Well, here we are: Over 100 games into the season and Bryce Harper has yet to break out of his slump. When Bryce came to the Majors back in 2012 he was one of the most hyped prospects since Alex Rodriguez broke into the bigs as a 19-year-old shortstop. The pressure, I’m sure, was immense, and through his first three seasons Harper had put up good numbers, but had yet to establish himself as the superstar we all thought he’d be. Something clicked in 2015 though, as he posted an amazing 9.5 WAR, 197 wRC+, and 0.461 wOBA, all best in the MLB by a fair margin. We all thought he’d done it, he had exceeded expectations and was ready to join Mike Trout as one of the most exciting, talented, and productive players in the game. His 1.5 WAR, 180 wRC+, and 0.443 wOBA through April of 2016 merely affirmed this sentiment.

Here we are. 2.8 WAR, 115 wRC+, and 0.346 wOBA. To be fair, these are by no means terrible numbers. He is still creating runs at a decently better rate than the average MLB player, with much of the credit going towards his MLB-leading 18.2 BB% and his 0.214 ISO. His defense has also been very good this year, helping to raise his WAR to 41st in the MLB. No, I am not saying Harper is a bad player, I’m just saying he is worse than the Bryce Harper we saw in 2015. We were all ready to call him a superstar (heck, we even voted him into a starting spot at this year’s All-Star Game), but now he’s taken this step back and we have no choice now but to start questioning his superstar status. Let’s take a look both at what might be causing this slump, and what Bryce could do to bust out of it (if anything at all).

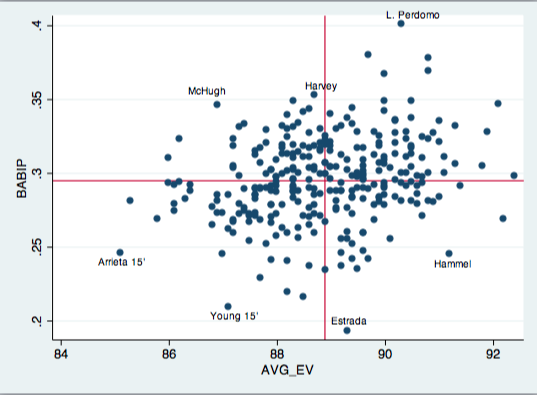

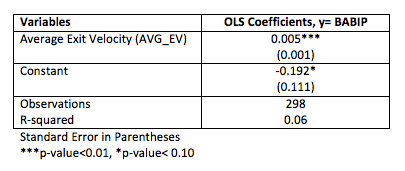

The stat that jumps out at me most is his BABIP. The MLB average is exactly 0.300 this year, and Bryce has a career mark of 0.317. Bryce isn’t too far into his career, and while it’s possible that his 0.369 BABIP last season was an anomaly, it’s certainly safe to say that Bryce is definitively above average in this area. This season his BABIP has dipped down to 0.234, good enough for second to last in the MLB, ahead of only Todd Frazier (0.203). BABIP has a great degree of luck involved, in that some hitters with higher BABIPs might just get lucky (e.g. hit a little bloop into shallow right field that drops for a hit), or might be playing poor defenses (e.g. Jason Heyward would have caught that little bloop, but Jose Bautista was in right field and missed it by a foot). I believe, though, that going from 0.369 in 2015 to 0.234 in 2016 is enough of a differential to at least form the hypothesis that Bryce is struggling beyond just facing better defenses and getting less breaks.

One of the keys to figuring out this drop in production is figuring out what has changed from last year. Obviously his BABIP has declined, but why? For the most part, pitchers are throwing him the same types of pitches at the same rates, and are throwing pitches in/out of the zone at the same rates as well. He has almost the exact same swing% on pitches outside the zone, but there’s about a 5% decrease in his swing% on pitches in the zone; nothing monumental, but something we ought take note of. The greatest changes that may be observed are in his batted ball numbers, shown here:

| Year |

LD% |

GB% |

FB% |

IFFB% |

HR/FB |

GB/FB |

Pull% |

Center% |

Opposite% |

Soft% |

Medium% |

Hard% |

| 2015 |

22.2 |

38.5 |

39.3 |

5.8 |

27.3 |

0.98 |

45.4 |

33.8 |

20.8 |

11.9 |

47.2 |

40.9 |

| 2016 |

14.3 |

41.4 |

44.4 |

11.0 |

16.9 |

0.93 |

40.9 |

33.5 |

25.7 |

22.7 |

45.4 |

32.0 |

We can almost construct a narrative from these numbers: He’s hitting balls soft significantly more often, and he’s also hitting less line drives. Soft ground balls and fly balls are easier to convert into outs, and his infield fly ball% increase implies that he is hitting fly balls with less power. This explains why his home run rate is down. Where he was previously hitting hard line drives and grounders, and turning fly balls into home runs, he is now hitting softer, more easily-fielded grounders and popups, resulting in a steep decline in BABIP.

