The Julio Teheran Delivery Mystery

It’s hard, sometimes, to believe that Atlanta Braves pitcher Julio Teheran is only 26. After being signed out of Colombia in 2007, Teheran got his first sniff of the majors as a 20(!) year-old four years later, then ranked as the second-best pitching prospect in the league. As a mid-rotation starter in 2013, Teheran more than justified that ranking, putting up a 3.69 FIP, 22 K%, 2.5 WAR season for a 98-win Braves team that would ultimately fall to the Dodgers in the NLDS.

That Braves team was still an exceptional one; the next few Braves teams (winning 79, 67, and 68 games) less so. For that reason, when Teheran has been mentioned recently, it’s often been in reference to his status as a potential trade chip. It’s no secret that the Braves are in full-fledged rebuilding mode, and a good, young pitcher with over three years left of reasonably-priced team control ($6.3M this year, followed by $8M, $11M, and $12M) could fetch an enticing package of prospects to add to their growing collection.

There’s just one problem – Teheran’s currently in the middle of the worst year of his career, and, even worse, he’s the not-so-proud owner of some of the least favorable pitching statistics in the majors. His 5.67 FIP, far higher than his 3.69 figure last season, is seventh-worst among qualified starters, and his -0.3 WAR ranks fifth from the bottom. As you might assume from the preceding figures, Teheran’s rate statistics have been similarly ugly. In fact, as the following chart illustrates, the sum of Teheran’s decline in K% and increase in BB% from 2016 to 2017 (9.5%) is the fourth-highest among all pitchers who qualified in both years.

| Pitcher |

Dec. in K%

|

Inc. in BB%

|

Total

|

| Kevin Gausman | 8.8% | 4.0% | 12.8% |

| Justin Verlander | 7.4% | 5.3% | 12.7% |

| Jeremy Hellickson | 9.8% | 1.1% | 10.9% |

| Julio Teheran | 5.7% | 3.8% | 9.5% |

| Zach Davies | 4.2% | 2.4% | 6.6% |

| R.A. Dickey | 4.1% | 1.1% | 5.2% |

| Wade Miley | -0.4% | 5.3% | 4.9% |

| Jaime Garcia | 2.8% | 1.4% | 4.2% |

| Jerad Eickhoff | 0.9% | 3.2% | 4.1% |

| Ervin Santana | 1.5% | 2.1% | 3.6% |

| Jason Hammel | 3.6% | -0.2% | 3.4% |

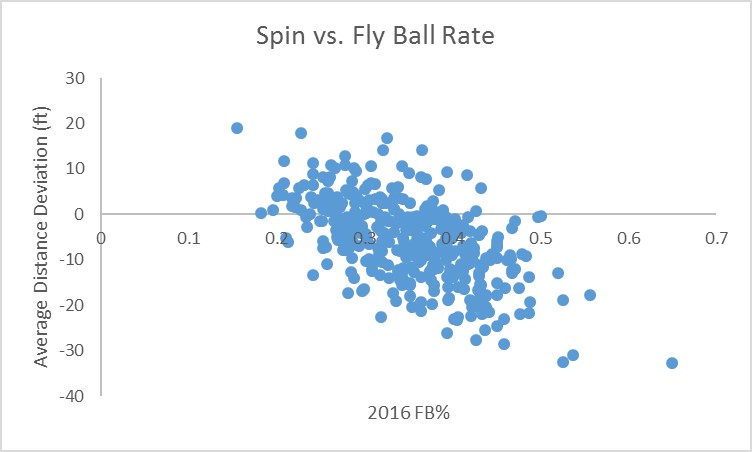

Overall, Teheran’s K% has fallen from 22% to 16.3%, his BB% has ballooned from 5.4% to 9.2%, and while his fly-ball rate isn’t significantly higher (although it is the fifteenth-highest in the majors), his HR/FB rate is up nearly five percentage points. In some circumstances, such an increase in HR/FB% might lead one to believe that, to an extent, the pitcher in question has simply been unlucky. But Teheran’s HR/FB rate, at a shade over 15%, isn’t unreasonably high; it’s in approximately the 63rd percentile in the league. And it’d be hard to chalk up such a dramatic shift in both strikeout and walk percentages solely to random misfortune.

