “36 and up” group. In the “27 to 29” age group, Troy Tulowitzki had 5.2 of the group’s 21.0 WAR (24.8%) despite getting just 372 of the group’s 5261 plate appearances (7%).

Best Shortstop 23 and under: Jose Ramirez, 21 (2.1 WAR)

Best Shortstop 24 to 26: Starlin Castro, 24 (2.8 WAR)

Best Shortstop 27 to 29: Troy Tulowitzki, 29 (5.2 WAR)

Best Shortstop 30 to 32: Jhonny Peralta, 32 (5.3 WAR)

Best Shortstop 33 to 35: Jimmy Rollins, 35 (3.5 WAR)

Best Shortstop 36 and up: LittleNicky Punto, 36 (0.4 WAR)

LEFT FIELD

| LEFT FIELD |

N |

PA% |

PA |

WAR% |

WAR%dff |

WAR |

WAR/600 PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

| <23 |

16 |

6.2% |

1267 |

10.9% |

4.7% |

6.4 |

3.0 |

.265 |

.332 |

.387 |

| 24 to 26 |

52 |

27.3% |

5588 |

27.3% |

0.0% |

16.0 |

1.7 |

.263 |

.320 |

.428 |

| 27 to 29 |

65 |

26.8% |

5500 |

26.8% |

0.0% |

15.7 |

1.7 |

.256 |

.314 |

.396 |

| 30 to 32 |

44 |

23.7% |

4852 |

28.7% |

5.0% |

16.8 |

2.1 |

.255 |

.332 |

.393 |

| 33 to 35 |

24 |

14.6% |

2997 |

8.5% |

-6.1% |

5.0 |

1.0 |

.254 |

.328 |

.396 |

| 36 and up |

7 |

1.4% |

288 |

-2.2% |

-3.6% |

-1.3 |

-2.7 |

.211 |

.248 |

.292 |

| LF |

208 |

|

20492 |

|

|

58.6 |

1.7 |

.257 |

.322 |

.402 |

Thanks to Christian Yelich, the most-productive group of left fielders in WAR/600 PA was the group of player’s aged 23 and under. It’s interesting to see the WAR/600 PA drop-off from the “30 to 32” group to the “33 to 35” group. The “33 to 35” group hit nearly as well as the younger group, but they had a couple of particularly bad fielders (Rajai Davis and Matt Holliday) who brought their WAR total down.

Best Left Fielder 23 and under: Christian Yelich, 22 (4.2 WAR)

Best Left Fielder 24 to 26: Justin Upton, 26 (4.1 WAR)

Best Left Fielder 27 to 29: Michael Brantley, 27 (4.5 WAR)

Best Left Fielder 30 to 32: Alex Gordon, 30 (6.6 WAR)

Best Left Fielder 33 to 35: Matt Holliday, 34 (3.8 WAR)

Best Left Fielder 36 and up: Endy Chavez, 36 (0.1 WAR)

CENTER FIELD

| CENTER FIELD |

N |

PA% |

PA |

WAR% |

WAR%dff |

WAR |

WAR/600 PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

| <23 |

21 |

16.8% |

3523 |

22.8% |

6.0% |

22.3 |

3.8 |

.265 |

.325 |

.426 |

| 24 to 26 |

36 |

21.0% |

4395 |

17.7% |

-3.2% |

17.3 |

2.4 |

.266 |

.316 |

.365 |

| 27 to 29 |

43 |

39.3% |

8231 |

41.9% |

2.6% |

40.9 |

3.0 |

.264 |

.327 |

.405 |

| 30 to 32 |

25 |

18.4% |

3859 |

16.3% |

-2.1% |

15.9 |

2.5 |

.268 |

.330 |

.383 |

| 33 to 35 |

12 |

4.4% |

919 |

1.5% |

-2.8% |

1.5 |

1.0 |

.259 |

.330 |

.378 |

| 36 and up |

3 |

0.2% |

32 |

-0.3% |

-0.5% |

-0.3 |

-5.6 |

.167 |

.192 |

.167 |

| CF |

140 |

|

20959 |

|

|

97.6 |

2.8 |

.265 |

.325 |

.394 |

Mike Trout had 664 of the 3523 plate appearances (19%) credited to players 23 and under, but 34% of the WAR for this group. With Trout, Billy Hamilton (3.5 WAR) and Marcell Ozuna (3.4 WAR) all in the 23 and under group, this was the most productive collection of players of any of the age groups in WAR/600 PA. Center field is a young person’s position. Just 4.6% of the plate appearances by center fielders went to players 33 and over.