But this isn’t a cause, it’s a symptom. Again, we are forced to ask why it is that Bryce isn’t hitting balls as hard, and why he’s hitting less line drives? Bryce has been known for having great plate discipline, something that generally hasn’t changed over the last two years. At the surface, we see that he still has a very high walk rate, lays off pitches outside of the zone, and is one of the more patient hitters in baseball. However, one stat that caught my eye was his contact% on pitches outside the zone (and even inside the zone). His O-contact% went from 60.9% to 67.4%, and even his Z-contact% increased from 84.4% to 87.7%. This can be visualized here:

For the 2015 season

Bryce Harper Contact% vs All Pitchers

Season: 2015-04-06 to 2015-10-04 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 2619 | View: Catcher |

|

100 %

|

|

|

|

44 %

|

|

|

|

|

50 %

|

|

39 %

|

51 %

|

61 %

|

75 %

|

72 %

|

80 %

|

88 %

|

100 %

|

|

|

70 %

|

59 %

|

66 %

|

78 %

|

80 %

|

88 %

|

91 %

|

95 %

|

|

|

77 %

|

77 %

|

78 %

|

84 %

|

87 %

|

91 %

|

98 %

|

97 %

|

|

|

71 %

|

71 %

|

79 %

|

83 %

|

87 %

|

90 %

|

90 %

|

93 %

|

96 %

|

|

|

75 %

|

85 %

|

88 %

|

88 %

|

88 %

|

92 %

|

88 %

|

82 %

|

|

|

76 %

|

80 %

|

83 %

|

84 %

|

84 %

|

85 %

|

81 %

|

77 %

|

|

|

81 %

|

74 %

|

79 %

|

76 %

|

79 %

|

78 %

|

75 %

|

52 %

|

|

|

73 %

|

64 %

|

66 %

|

68 %

|

70 %

|

73 %

|

60 %

|

25 %

|

|

|

27 %

|

|

|

|

26 %

|

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

And for the 2016 season

Bryce Harper Contact% vs All Pitchers

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-28 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 1616 | View: Catcher |

|

100 %

|

|

|

|

60 %

|

|

|

|

|

100 %

|

|

75 %

|

23 %

|

45 %

|

76 %

|

89 %

|

97 %

|

100 %

|

100 %

|

|

|

82 %

|

75 %

|

59 %

|

70 %

|

89 %

|

97 %

|

100 %

|

100 %

|

|

|

71 %

|

77 %

|

80 %

|

86 %

|

91 %

|

98 %

|

100 %

|

100 %

|

|

|

63 %

|

73 %

|

79 %

|

78 %

|

84 %

|

92 %

|

99 %

|

100 %

|

100 %

|

67 %

|

|

74 %

|

86 %

|

84 %

|

88 %

|

86 %

|

95 %

|

99 %

|

100 %

|

|

|

69 %

|

84 %

|

82 %

|

85 %

|

89 %

|

91 %

|

85 %

|

89 %

|

|

|

84 %

|

81 %

|

74 %

|

81 %

|

81 %

|

86 %

|

68 %

|

35 %

|

|

|

88 %

|

79 %

|

74 %

|

70 %

|

78 %

|

74 %

|

69 %

|

50 %

|

|

|

40 %

|

|

|

|

39 %

|

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

There are two ways to look at this: The types of pitches Bryce is seeing, and the counts he’s getting himself into. All of this revolves around where pitchers are throwing pitches, where he’s swinging, and where he’s making contact. As you can clearly see, Bryce has been making a tangibly higher amount of contact this season. Logically, it makes sense to say that he is taking more pitches in the zone, and making weak contact where he used to just swing and miss. But that can’t be the whole story, can it? In attempting to find differences between this season and last, I merely found that regardless of what the count was, Harper was always making more contact; it didn’t matter if he was ahead, behind, or even. He was also making more contact regardless of what pitches were being thrown.

Let’s start with the types of pitches Bryce sees. We’ll split it up into fastballs (which includes 4-seamers, 2-seamers, and cutters), and secondary pitches (curveballs, sliders, and changeups). With secondary pitches, pitchers have begun to come into the zone a bit more than they used to. These charts show where pitchers are throwing Bryce non-fastballs:

