Bucking the Trends

As Cubs fans and non-Cubs fans alike celebrate the end of the 108-year drought, we have overlooked the fact that in winning, the Cubs also bucked two trends in major league baseball:

- 100+ win teams struggle in the postseason and rarely win the World Series, especially since the wild-card era began in 1995

- Losers of the ALCS and NLCS (Cubs lost 2015 NLCS) historically decline the following season, both in win total and playoff appearance/outcome

Below is a table to quantify a team’s performance in the playoffs:

|

Playoff Result |

Playoff Result Score |

| Win WS | 4 |

| Lose WS 4-3 | 3.75 |

| Lose WS 4-2 | 3.5 |

| Lose WS 4-1 | 3.25 |

| Lose WS 4-0 | 3 |

| Lose LCS 4-3 | 2.75 |

| Lose LCS 3-2* | 2.666666667 |

| Lose LCS 4-2 | 2.5 |

| Lose LCS 3-1* | 2.333333333 |

| Lose LCS 4-1 | 2.25 |

| Lose LCS 4-0 or 3-0* | 2 |

| Lose LDS 3-2 | 1.666666667 |

| Lose LDS 3-1 | 1.333333333 |

| Lose LDS 3-0 | 1 |

| Lose Wild Card Game | 0.5 |

| Miss Playoffs | 0 |

*The LCS was a best-of-five-game series from 1969 through 1984

It is important to acknowledge how close a team comes to winning a particular round. Based on a 0 to 4 scale, with 0 indicating the team missed the playoffs and 4 indicating the team won the World Series, the table credits fractions of a whole point for each playoff win. For example, in a best-of-seven-game series, each win (four wins needed to clinch) is worth 0.25. In a best-of-five-game series, each win (three wins needed to clinch) is worth 0.333 (1/3). Any mention of playoff result or average playoff result in this article is derived from this table.

THE STRUGGLE OF 100+ WIN TEAMS IN THE POST-SEASON

Playoff baseball, due to its small sample size and annual flair for the dramatic, historically has not treated exceptional regular season teams well. Jayson Stark recently wrote an article for ESPN titled, “Why superteams don’t win the World Series.” He noted that only twice in the first 21 seasons of the wild-card era had a team with the best record in baseball won the World Series (1998 and 2009 Yankees). Those two Yankee teams are also the only two 100-win ball clubs in the wild-card era to win the World Series. Research in this article will span the years 1969 to 2015, with 1969 being the first year of the league championship series (LCS).

Entering the 2016 season there had been 47 100+ win teams since the start of the 1969 season. Of those, 10 (21.3%) won the World Series. Other than those 10 World Series winners, how did 100+ win teams fare in the post-season?

Below are the average playoff results for 100+ win teams in each period of the major league baseball playoff structure from 1969 to 2015. The playoff structures were as follows:

1969-1984: LCS (best of 5 games) + World Series (best of 7 games)

1985-1993: LCS (best of 7 games) + World Series (best of 7 games)

1995-present: LDS (best of 5 games) + LCS (best of 7 games) + World Series (best of 7 games)

The wild-card game (2012-present) is omitted because a 100+ win team has yet to play in that game, although it certainly would be rare if we ever see a 100+ win team playing in the wild-card game.

| Teams | Average Playoff Result | WS Titles | % WS Titles | |

| 1969-1984 | 18 | 3.07 | 7 | 38.9% |

| 1985-1993 | 7 | 2.75 | 1 | 14.3% |

| 1995-2015 | 22 | 2.27 | 2 | 9.1% |

| 1969-2015 | 47 | 2.65 | 10 | 21.3% |

As the data shows, 100+ win teams during the 1969-1984 period on average made a World Series appearance. This could be partly due to the fact there was only one round of playoffs (the LCS) ahead of the World Series, with the LCS being a best of five games. It was certainly a much easier path to the World Series once a team made the playoffs, yet on average 100+ win teams were finishing with a World Series sweep.

Changing the LCS from a best-of-five-game series to a best-of-seven-game series had a negative impact on team post-season performance, as 100+ win teams during the 1985-1993 span on average lost a deciding Game Seven in the LCS.

When the league added the wild card and LDS in 1995, it expanded the opportunity to make the playoffs but made the path to a World Series title more difficult, for a team now had to win 11 games to hoist the trophy. In the wild-card era, 100+ win teams are on average losing 4-1 in the LCS. This period also has the lowest percentage of 100+ win teams winning the World Series.

| Average Playoff Result | Likelihood to Win WS | |

| 1969-1984 | 3.07 | 25.3% |

| 1985-1993 | 2.75 | 19.4% |

| 1995-2015 | 2.27 | 6.8% |

| 1969-2015 | 2.65 | 17.1% |

Using average playoff result standard deviation and a normal distribution, we can also see that the likelihood of a 100+ win team to win the World Series has had a significant decrease over the past several decades, left at under 7% during the wild-card era. The longevity of 100+ win teams in the playoffs has been trending downward over the past several decades. Despite being on the verge of a World Series defeat, the Cubs were able to successfully break through and buck a trend that had haunted outstanding regular-season teams for decades, especially since the wild-card era began in 1995.