Best Center Fielder 23 and under: Mike Trout, 22 (7.5 WAR)

Best Center Fielder 24 to 26: Juan Lagares, 25 (3.8 WAR)

Best Center Fielder 27 to 29: Andrew McCutchen, 27 (6.8 WAR)

Best Center Left Fielder 30 to 32: Jacoby Ellsbury, 30 (3.9 WAR)

Best Center Fielder 33 to 35: Rajai Davis, 33 (1.0 WAR)

Best Center Fielder 36 and up: Reed Johnson, 37 (0.0 WAR)

RIGHT FIELD

| RIGHT FIELD |

N |

PA% |

PA |

WAR% |

WAR%dff |

WAR |

WAR/600 PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

| <23 |

23 |

11.6% |

2403 |

7.4% |

-4.2% |

4.7 |

1.2 |

.248 |

.317 |

.391 |

| 24 to 26 |

50 |

21.8% |

4509 |

34.2% |

12.4% |

21.6 |

2.9 |

.260 |

.327 |

.428 |

| 27 to 29 |

50 |

18.4% |

3802 |

19.3% |

0.9% |

12.2 |

1.9 |

.261 |

.315 |

.410 |

| 30 to 32 |

45 |

23.2% |

4794 |

14.6% |

-8.6% |

9.2 |

1.2 |

.254 |

.315 |

.388 |

| 33 to 35 |

22 |

15.3% |

3159 |

22.0% |

6.7% |

13.9 |

2.6 |

.274 |

.353 |

.435 |

| 36 and up |

10 |

9.7% |

2003 |

2.4% |

-7.3% |

1.5 |

0.4 |

.271 |

.316 |

.418 |

| RF |

200 |

|

20670 |

|

|

63.1 |

1.8 |

.261 |

.324 |

.411 |

Players 23 and under had 4.7 WAR as a group in 2014. Yasiel Puig had 3.7 of that total. In the “30 to 32” age group, Hunter Pence (4.7 WAR) had more than half of the total WAR (9.2) for the group.

Best Right Fielder 23 and under: Yasiel Puig, 23 (3.7 WAR)

Best Right Fielder 24 to 26: Giancarlo Stanton, 24 (6.2 WAR)

Best Right Fielder 27 to 29: Mat Kemp, 29 (2.4 WAR)

Best Right Fielder 30 to 32: Hunter Pence, 31 (4.7 WAR)

Best Right Fielder 33 to 35: Jose Bautista, 33 (6.1 WAR)

Best Right Fielder 36 and up: Marlon Byrd, 36 (1.9 WAR)

DESIGNATED HITTER

| DH |

N |

PA% |

PA |

WAR% |

WAR%dff |

WAR |

WAR/600 PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

| <23 |

20 |

3.2% |

326 |

15.6% |

12.3% |

1.4 |

2.6 |

.287 |

.347 |

.461 |

| 24 to 26 |

62 |

9.1% |

927 |

-15.6% |

-24.7% |

-1.4 |

-0.9 |

.224 |

.284 |

.397 |

| 27 to 29 |

72 |

24.8% |

2510 |

11.1% |

-13.7% |

1.0 |

0.2 |

.248 |

.307 |

.412 |

| 30 to 32 |

58 |

22.7% |

2304 |

-7.8% |

-30.5% |

-0.7 |

-0.2 |

.237 |

.311 |

.381 |

| 33 to 35 |

32 |

25.1% |

2547 |

91.1% |

66.0% |

8.2 |

1.9 |

.256 |

.341 |

.466 |

| 36 and up |

17 |

15.0% |

1518 |

5.6% |

-9.4% |

0.5 |

0.2 |

.238 |

.312 |

.424 |

| DH |

261 |

|

10132 |

|

|

9.0 |

0.5 |

.247 |

.317 |

.420 |

There wasn’t much WAR accumulated by players at the DH position in 2014. It’s hard to produce WAR with no defensive value and a strong positional adjustment.