2015

Bryce Harper Pitch% vs All Pitchers

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2015-04-06 to 2015-10-04 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 877 | View: Catcher |

|

0.5 %

|

|

|

|

0.2 %

|

|

|

|

|

0.2 %

|

|

0.6 %

|

0.4 %

|

0.2 %

|

0.3 %

|

0.4 %

|

0.3 %

|

0.2 %

|

0.1 %

|

|

|

0.7 %

|

0.7 %

|

0.5 %

|

0.4 %

|

0.5 %

|

0.5 %

|

0.3 %

|

0.2 %

|

|

|

0.8 %

|

0.9 %

|

1.1 %

|

0.9 %

|

0.6 %

|

0.7 %

|

0.5 %

|

0.2 %

|

|

|

1.2 %

|

1.0 %

|

1.4 %

|

1.6 %

|

1.6 %

|

1.1 %

|

0.7 %

|

0.5 %

|

0.3 %

|

0.1 %

|

|

1.5 %

|

1.6 %

|

2.0 %

|

2.0 %

|

1.4 %

|

1.0 %

|

0.7 %

|

0.3 %

|

|

|

1.7 %

|

2.1 %

|

2.0 %

|

1.9 %

|

1.7 %

|

1.2 %

|

1.0 %

|

0.7 %

|

|

|

1.8 %

|

2.1 %

|

2.3 %

|

2.3 %

|

1.8 %

|

1.3 %

|

0.8 %

|

0.7 %

|

|

|

1.6 %

|

1.9 %

|

2.0 %

|

2.0 %

|

2.1 %

|

1.4 %

|

0.8 %

|

0.5 %

|

|

|

2.9 %

|

|

|

|

3.0 %

|

|

|

|

|

2.1 %

|

2016

Bryce Harper Pitch% vs All Pitchers

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-28 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 579 | View: Catcher |

|

0.7 %

|

|

|

|

0.4 %

|

|

|

|

|

0.2 %

|

|

0.4 %

|

0.5 %

|

0.5 %

|

0.5 %

|

0.7 %

|

0.5 %

|

0.3 %

|

0.2 %

|

|

|

0.6 %

|

0.6 %

|

0.7 %

|

0.7 %

|

0.7 %

|

0.6 %

|

0.4 %

|

0.2 %

|

|

|

1.2 %

|

1.1 %

|

0.9 %

|

0.9 %

|

0.8 %

|

0.7 %

|

0.5 %

|

0.2 %

|

|

|

1.1 %

|

1.5 %

|

1.7 %

|

1.5 %

|

1.5 %

|

1.3 %

|

0.6 %

|

0.6 %

|

0.4 %

|

0.2 %

|

|

2.0 %

|

2.4 %

|

2.2 %

|

2.0 %

|

2.0 %

|

1.2 %

|

0.5 %

|

0.4 %

|

|

|

2.0 %

|

2.9 %

|

2.9 %

|

2.4 %

|

2.0 %

|

1.4 %

|

0.7 %

|

0.5 %

|

|

|

1.5 %

|

2.3 %

|

2.8 %

|

2.5 %

|

2.0 %

|

1.3 %

|

1.1 %

|

0.9 %

|

|

|

1.3 %

|

2.0 %

|

2.5 %

|

2.6 %

|

2.0 %

|

1.3 %

|

1.1 %

|

1.1 %

|

|

|

2.4 %

|

|

|

|

3.1 %

|

|

|

|

|

0.9 %

|

It is by no means a huge difference, but it’s still there. Obviously, pitchers are still mostly throwing him non-heaters down and away, they’re just getting them in the zone more frequently. How does Bryce respond to this change? Well, he’s been laying off the low pitch a bit more, and instead has attempted to hit the inside pitch. These are his swing percentages on secondary pitches:

2015

Bryce Harper Swing% vs All Pitchers

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2015-04-06 to 2015-10-04 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 877 | View: Catcher |

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

14 %

|

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

19 %

|

30 %

|

33 %

|

37 %

|

13 %

|

40 %

|

43 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

22 %

|

44 %

|

47 %

|

52 %

|

42 %

|

41 %

|

53 %

|

22 %

|

|

|

27 %

|

60 %

|

71 %

|

60 %

|

61 %

|

61 %

|

50 %

|

27 %

|

|

|

12 %

|

33 %

|

69 %

|

79 %

|

76 %

|

73 %

|

83 %

|

78 %

|

50 %

|

0 %

|

|

50 %

|

67 %

|

82 %

|

77 %

|

77 %

|

84 %

|

88 %

|

58 %

|

|

|

57 %

|

65 %

|

81 %

|

88 %

|

77 %

|

72 %

|

75 %

|

69 %

|

|

|

45 %

|

64 %

|

75 %

|

82 %

|

79 %

|

67 %

|

53 %

|

49 %

|

|

|

25 %

|

53 %

|

61 %

|

65 %

|

60 %

|

68 %

|

43 %

|

44 %

|

|

|

20 %

|

|

|

|

33 %

|

|

|

|

|

13 %

|

2016

Bryce Harper Swing% vs All Pitchers

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-28 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 579 | View: Catcher |