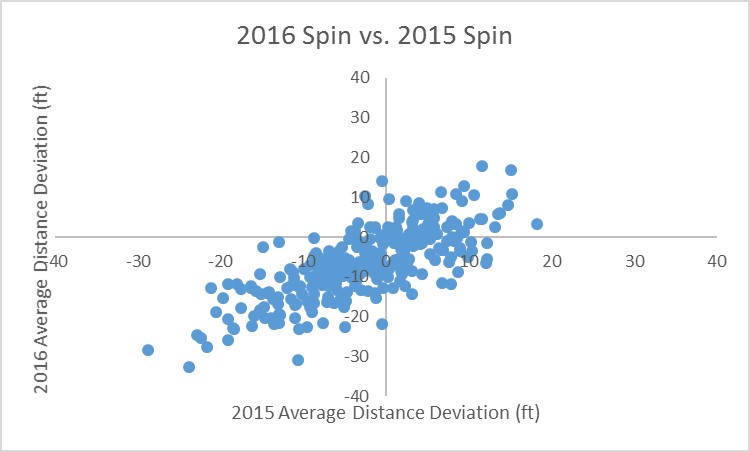

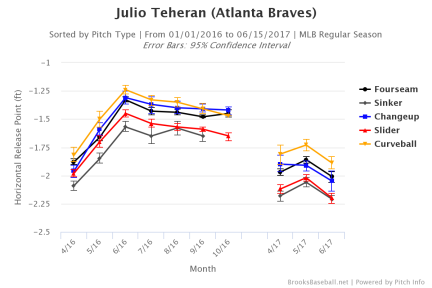

There doesn’t appear to be a significant difference in any of Teheran’s pitches this year, either in velocity or movement, that would explain his sudden loss of effectiveness. Additionally, none of his pitches’ spin rates have declined this year (although his slider’s spin rate has actually increased by over 200 RPM). There has, however, been an interesting development this season in regard to Teheran’s mechanics. Look at the dramatic change in his horizontal release point:

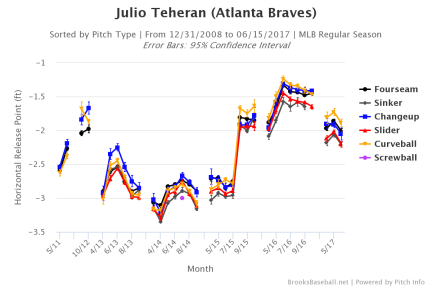

It’s evident that Teheran consciously changed his delivery during the offseason, at least with respect to his horizontal release point (his vertical release point didn’t change nearly as dramatically). And this isn’t the first time he’s switched up his mechanics; when we expand the x-axis even farther, we can see just how much Teheran has tinkered with his horizontal release throughout his career.

We can see that, compared to today, Teheran had a similar horizontal release point between August 2015 and May 2016. His results during that time span were excellent – a 2.86 ERA (although his FIP was a full run higher), a 21.4 K%, and a 7.4 BB%. But Teheran’s abrupt midseason change in horizontal release point last season didn’t seem to negatively impact his performance afterwards. From June to October 2016, his FIP and BB% were both lower, and his K% was slightly higher, than they were before he altered his delivery.

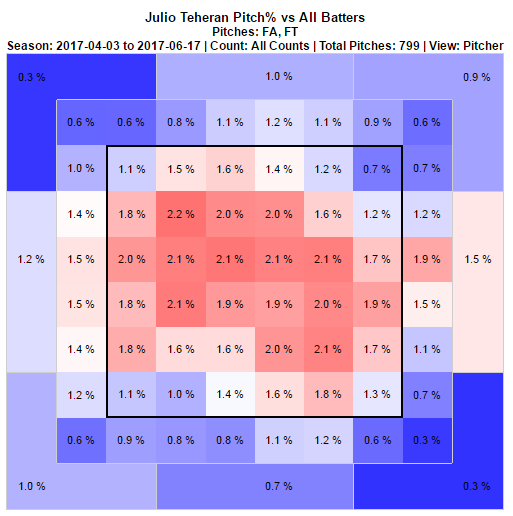

This naturally raises the question: if Teheran was so successful during the second half of 2016, why did he change his delivery so radically over the offseason? It’s probably premature to say that Teheran’s change in delivery is necessarily the cause of his struggles this year, but there could, at least theoretically, be some secondary consequence of his new mechanics that’d explain his lackluster performance. A potential clue might lie in Teheran’s swinging strike rate, which has declined from around 10.5% – where it’s consistently been throughout his career – to 8.4% this season, despite him throwing a similar percentage of his pitches for strikes in 2017 as in years prior. To me, this could suggest that something in Teheran’s delivery is leading batters to more easily pick up on his pitches’ trajectory. It’s also possible that the mechanical change has affected his control. Although Teheran’s thrown about five percent more fastballs this year, these pitches have been far more spread out across the strike zone in 2017, as the following graph illustrates (see here for 2016):

I’m not particularly privy to the Braves’ everyday clubhouse conversations, but it’d be hard to believe that an adjustment this large didn’t come from Atlanta’s coaching staff. I can think of a few possible explanations behind the change: (1) the belief that Teheran’s old delivery would increase injury risk, (2) the belief that Teheran’s velocity, movement, or command would improve with an altered delivery; or (3) a combination of the two. We can’t know for sure – and we can’t definitively confirm a link between Teheran’s new mechanics and his depressed performance – but I’d say this is a situation worth keeping an eye on, especially as the trading deadline approaches. It’ll be interesting to see if Teheran and the Braves coaching staff continue to tinker with the young right-hander’s delivery, especially if he continues to struggle so much over the coming weeks.