Being Sunny About the Brewers

The link the Brewers have to being a very bad baseball team revolves around what we assume they will do, and really, what they should do. But, before speaking of what they will do, it’s worth examining what David Stearns has done since taking over control of the team. The off-season has been a flurry of facially insignificant moves. Here, is a list of them:

- Luis Sardinas was exchanged for Ramon Flores, an outfield prospect with the seemingly equivalent middling value of Sardinas as an infield prospect, in a trade with the Mariners

- Javier Betancourt, a younger infield prospect of middling value, was acquired from the Tigers in return for Francisco Rodriguez

- Jonathan Villar was acquired from the Astros in return for a Cy Sneed, a low-level pitching prospect

- Jason Rogers, a 27 year old first base prospect sure to see some MLB playing time this year, was traded to Pittsburgh in return for Keon Broxton, an extremely athletic prospect that profiles as a potential versatile and competent fourth outfielder, in addition to pitcher Trey Supak

- Adam Lind was sent to the Mariners in return for a trio of young, but not highly touted pitching prospects who have struck batters out at low-levels. Carlos Herrera (18), Daniel Missaki (19), and Freddy Peralta (19) are all lottery tickets, but one could always be a winner

They then went about picking up all your favorite team’s former favorite prospects, much like the Astros did when Stearns was working for them. Garin Cecchini was acquired from the Red Sox for cash; Will Middlebrooks was signed to a minor league contract; and Josmil Pinto was claimed off waivers.

Most recently, they replaced Jason Rogers and Adam Lind with Chris Carter, leaving them nearly where they started at first base, except they received five respectable prospects in return for the two first basemen sent out. Steamer projects Carter to post the best wOBA of the three (.333). There’s no loss occurring for the Brewers presently, with the potential of a marginal to hefty gain in the future.

The shuffling of first basemen has Milwaukee walking away with four young starters and a defensively capable outfielder. If one of those starters turns into a back-of-the-rotation pitcher and Broxton turns into a reliable major-league bench player then Milwaukee has won. Really, they win if any of these guys provide only one year of some sort of average major-league contribution, and they only lose if Rogers has an against all odds late-aged prospect emergence.

All of this happened before the re-build. The Brewers managed to maintain their same level of mediocrity, except they gained seven prospects to fill a depleted, and for the most part barren, farm system.

That’s the most exciting part of this. Stearns turned two prospects (Sardinas and Sneed) and three players that offered no value above what is currently on the roster (Francisco Rodriguez, Adam Lind, and Jason Rogers) into seven young prospects and a respectable utility infielder (Villar). The Brewers maintained all of their assets during the process. Now Stearns can focus on moving the real value for the type of players needed to drive a successful re-build.

First, take stock of what the Brewers have.

Jonathan Lucroy is still a very good catcher; Ryan Braun is still a very good outfielder; Khris Davis is an above average outfielder; Jean Segura and Scooter Gennett are an average middle infield; Chris Carter is a powerful first baseman; Wily Peralta and Jimmy Nelson resemble the kind of pitchers that are getting $70-$80 million in guaranteed contracts this winter, and the bullpen has capable arms in Will Smith, Michael Blazek, Jermey Jeffress and Corey Knebel.

Lucroy and Smith stand out among this group. They are very good players on very good contracts.

Jeff Sullivan wrote an article attempting to determine Lucroy’s value in a trade with the Rangers. In the end, he settled on a prospect package of Dillon Tate and Lewis Brinson. This seems right. These are two prospects you find in the second-half of Top 100 lists.

This would be a similar return to what the Brewers received from the Astros last year in the Carlos Gomez trade. They acquired Domingo Santana and Brett Phillips, two good-to-very-good outfield prospects. Gomez and Lucroy bear some similarities, in the sense that they field positions with limited talent and are above-average hitters and very good fielders at their positions. They both share an injury history that is not scary, but does give you pause, and they are both on below-market contracts for two more seasons (Gomez had two years on his contract entering 2015).

Just like teams do not have a wide selection of center fielders in the middle of the season, they have less of a selection of catchers that could add one to two wins after the trade deadline. If Lucroy stays healthy and plays like he did in 2012 and 2013, even less than his prime 2014, he is a rare commodity for a team that could upgrade at catcher.