|

8 %

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

7 %

|

19 %

|

24 %

|

22 %

|

50 %

|

80 %

|

67 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

16 %

|

28 %

|

30 %

|

34 %

|

60 %

|

75 %

|

85 %

|

33 %

|

|

|

36 %

|

41 %

|

52 %

|

56 %

|

71 %

|

89 %

|

89 %

|

60 %

|

|

|

8 %

|

40 %

|

55 %

|

66 %

|

76 %

|

72 %

|

83 %

|

93 %

|

60 %

|

50 %

|

|

39 %

|

60 %

|

73 %

|

75 %

|

73 %

|

58 %

|

64 %

|

77 %

|

|

|

44 %

|

56 %

|

73 %

|

69 %

|

72 %

|

67 %

|

56 %

|

53 %

|

|

|

52 %

|

50 %

|

67 %

|

70 %

|

71 %

|

59 %

|

56 %

|

47 %

|

|

|

54 %

|

52 %

|

50 %

|

58 %

|

54 %

|

46 %

|

51 %

|

53 %

|

|

|

13 %

|

|

|

|

30 %

|

|

|

|

|

18 %

|

This also means that those non-fastballs are being called as strikes more frequently (assuming that umpires are generally going to call pitches in the zone as strikes). As we can see in his contact% charts, this season Bryce has been making contact at an extremely high rate on those high and inside pitches, and softer pitches have been absolutely no exception. In fact, he’s been making contact with the high and inside non-heaters more than he is with high and inside fastballs. What are the implications of this? Let’s look at his slugging% against secondary pitches:

2015

Bryce Harper SLG/P vs All Pitchers

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2015-04-06 to 2015-10-04 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 877 | View: Catcher |

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.044

|

.059

|

.065

|

.121

|

.091

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.154

|

.151

|

.244

|

.222

|

.196

|

.217

|

.077

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.254

|

.477

|

.357

|

.458

|

.173

|

.113

|

.062

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

.160

|

.469

|

.503

|

.503

|

.282

|

.111

|

.047

|

.000

|

|

|

.209

|

.218

|

.349

|

.475

|

.285

|

.109

|

.042

|

.000

|

|

|

.176

|

.207

|

.222

|

.353

|

.201

|

.061

|

.018

|

.000

|

|

|

.049

|

.098

|

.108

|

.246

|

.147

|

.024

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.009

|

|

|

|

.040

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

2016

Bryce Harper SLG/P vs All Pitchers

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-28 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 579 | View: Catcher |

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.056

|

.100

|

.200

|

.333

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.030

|

.094

|

.143

|

.083

|

.308

|

.167

|

|

|

.045

|

.122

|

.214

|

.146

|

.146

|

.056

|

.056

|

.200

|

|

|

.042

|

.085

|

.084

|

.325

|

.203

|

.069

|

.029

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

.039

|

.040

|

.065

|

.108

|

.062

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.093

|

.091

|

.105

|

.101

|

.175

|

.077

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.190

|

.152

|

.113

|

.203

|

.167

|

.094

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.086

|

.116

|

.078

|

.067

|

.092

|

.037

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.014

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

Slugging% is by no means a perfect measure of a hitter’s ability. Yet, in this case, it gives us a decent idea of which locations a hitter is making solid contact. In his 2015 campaign he was able to get his arms extended and drive curveballs with great power. This season he is attempting to pull the ball more, and it’s resulting in weaker contact. While he is able to drive the inside breaking ball at a pretty decent rate, I suspect that he’s opening up his stance, which can occasionally result in a hard-hit ball, but will often result in a weak fly ball to the opposite field, or a weak grounder to the pull side. The fact that he’s swinging so much more frequently at inside pitches would also be reason to guess that as he’s swinging at breaking balls out over the plate he is still attempting to pull them, as opposed to going with the pitch. Further evidence of this comes from looking at how he hits breaking balls from lefties (curving away from him), versus how he hits them from righties (curving towards him).

2015

Bryce Harper SLG/P vs L

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2015-04-06 to 2015-10-04 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 287 | View: Catcher |

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.067

|

.111

|

.182

|

.118

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.400

|

.238

|

.345

|

.450

|

.320

|

.067

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.667

|

.846

|

.417

|

.711

|

.345

|

.154

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

.214

|

.727

|

.444

|

.450

|

.314

|

.300

|

.095

|

.000

|

|

|

.070

|

.174

|

.279

|

.417

|

.188

|

.182

|

.120

|

.000

|

|

|

.083

|

.042

|

.130

|

.508

|

.361

|

.133

|

.077

|

.000

|

|

|

.028

|

.020

|

.000

|

.219

|

.320

|

.071

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

Bryce Harper SLG/P vs R

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2015-04-06 to 2015-10-04 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 590 | View: Catcher |