THE CURSE OF THE LCS DEFEAT

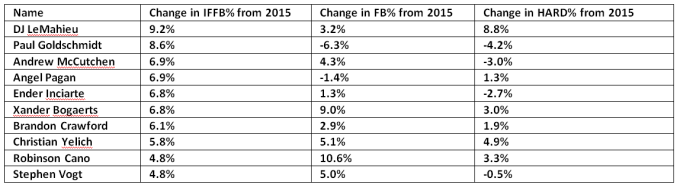

The 2015 Cubs lost to the Mets in the NLCS yet bounced back in 2016 to have an even better regular season and win the World Series. This, however, was a rare feat. Teams that lose in the LCS historically win fewer regular-season games and perform worse on average in the post-season (if they make it) the following year. Below are two charts (1969-2015 and 1995-2015) that display average win differential, average playoff result, likelihood win differential is greater than +5 (2016 Cubs were +6), and the likelihood of winning the World Series.

| 1969-2015 | American League | National League | MLB |

| Average Win Differential | -7.27 | -5.73 | -6.5 |

| Average Playoff Result | 1.02 | 1.07 | 1.05 |

| Likelihood Win Differential is >(+5) | 13.7% | 13.7% | 13.8% |

| Likelihood to Win WS | 2.9% | 2.7% | 2.8% |

| 1995-2015 | American League | National League | MLB |

| Average Win Differential | -5.42 | -2.32 | -3.87 |

| Average Playoff Result | 1.00 | 1.46 | 1.23 |

| Likelihood Win Differential is >(+5) | 18.1% | 21.6% | 20.0% |

| Likelihood To Win WS | 1.4% | 5.2% | 3.2% |

Due to the 1981 and 1994 strikes, a few data points for win differential and playoff result are not included in the calculation. The data set includes 82 LCS losers for win differential and 88 LCS losers for average playoff result. The 1980-81, 1981-82, 1993-94, 1994-95, 1995-96 win differentials are not included for LCS losers in both leagues. The 1994 and 1995 playoff results are not included for LCS losers in both leagues because there was no post-season in 1994, hence no LCS loser. Regardless, there is a notable trend among LCS losers to perform worse the following season.

The 2016 Cubs not only won six more regular-season games than in 2015, but they became only the seventh team in history to lose the LCS one season and win the World Series the following season (1971 Pirates, 1972 Athletics, 1985 Royals, 1992 Blue Jays, 2004 Red Sox, 2006 Cardinals). Two of the previous six teams repeated as champions: 1973 Athletics and 1993 Blue Jays. Most recently, the 2005 Red Sox lost 3-0 in the ALDS and the 2007 Cardinals failed to make the playoffs.

LOOKING FORWARD

The Cubs have already been pegged favorites to win the 2017 World Series, which isn’t surprising given the fact nearly every key player is under team control. Is history on their side? Winning back-to-back titles is difficult in today’s competitive league, as new baseball thinking has somewhat evened the playing field and the small sample size of post-season baseball has the ability to lend unexpected results.

The 10 100+ win teams who have won the World Series since 1969 historically have not been successful in their attempts for back-to-back titles. Below are the average win differentials and average playoff result for these teams in the season following their championship:

| Win Differential From 100+ Win WS Team | Playoff Result | |

| 1970 Mets | -17 | 0 |

| 1971 Orioles | -7 | 3.75 |

| 1976 Reds | -6 | 4 |

| 1977 Reds | -14 | 0 |

| 1978 Yankees | 0 | 4 |

| 1979 Yankees | -11 | 0 |

| 1985 Tigers | -20 | 0 |

| 1987 Mets | -16 | 0 |

| 1999 Yankees | -16 | 4 |

| 2010 Yankees | -8 | 2.5 |

| Average | -11.5 | 1.83 |

Only three of these 10 teams (1975-76 Reds, 1977-78 Yankees, 1998-99 Yankees) have repeated as champions. Can the 2017 Cubs be the fourth? No matter the numbers, the 2017 Cubs still have to perform on the field. They were on the brink of losing the World Series in 2016, so we must not take anything for granted. But despite this, there’s no doubt the 2017 Cubs will be in a good position for a repeat. The Cubs are expected to be MLB’s best regular season team in 2017, according to FanGraphs and Jeff Sullivan’s analysis in his November 11, 2016 article. Only time will tell.