You wouldn’t have much reason to know about the Milwaukee Brewers’ setup man, but you should know more Will Smith. He’s likely to close for the team this year after posting a declining 3.25 and 2.47 FIP over the past two seasons. He’s doesn’t light up a radar gun (with an average fastball velocity of 93.3 mph), but his slider has ranked the 10th-most effective among qualified relievers over that period (12.2 runs above average). His fastball leaves a little to be desired and it may keep him from being a dominant closer, however, he is a near elite left-handed reliever that is capable of pitching successfully against right-handed hitters as well (he actually did much better again right-handers in 2015, allowing a .545 OPS against right-handed hitters and a .785 against left-handed hitters, but did the opposite in 2014). Those kind of relievers fetch a lot in return at the trade deadline, particularly with an additional three years of team control beyond 2016.

In 2015 the Athletics received Corey Meisner from the Mets for Tyler Clippard, an aging, soon to be free agent Tyler Clippard. Two years ago the Orioles surrendered Eduardo Rodriguez to the Red Sox for soon to be free agent Andrew Miller. Smith isn’t Miller, but with continued success in 2016 he’ll be much more than Tyler Clippard was last July. Any acquisition in between the type of players Meisner and Rodriguez were at the time they were traded would be a haul for the Brewers.

This is the kind of situation that gets turned around quickly if the right decisions are made because of the small decisions made by Stearns and the new Brewers regime this off-season. Trades that will send Lucroy and Smith away from the team should return prospects that will slot into the top half of the farm system which already includes Domingo Santana, Brett Phillips, and Orlando Arcia. Stearns stacked the lower end of the system with a bunch of lottery tickets this off-season and if any hit the Brewers will accelerate the pace of their re-build even further.

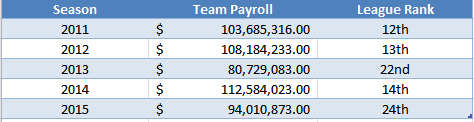

Milwaukee is not a wealthy team, but they have proven in the past that they are not allergic to spending on free agents. If they catch the right breaks then they could be a couple of big free agent signings from being a competitive team in a competitive division a couple seasons from now.

You can see the path this team is taking by examining what they have done since October ended. Fans should enjoy the excitement of potential and embrace the pain of losing for now because it shouldn’t last that long. The wins will be all the sweeter when they start to come.

The following projections for 2016 were made using Steamer Projections. The projections are based on their roster as of 1/22/16, not on how it will change throughout the season.

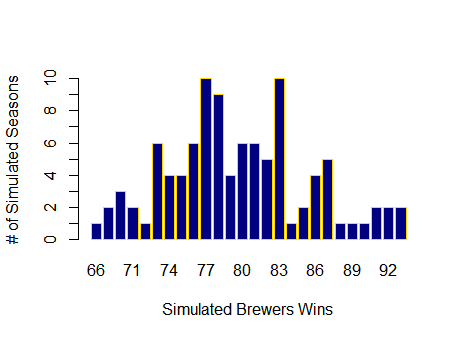

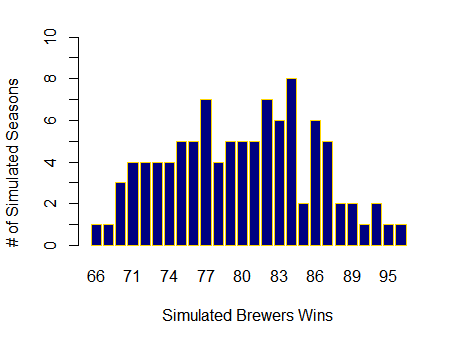

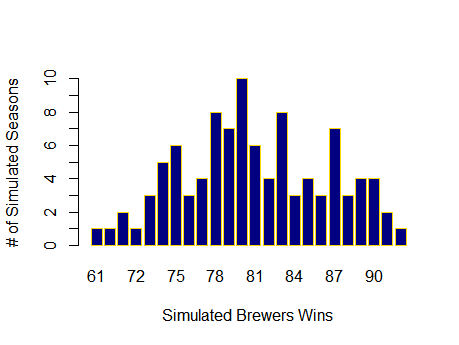

The graphs shown below are three separate simulations of the Brewers playing a 162 game season 100 times. It represents the range of outcomes a team with their projected winning percentage could experience.

2016 Brewers wOBA Expected Runs — 680 (.313 wOBA)

2016 Brewers FIP and Def Expected Runs — 687 (4.2 FIP, -18.8 Def)

2016 Brewers Pythagorean W-L — 80–82