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

.033

|

.040

|

.000

|

.125

|

.222

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.095

|

.115

|

.184

|

.116

|

.077

|

.500

|

.182

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.164

|

.361

|

.333

|

.341

|

.077

|

.074

|

.182

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

.136

|

.379

|

.525

|

.520

|

.265

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.292

|

.248

|

.390

|

.500

|

.314

|

.068

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.234

|

.310

|

.272

|

.278

|

.148

|

.048

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.067

|

.145

|

.163

|

.255

|

.108

|

.015

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.027

|

|

|

|

.048

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

He even seems to do better against lefties. Against both of them, however, he clearly is able to see the pitch that will eventually break across the middle/outer half of the plate, and drive it with power. Let’s head over to 2016:

Bryce Harper SLG/P vs L

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-28 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 180 | View: Catcher |

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.500

|

.500

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.100

|

.571

|

.200

|

|

|

.000

|

.087

|

.211

|

.125

|

.000

|

.000

|

.100

|

.333

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.059

|

.312

|

.400

|

.118

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.033

|

.071

|

.121

|

.059

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.029

|

.057

|

.096

|

.027

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.029

|

.096

|

.109

|

.053

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.037

|

.077

|

.045

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

Bryce Harper SLG/P vs R

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-28 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 399 | View: Catcher |

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.167

|

.200

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.045

|

.214

|

.294

|

.071

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.083

|

.154

|

.217

|

.156

|

.222

|

.091

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.053

|

.125

|

.102

|

.333

|

.102

|

.049

|

.043

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

.052

|

.043

|

.062

|

.103

|

.065

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.150

|

.109

|

.109

|

.129

|

.222

|

.129

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.393

|

.192

|

.115

|

.257

|

.205

|

.120

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.158

|

.153

|

.078

|

.072

|

.108

|

.043

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.016

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

While his production has decreased against both righties and lefties, it is clear that the disparity is much larger when it comes to lefties. This is because Bryce is able to get away with trying to pull the ball against righties, as the ball is curving towards him. This makes pulling the ball a much more natural motion. Against lefties, the only breaking balls he is hitting are the ones that start inside and break right to the inside part of the plate, and the pitches that break to be right down the middle. It is the non-fastballs that are low and on the outer part of the plate that he is unable to drive, especially the ones being thrown by lefties. He’s opening up more, which also explains why his pull% hasn’t gone up (in fact it’s gone down). When he’s open, it’s hard to drive the outside pitch even if you make contact with it intending to hit it to the opposite field. Instead, he’s making that weak contact that results in outs.

Looking solely at secondary pitches, the narrative becomes: Bryce is taking the pitches that are out over the plate, and is instead swinging at pitches that are high and inside. He has a tendency to attempt to open up to the ball, and while he can sometimes get away with it against righties, lefties have been able to essentially shut him down. He is also making much more contact with all of these pitches, meaning that he’s putting more balls in play, yes, but they are weak balls that are easy to field, and are thus resulting in outs. With this mindset, even trying to hit the ball to the opposite field becomes more difficult, and all of this culminates in a lower BABIP.

Next, let’s look at how he’s handling fastballs. One thing that quickly becomes evident is the fact that Harper has been swinging at fastballs a lot less this year, especially ones up in the zone.

2015

Bryce Harper Swing% vs All Pitchers

Pitches: FA, FC, FT

Season: 2015-04-06 to 2015-10-04 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 1443 | View: Catcher |

|

3 %

|

|

|

|

26 %

|

|

|

|

|

11 %

|

|

38 %

|

67 %

|

77 %

|

90 %

|

88 %

|

59 %

|

33 %

|

22 %

|

|

|

45 %

|

65 %

|

79 %

|

89 %

|

91 %

|

78 %

|

56 %

|

38 %

|

|

|

34 %

|

66 %

|

79 %

|

87 %

|

88 %

|

78 %

|

56 %

|

52 %

|

|

|

7 %

|

35 %

|

63 %

|

78 %

|

80 %

|

81 %

|

75 %

|

54 %

|

46 %

|

0 %

|

|

37 %

|

52 %

|

70 %

|

70 %

|

70 %

|

61 %

|

46 %

|

43 %

|

|

|

27 %

|

43 %

|

51 %

|

59 %

|

59 %

|

52 %

|

31 %

|

25 %

|

|

|

12 %

|

28 %

|

42 %

|

45 %

|

51 %

|

47 %

|

29 %

|

11 %

|

|

|

11 %

|

13 %

|

30 %

|

31 %

|

29 %

|

30 %

|

26 %

|

9 %

|

|

|

6 %

|

|

|

|

6 %

|

|

|

|

|

7 %

|

2016

Bryce Harper Swing% vs All Pitchers

Pitches: FA, FC, FT

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-29 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 888 | View: Catcher |

