98.4 percent is pretty good odds, correct? According to Baseball Prospectus, those are the current odds that the Houston Astros win the American League West. Houston has dominated the headlines and other teams thus far in the MLB season. The ‘Stros are 42-18, and 12 games up on the .500 Seattle Mariners, who are in second place. It looks like a lock that the Astros are going to win the AL West. I am here to explain to you how the Seattle Mariners can overtake the Astros. Let’s start by analyzing how some of the most important Astros may be due for regression.

Jose Altuve

Altuve is a flat-out stud, and looks to be well on his way to a fourth straight 4-WAR season. There is not that much to worry about looking at his stats this year, but I am going to nitpick. Altuve’s BB/K rate has plummeted this season to the lowest point in his career at 0.61, which is .25 lower than his mark a year ago. Also, take a look at his power numbers relative to some percentages over the last few years.

|

Home Runs |

Pull% |

Soft% |

GB% |

| 2013 |

5 |

32.9 |

13.4 |

.49 |

| 2014 |

7 |

41.8 |

17.9 |

.48 |

| 2015 |

15 |

45.3 |

19.8 |

.47 |

| 2016 |

24 |

45.3 |

13.6 |

.42 |

| 2017 |

8 |

39.6 |

18.8 |

.53 |

Altuve is on pace for about the same amount of home runs as his career high 24 last year, but some numbers point to him hitting fewer balls out of the ballpark. Generally, those who pull the ball have more power, as has been the case with Altuve. This year though, Jose is pulling the ball much less, and is having more soft contact than any full year of his career other than 2015. Also, Jose is hitting a lot more ground balls, a sign of fewer home runs, which so far has not been the case. Additionally, it is not like the second baseman’s average is up with the decrease in fly balls, as it is down 12 points from a year ago. Not only is his average lower, but his BABIP is higher than it has been at any point in his career, a sign of luck. Jose is known for his ability to make contact at nearly anything, but his contact rate his dropped significantly to the lowest point in his career at 84.5%. Lastly, while a quick player, Altuve has been a below-average fielder as far as range is concerned over his career with the exception of 2015. This year, it looks a little unsustainable that his range runs above average is positive.

George Springer

Springer has had a very solid season thus far for Houston, and I had some trouble finding a reason not to believe it will not continue. I soon came across one stat that was very telling. Springer is on pace for over 43 home runs, which would shatter his career high. He is hitting about the same amount of ground balls, liners and fly balls, but his home run/fly-ball rate is an absurd 31.4%. Expect that to normalize and some of those wall-scrapers to be warning-track shots. Also, while a player can improve defensively, they usually do not improve as much as Springer has thus far this year. His UZR/150 in 2017 is almost twice as high as it ever has been in his career.

Carlos Correa

Correa has always been a player loaded with potential, drawing comparisons to Alex Rodriguez. Correa has lived up those expectations for the most part this season, but some of that may be due to luck. His BABIP is very high at .353, 30 points above his career average. Correa defensively has been interesting as well and has been better this year, but it may be unsustainable. The Houston shortstop has been below average as far as errors committed are concerned, but has shot up to above average this season.

Dallas Keuchel

The former Cy Young award winner has other-worldly stats this year. Keuchel was unlucky last year, but appears to be getting a little lucky this year. His ERA is an insane 1.67, but his FIP, a better measure of run prevention, is a much more realistic 3.02. His Left on Base rate is also much higher than it has been at 88.8, a tenth of a percent out of the highest in the majors. Both of these stats indicate luck. Another statistic that does the same is BABIP. Obviously Keuchel is inducing more weak contact this year, but not normally enough for his BABIP to drop over 80 points from a year ago.

Mike Fiers

Upon first glance, Mike Fiers has not a good season, with an ERA in the high-4s. Further research, though, makes it clear that his 2017 campaign may be getting a lot worse soon. His FIP is at a massive 6.53, the second-highest in all of baseball. Also, his BABIP is just .289, over 30 points lower than last year, leading us to think he is not getting that unlucky as far as balls dropping in that would not normally be hits. Fiers’s LOB% is higher than it has been in any full MLB season for him at 86.0 %. The veteran right-hander has had a bad year, but it could get worse soon.

—–

Now let’s take a look at the Seattle Mariners. I actually picked the M’s to win the west preseason (I hope I did not just lose all my credibility). I’ll highlight five players in Seattle that could lead to some success in the Pacific Northwest.

Robinson Cano

The M’s simply will not succeed unless Cano is phenomenal. And while he has been good this year, there are some signs that could point to him being better. His walk rate and strikeout rate are both the best they have been since 2014. That combined with his highest hard-hit percentage of his career, should point to great offensive success. More good news for Cano comes when you look at his O-Swing%, as it is down from a year ago, meaning he is swinging at fewer balls. His contact rate too is the highest it has been since 2014. His BABIP is also the lowest it has been in his entire career, majors and minors included.

