Tommy Joseph Learns the Value of Patience

While Phillies first-base prospect Rhys Hoskins spent April on the Triple-A leaderboards, his big-league counterpart, Tommy Joseph, was among the least productive everyday players in the majors. Through the first month of the season, Joseph hit for a dreadful .179/.222/.254 slash line, along with a .211 wOBA and 25 wRC+. While a BABIP of .234 didn’t do him any favors, Joseph’s 27.8 K% and 5.6 BB% suggested that the 26-year old was simply being outmatched at the plate. All in all, despite passable defense at first base, Joseph’s lack of offensive output was enough for him to accumulate -0.7 WAR, tied for the third-lowest in the league.

It didn’t take long for the local media to start calling for Joseph’s spot in the starting lineup. Hoskins, who Eric Longenhagen rated in February as the Phillies’ ninth-best prospect, ended the month with six home runs and a .338 batting average — numbers that look even better when compared to Joseph’s disappointing output. By the last week of April, some Phillies writers were suggesting promoting Hoskins to the big-league starting lineup in favor of Joseph. Even the sports section of the city’s largest newspaper demanded the team make the switch. As longtime Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Bob Brookover wrote in the first week of May, Hoskins “[c]utting into Joseph’s playing time when he’s hitting below the Mendoza Line would not cause nearly as much turmoil as [Joseph cutting into Ryan Howard’s playing time] did a year ago.”

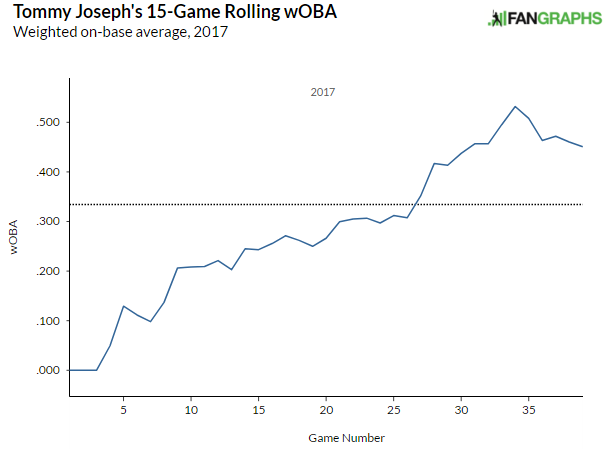

Since the beginning of May, though, the cries to replace Joseph in the lineup have, for the most part, been quieting down. This trend can be attributed to the fact that, surprisingly enough, Tommy Joseph has been one of Major League Baseball’s best hitters this month. Since the beginning of May, Joseph’s 185 wRC+, .459 wOBA, and .344 ISO rank eighth, eighth, and twelfth, respectively, among nearly two hundred qualifying batters. Take a look at how drastically his rolling wOBA has shifted throughout the first two months of the season:

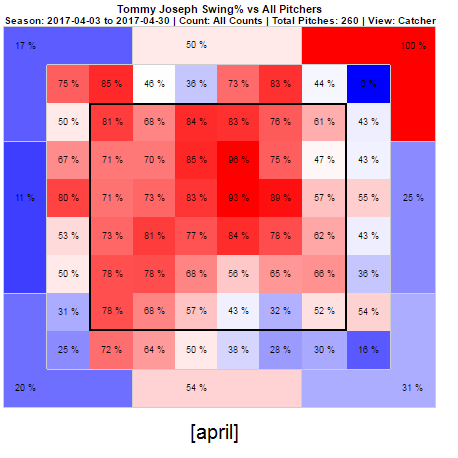

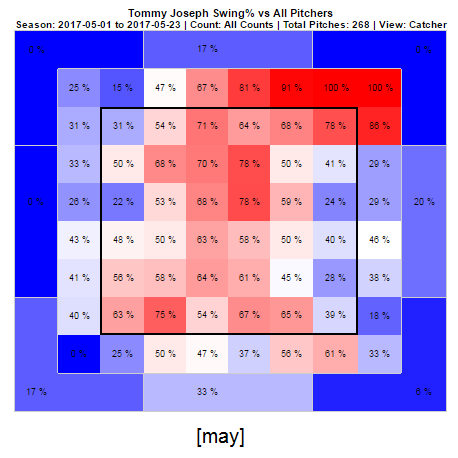

Among qualifying batters, Joseph’s improvement in wOBA from April to May was the largest such increase in the league. Such a change seems unlikely to organically occur, although luck certainly can play a part (I would be remiss not to mention Joseph’s .390 May BABIP). I expect, however, that there’s a more concrete explanation for Joseph’s recent success. It doesn’t take a very long look at Joseph’s numbers to get an idea of how he altered his approach. Put simply, Joseph stopped swinging at everything in and around the strike zone. Compare the following two heat maps, one from April and one from May:

On April 30, Tommy Joseph had an O-Swing%, Z-Swing%, and overall Swing% of 38.8, 78.8, and 56.2, respectively. If those percentages sound high, it’s because they are; they ranked eighth, fifteenth, and eighth highest in the majors. May, on the other hand, has been a different story. While Joseph has still been chasing up-and-away pitches, he’s become far more adept at laying off of pitches on the inner half of the plate (even though he’s seen ten percent fewer fastballs), and has cut down his swinging rate in virtually every other section of the strike zone. With a May O-Swing% of 27.2, Z-Swing% of 63.9, and Swing% of 41.9, one of the majors’ most free-swinging hitters has been playing like one who, while not exactly Joey Votto, is far less extreme, relative to the rest of the league, than he was in April.

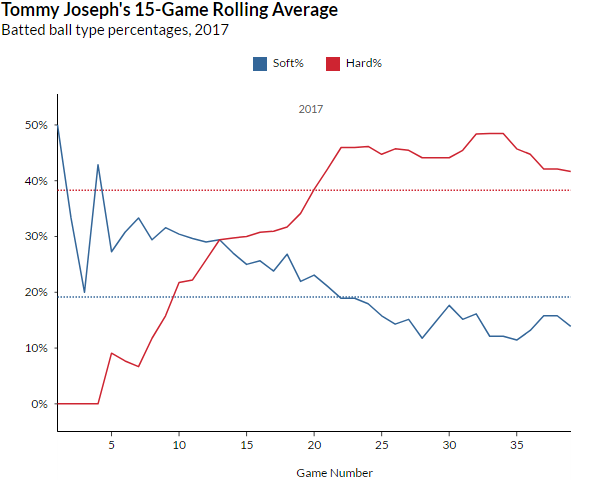

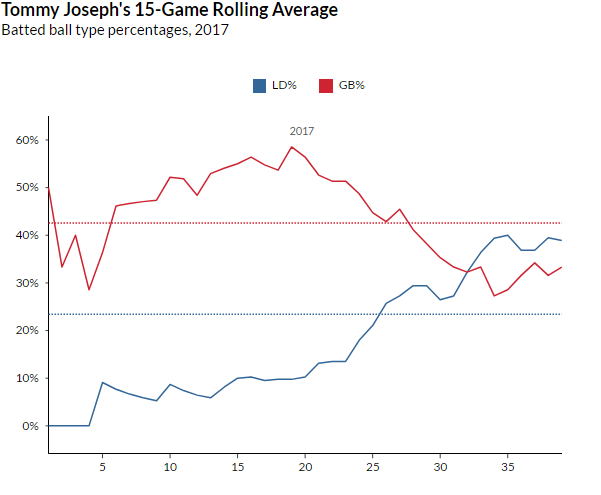

Interestingly, Joseph’s contact rates haven’t significantly changed since he started taking a more patient approach at the plate. We would, however, expect an improvement in the quality of his contact. His hard- and soft-hit percentages have trended in opposite directions since the beginning of the month, as have his line drive and ground ball rates:

While Joseph’s improvements must be encouraging for a Phillies team that has struggled mightily as of late, it’s still hard to imagine Tommy Joseph being a key contributor on the next contending Phillies team. As mentioned earlier, Joseph has had a .390 BABIP this month, and, even with his more refined approach at the dish, his 22.5 K% and 9.9 BB% in May shouldn’t exactly reassure anyone that he’s anything more than a solid placeholder while the team rebuilds. If Joseph can continue exhibiting patience at the plate, though, he might just put up numbers impressive enough to curb the antsiness of the more impatient members of the Philadelphia fandom. Phillies supporters shouldn’t necessarily give up on the idea that Rhys Hoskins, if he keeps mashing in Triple-A, could reach the majors this year — especially if Joseph gets injured — but as a rebuilding team, the Phillies have no need to rush any of their promising young prospects to Philadelphia. And if Joseph’s discipline changes are for real, they might find themselves with a better placeholder at first base than they may have been expecting.