|

4 %

|

|

|

|

25 %

|

|

|

|

|

9 %

|

|

6 %

|

27 %

|

50 %

|

54 %

|

66 %

|

58 %

|

50 %

|

22 %

|

|

|

32 %

|

46 %

|

67 %

|

75 %

|

77 %

|

68 %

|

58 %

|

35 %

|

|

|

42 %

|

66 %

|

80 %

|

72 %

|

74 %

|

74 %

|

59 %

|

32 %

|

|

|

7 %

|

42 %

|

61 %

|

78 %

|

76 %

|

68 %

|

73 %

|

64 %

|

35 %

|

0 %

|

|

35 %

|

53 %

|

66 %

|

76 %

|

79 %

|

72 %

|

59 %

|

38 %

|

|

|

24 %

|

45 %

|

52 %

|

63 %

|

67 %

|

57 %

|

35 %

|

21 %

|

|

|

12 %

|

34 %

|

45 %

|

48 %

|

42 %

|

30 %

|

15 %

|

3 %

|

|

|

4 %

|

23 %

|

33 %

|

42 %

|

43 %

|

26 %

|

20 %

|

6 %

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

13 %

|

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

His swing% on fastballs in other areas of the zone is roughly the same; it’s really just those high and down-the-middle fastballs that he’s suddenly laying off of more. And yet, just as with non-fastballs, Harper still has been managing to make more contact this year, especially on pitches high and inside, as well as pitches low and out of the zone. How has that translated in terms of his slugging%?

2015

Bryce Harper SLG/P vs All Pitchers

Pitches: FA, FC, FT

Season: 2015-04-06 to 2015-10-04 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 1443 | View: Catcher |

|

.017

|

|

|

|

.070

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

.013

|

.000

|

.037

|

.206

|

.155

|

.297

|

.154

|

.000

|

|

|

.094

|

.189

|

.136

|

.117

|

.234

|

.176

|

.187

|

.088

|

|

|

.046

|

.247

|

.466

|

.236

|

.257

|

.257

|

.140

|

.167

|

|

|

.011

|

.018

|

.088

|

.239

|

.319

|

.226

|

.236

|

.176

|

.162

|

.000

|

|

.034

|

.116

|

.227

|

.279

|

.303

|

.169

|

.176

|

.092

|

|

|

.027

|

.082

|

.246

|

.234

|

.265

|

.135

|

.050

|

.056

|

|

|

.055

|

.063

|

.181

|

.214

|

.217

|

.105

|

.011

|

.000

|

|

|

.022

|

.044

|

.118

|

.137

|

.095

|

.086

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.016

|

|

|

|

.028

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

2016

Bryce Harper SLG/P vs All Pitchers

Pitches: FA, FC, FT

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-29 | Count: All Counts | Total Pitches: 888 | View: Catcher |

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.060

|

.100

|

.000

|

|

|

.018

|

.169

|

.115

|

.000

|

.000

|

.038

|

.226

|

.176

|

|

|

.063

|

.145

|

.277

|

.067

|

.000

|

.012

|

.057

|

.107

|

|

|

.000

|

.090

|

.161

|

.103

|

.077

|

.068

|

.107

|

.062

|

.019

|

.000

|

|

.099

|

.143

|

.161

|

.101

|

.135

|

.336

|

.148

|

.042

|

|

|

.096

|

.107

|

.248

|

.318

|

.256

|

.318

|

.167

|

.032

|

|

|

.027

|

.040

|

.173

|

.352

|

.196

|

.101

|

.067

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.034

|

.170

|

.159

|

.018

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

What immediately jumps out at you is the large hole in the top part of the zone this year where Bryce is generating virtually no production. His production on low fastballs is closer to on par with last season, but up in the zone (the same area where he isn’t swinging nearly as often) he can’t get anything going. Why is this? With fastballs it’s a little more simple than with breaking balls in some aspects: For whatever reason he’s laying off fastballs in the zone, and he’s making weak contact with fastballs both high and inside, and down and away (which is where pitchers throw him fastballs most frequently). He’s giving pitchers more opportunities to throw fastballs out of the zone too. The big question mark comes at why he can’t do anything with those high fastballs specifically?

The answer isn’t too straightforward, but I do think that a large part of it is what types of pitches Bryce swings at in which counts. See, there is a very large differential in Bryce’s swing% in counts with no strikes between last year and this year, whereas in two-strike counts his swing% is about the same. He is taking more pitches when he has no strikes against him, especially the high fastball:

2015

Bryce Harper Swing% vs All Pitchers

Pitches: FA, FC, FT

Season: 2015-04-06 to 2015-10-04 | Count: 0 Strikes | Total Pitches: 611 | View: Catcher |