Kyle Seager

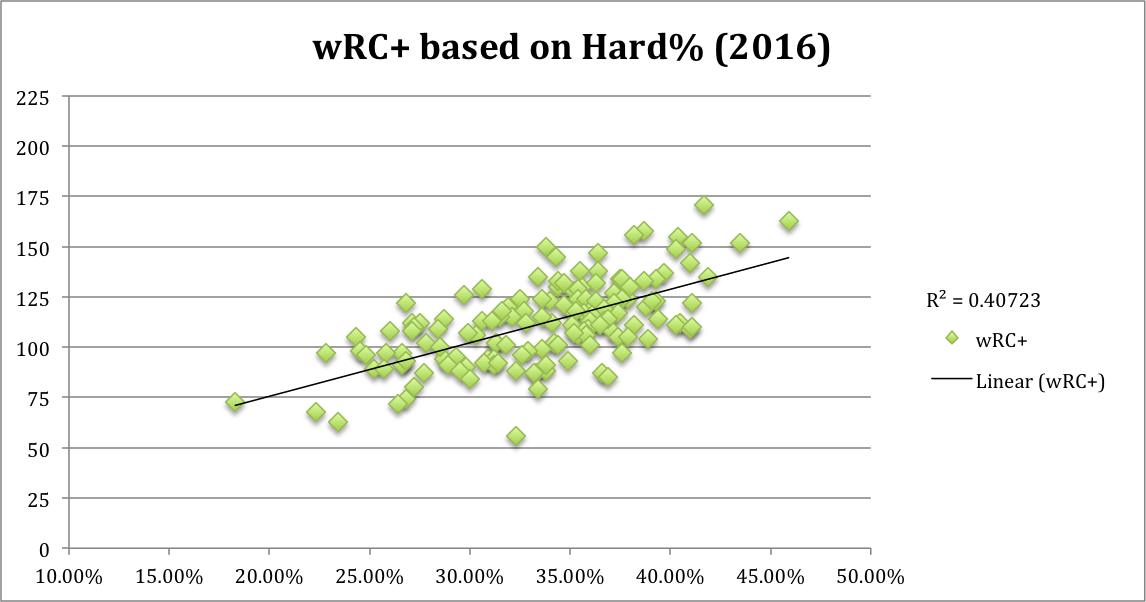

The Mariner third baseman has been one of the most consistent players in the majors, and had a career year in 2016. This year, though, he is struggling a little bit. His wRC+, a measure of how productive a player is relative to league average, is the lowest it has been since his rookie year. Seager’s baserunning this year has been the worst of his career already, as measure by UBR. This, like defense, is something that is subject to skewed numbers in small sample sizes, and his baserunning should improve to around league average. Another reason for optimism is Seager’s HR/FB%. It has dropped all the way to 8.5%, over 6% lower than last year. Also, his BB% is the same as it was last year, but it should soon rise as evident by his O-Swing%. Seager is swinging at by far the fewest amount of balls outside the strike zone in his career.

James Paxton

Time to brag. I picked Paxton to be in the top three of AL Cy Young voting this year. He has been injured, but him coming back for this Mariner club, and I want to explain just how dominant he has been and is capable of being. He has reached 2.0 WAR in just 48 innings this year. His FIP and ERA are both sub-2, a sign that this success is not all due to luck. His WHIP, a good indicator of future success is the lowest it has been in any full season of his. His Hard% is the lowest of his career, and Paxton’s LD% is by far the lowest it has ever been. To do that with his uptick in velocity is very impressive. Speaking of the rise in velocity, he has been able to keep relatively the same speed on his changeup, increasing the discrepancy between the speed of the pitches. Paxton has all the ability to perform like a true ace the rest of the way.

Felix Hernandez

Hernandez will be coming back soon from injury, but has not performed up to standards of one affectionately called ‘The King.’ There are reasons to think he may turn it around though. He is throwing a greater percentage of strikes than he ever has. The main portion of those pitches thrown are fastballs, and while his fastball velocity is down from his career average, it is up from last year. There are some signs of bad luck too, as his HR/FB% is by far the highest it has ever been, while he’s still inducing fewer hard-hit balls than a year ago. Also, his xFIP is well over a run lower than his actual ERA. Felix may not be the King that accumulated 5.8 WAR a year for a six-year span anymore, but he can still be very effective.

Yovani Gallardo

Gallardo is now on his fourth team in four years, and is having the worst statistical season of that span. His ERA is over six, which obviously is a cause for concern, but his xFIP is in the mid-fours. His HR/FB% is the highest of his career, and his BABIP is the second-highest it has ever been. Additionally, his LOB% is the lowest it has ever been. His stuff is not all bad, though, as his fastball in over 2 MPH faster than it was a year ago. He is also inducing the most swing-and-misses since 2012.