Best DH 23 and under: Kennys Vargas, 23 (0.7 WAR)

Best DH 24 to 26: Yan Gomes, 26 (1.0 WAR)

Best DH 27 to 29: Chris Carter, 27 (2.2 WAR)

Best DH 30 to 32: Adam Lind, 30 (0.9 WAR)

Best DH 33 to 35: Victor Martinez, 35 (3.9 WAR)

Best DH 36 and up: David Ortiz, 38 (2.7 WAR)

PITCHER (HITTING)

| PITCHERS |

N |

PA% |

PA |

WAR |

WAR/600 PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

| <23 |

32 |

9.6% |

527 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

.138 |

.167 |

.182 |

| 24 to 26 |

109 |

27.6% |

1516 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

.123 |

.154 |

.159 |

| 27 to 29 |

78 |

27.6% |

1515 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

.121 |

.157 |

.151 |

| 30 to 32 |

48 |

17.3% |

950 |

-1.6 |

-1.0 |

.119 |

.147 |

.147 |

| 33 to 35 |

26 |

10.6% |

580 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

.130 |

.154 |

.148 |

| 36 and up |

15 |

7.3% |

403 |

-1.2 |

-1.8 |

.097 |

.121 |

.114 |

| PITCHERS |

308 |

|

5491 |

-2.6 |

-0.3 |

.122 |

.153 |

.152 |

Ha! Pitchers hitting. That’s funny.

Best Pitcher (hitting) 23 and under: Shelby Miller, 23 (0.5 WAR)

Best Pitcher (hitting) 24 to 26: Madison Bumgarner, 24 (1.2 WAR)

Best Pitcher (hitting) 27 to 29: Travis Wood, 27 (1.0 WAR)

Best Pitcher (hitting) 30 to 32: Zack Greinke, 30 (0.7 WAR)

Best Pitcher (hitting) 33 to 35: Dan Haren, 33 (0.3 WAR)

Best Pitcher (hitting) 36 and up: Bronson Arroyo, 37 (0.1 WAR)

PINCH-HITTER

| PH |

N |

PA% |

PA |

WAR |

WAR/600 PA |

AVG |

OBP |

SLG |

| <23 |

57 |

4.9% |

271 |

0.9 |

2.0 |

.268 |

.318 |

.362 |

| 24 to 26 |

157 |

24.8% |

1361 |

-0.3 |

-0.1 |

.216 |

.280 |

.325 |

| 27 to 29 |

165 |

29.1% |

1598 |

1.4 |

0.5 |

.214 |

.292 |

.333 |

| 30 to 32 |

114 |

22.1% |

1211 |

1.8 |

0.9 |

.212 |

.302 |

.336 |

| 33 to 35 |

53 |

11.3% |

620 |

-1.8 |

-1.7 |

.174 |

.264 |

.270 |

| 36 and up |

28 |

7.7% |

422 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

.226 |

.310 |

.284 |

| PH |

574 |

|

5483 |

2.2 |

0.2 |

.213 |

.291 |

.322 |

Pinch-hitters hitting are only slightly less funny than pitchers hitting. Players 23 and under were better pinch-hitters than any other age group.

Best Pinch-Hitter 23 and under: Cory Spangenberg, 23 (0.3 WAR)

Best Pinch-Hitter 24 to 26: Lonnie Chisenhall, 25 (0.4 WAR)

Best Pinch-Hitter 27 to 29: Delmon Young, 28 (0.6 WAR)

Best Pinch-Hitter 30 to 32: John Mayberry, Jr., 30 (0.8 WAR)

Best Pinch-Hitter 33 to 35: Jeff Baker, 33 (0.3 WAR)

Best Pinch-Hitter 36 and up: Lyle Overbay, 37 (0.4 WAR)

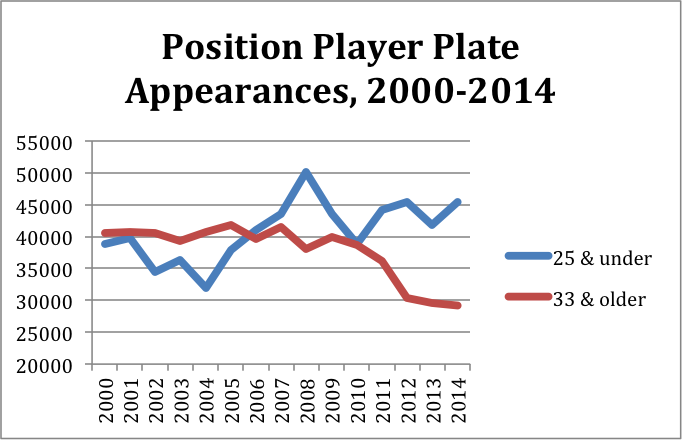

Next up is a comparison of WAR in 2014 to WAR in 2002.