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

21 %

|

|

|

|

|

33 %

|

|

29 %

|

52 %

|

56 %

|

75 %

|

73 %

|

20 %

|

38 %

|

50 %

|

|

|

30 %

|

51 %

|

68 %

|

79 %

|

83 %

|

58 %

|

40 %

|

33 %

|

|

|

23 %

|

56 %

|

71 %

|

79 %

|

80 %

|

58 %

|

49 %

|

33 %

|

|

|

7 %

|

28 %

|

56 %

|

72 %

|

68 %

|

71 %

|

65 %

|

40 %

|

23 %

|

0 %

|

|

30 %

|

36 %

|

58 %

|

57 %

|

60 %

|

55 %

|

49 %

|

20 %

|

|

|

25 %

|

28 %

|

31 %

|

41 %

|

45 %

|

40 %

|

32 %

|

18 %

|

|

|

8 %

|

21 %

|

27 %

|

27 %

|

35 %

|

31 %

|

24 %

|

15 %

|

|

|

9 %

|

9 %

|

21 %

|

17 %

|

15 %

|

16 %

|

11 %

|

14 %

|

|

|

3 %

|

|

|

|

8 %

|

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

2016

Bryce Harper Swing% vs R

Pitches: FA, FC, FT

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-28 | Count: 0 Strikes | Total Pitches: 301 | View: Catcher |

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

5 %

|

14 %

|

24 %

|

19 %

|

43 %

|

38 %

|

13 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

22 %

|

28 %

|

39 %

|

38 %

|

61 %

|

35 %

|

10 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

20 %

|

46 %

|

55 %

|

44 %

|

68 %

|

64 %

|

32 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

11 %

|

25 %

|

43 %

|

58 %

|

53 %

|

51 %

|

70 %

|

55 %

|

27 %

|

0 %

|

|

24 %

|

39 %

|

45 %

|

50 %

|

58 %

|

55 %

|

31 %

|

17 %

|

|

|

18 %

|

42 %

|

40 %

|

41 %

|

55 %

|

39 %

|

7 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

7 %

|

34 %

|

44 %

|

50 %

|

42 %

|

26 %

|

5 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

0 %

|

15 %

|

29 %

|

36 %

|

48 %

|

17 %

|

7 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

He seems to be swinging at less pitches overall, and his focus has shifted from the top of the zone to the inside part of the zone. It should be noted, too, that he is swinging significantly less at breaking pitches with no strikes as well, which highlights something that’s a little less tangible. With fastballs the narrative becomes this: Bryce is taking more fastballs early in the count, which means he isn’t capitalizing on those fastballs. Once he has two strikes on him, it would reason to guess that he would have more trouble making square contact, right? Well, not quite…

Against fastballs in two-strike counts Bryce is actually hitting decently, but he’s still missing the ones across the middle of the plate. One thing I noticed is that, in two-strike counts, he’s getting thrown more breaking pitches than before, and less fastballs. In 2015, 258 out of 719 two-strike pitches were breaking balls (36%). In 2016, the mark has been 189 out of 448 (42%). With two-strike pitches in 2015, 383 out of 719 were fastballs (53%), whereas 2016 has only seen 220 out of 448 (49%). Bryce has become more aware of the outside pitches, both fastballs and breaking balls, and this has something to do with it.

With two strikes, Bryce is swinging at around the same rate in 2016 as he was in 2015. The pitches he is hitting successfully are: High and inside fastballs, away fastballs, away breaking pitches from righties, all breaking pitches in the middle of the plate, and high and inside breaking pitches from lefties. Ok, that’s pretty tedious. Let’s show all of that visually, looking just at 2016:

First, fastballs with two strikes

Bryce Harper SLG/P vs All Pitchers

Pitches: FA, FC, FT

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-29 | Count: 2 Strikes | Total Pitches: 220 | View: Catcher |

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.400

|

.400

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.333

|

.190

|

.000

|

.000

|

.143

|

.889

|

.667

|

|

|

.138

|

.258

|

.500

|

.114

|

.000

|

.000

|

.182

|

.250

|

|

|

.000

|

.195

|

.360

|

.209

|

.147

|

.000

|

.045

|

.071

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

.261

|

.242

|

.189

|

.093

|

.038

|

.038

|

.125

|

.045

|

|

|

.226

|

.182

|

.211

|

.179

|

.040

|

.000

|

.050

|

.045

|

|

|

.050

|

.077

|

.225

|

.720

|

.294

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.048

|

.300

|

.471

|

.111

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

Again, he’s gearing up for away pitches, and he’s swinging at almost anything, so he has success against away fastballs. We know that he’s been very keen on high and inside pitches of all kinds and in all counts this year, and that is also the easiest pitch to see. He has a reactionary eye for that pitch, and is able to catch up and drive it. High fastballs out over the plate can be somewhat easy to react to but he a) isn’t as keen on hitting them, b) isn’t seeing them that often in two-strike counts anyways, and c) isn’t expecting them. Thus, he’s most likely popping them up, which explains his high increased infield fly ball%. This is supported by the fact that his ground-ball rates on high fastballs with two strikes is quite low:

Bryce Harper GB/P vs All Pitchers

Pitches: FA, FC, FT

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-29 | Count: 2 Strikes | Total Pitches: 220 | View: Catcher |

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

11 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

17 %

|

6 %

|

0 %

|

3 %

|

8 %

|

8 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

0 %

|

12 %

|

14 %

|

5 %

|

9 %

|

25 %

|

36 %

|

21 %

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

|

13 %

|

16 %

|

11 %

|

14 %

|

31 %

|

35 %

|

31 %

|

9 %

|

|

|

3 %

|

7 %

|

11 %

|

11 %

|

28 %

|

22 %

|

15 %

|

9 %

|

|

|

0 %

|

3 %

|

13 %

|

24 %

|

24 %

|

24 %

|

5 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

0 %

|

0 %

|

5 %

|

15 %

|

29 %

|

22 %

|

7 %

|

0 %

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

|

|

|

|

0 %

|

Next, let’s look at slugging% against breaking pitches from righties with two strikes

Bryce Harper SLG/P vs R

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-29 | Count: 2 Strikes | Total Pitches: 126 | View: Catcher |

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

1.000

|

1.000

|

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.333

|

.600

|

.714

|

.500

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.091

|

.357

|

.429

|

.250

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.200

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.063

|

.167

|

.125

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.077

|

.059

|

.190

|

.308

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.444

|

.143

|

.310

|

.294

|

.593

|

.500

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.625

|

.313

|

.286

|

.656

|

.310

|

.286

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.143

|

.133

|

.083

|

.200

|

.263

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.045

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

Again, it appears that because the ball is curving towards him it’s going to be easier to drive. He is then able to pull the breaking pitches that are up and out over the plate, and is able to drive the low and outside pitches with authority. His lack of success on up and away pitches is a little perplexing, but could be attributed to anything from bad luck, to him possibly not seeing that exact pitch as well, to the fact that the sample size here is pretty small and he hasn’t seen a ton of pitches in that area.

Finally, let’s check out breaking pitches from lefties

Bryce Harper SLG/P vs L

Pitches: CH, CU, SL

Season: 2016-04-04 to 2016-07-29 | Count: 2 Strikes | Total Pitches: 63 | View: Catcher |

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

1.000

|

1.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.333

|

.800

|

1.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

1.000

|

2.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.167

|

.500

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.286

|

1.333

|

.667

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.400

|

.222

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

.000

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

.000

|

|

|

|

|

.000

|

Nothing monumental in this aspect, especially as it’s not too different from how he hits breaking pitches against lefties in all counts. Regardless, it still fits our narrative as the up and inside pitches are right in his wheelhouse, and the pitches that breaking out over the plate are easier to hit than any other breaking pitch coming from a lefty.

Whew. That is a lot of heat maps to take in. Let’s review a bit: Bryce has a tendency to take more pitches early in the count, something he hasn’t done before. He’s also opening up, which makes him susceptible to breaking pitches and causing him to make weaker contact. The fact that he’s making more contact on pitches outside of the zone doesn’t help much either. He’s taking more fastballs as well, and once he has two strikes on him he’s seeing less of them, and is most likely expecting them less. He then begins to swing much more frequently, which actually reaps pretty good rewards, though there are some holes in his swing against certain pitches. He can’t get the high fastball, and struggles with breaking pitches against lefties. The result of all of this? Lower BABIP, lower wRC+, lower wOBA, you name it.

Obviously there are factors involved with this that go far beyond what heat maps and stats can show us. Baseball is an incredibly mental game, and once you realize you’re in a slump it can sometimes just drive you deeper into that slump. Statistics also can almost never tell the whole story, and as I mentioned earlier the sample size here is small enough that none of this is much of a predictor for future behavior. There’s a good chance that, on many of the situations mentioned above, Bryce has just gotten unlucky (or heck, maybe even lucky) and thus the heat map doesn’t reveal much. Overall though, when looking at everything in a holistic manner it allows us to construct an idea as to why Bryce is failing where he previously succeeded. We can never know everything for sure, but we know more than we did.

I’ve been hearing for months now that Bryce will be just fine, slumps happen to everyone, he will soon return to form, etc., and I’m not here to disagree with that. Although, I will ask (and I ought add that I am a big supporter of Bryce’s): What if he doesn’t break out of it? Odds are his 2015 will be one of the best seasons of his career, and 2016 (if it continues like this) will be one of his worst, and he will find himself somewhere in between for the rest of his career. It’s just that the deeper he drives himself into this rut the more compelled I am to find the source of problem as best I can, from a purely analytical standpoint.

Love him or hate him, the more that Bryce (and the many young superstars like him) thrives, the more baseball thrives.

(Note: All statistics and heat maps taken from Bryce’s page on FanGraphs.com)