Austin Jackson’s Bothersome Batted-Ball Bind

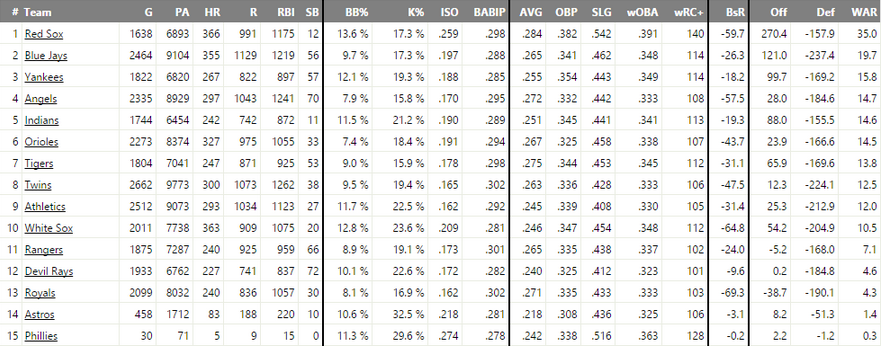

On July 30, 2014, the Seattle Mariners found themselves in the interesting position of being in playoff contention. The Mariners sported a 32-23 record, only 2.5 games back of the AL West-leading Los Angeles Angels, and owned the third-best Pythagorean record in the American League. Seattle’s newfound position as postseason hopefuls meant that they were suddenly buyers at the trade deadline – not drastically so, but in the sense that the Mariners were only a couple of upgrades away from assembling themselves a nicely well-rounded playoffs roster. Chief among these desired upgrades was a serviceable everyday center fielder, one who could replace a revolving door of below-average outfielders that included Abraham Almonte, James Jones, Stefen Romero, and Endy Chavez.

Jack Zduriencik sought to remedy the Mariners’ outfield issues with a pair of trade deadline deals. The first involved packaging Almonte and minor-league pitcher Stephen Kohlscheen to the Padres in return for Chris Denorfia, a rather unsexy deal to be sure, but one that was a success at the time in that the acquired player was not Almonte. The second deal, a three-way transaction between the Rays, Tigers, and Mariners, was collectively more sexy, but a large share of the sexy went to the Tigers, who landed Rays ace David Price. The other major components of the deal were the Rays’ acquisition of young Mariners middle infielder Nick Franklin and Tigers pitcher Drew Smyly, as well as Seattle’s prospective answer to its outfield problem: Detroit center fielder Austin Jackson.

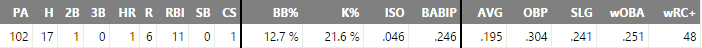

Since his move to the Mariners, Jackson has racked up 277 plate appearances for Seattle, and the results have been fantastically underwhelming. Of the center fielders who amassed more than 100 plate appearances for the Mariners in 2014 – an uninspiring triumvirate of Jackson, Abraham Almonte, and James Jones – Jackson produced the worst offensive performance by wRC+. Jackson’s 2014 performance also disappointed even by more conventional measures:

- Jackson totaled 34 extra-base hits in 416 plate appearances for the Tigers in 2014. For the rest of the year, in 240 plate appearances for the Mariners, Jackson managed 6.

- Jackson’s ISO dropped from .127 to a paltry .031 with the move from Detroit to Seattle.

- Jackson’s 2014 OBP/SLG/wOBA with Detroit: .330/.397/.321. With Seattle: .271/.264/.243.

Not great for a player only two seasons removed from a 5-win campaign.

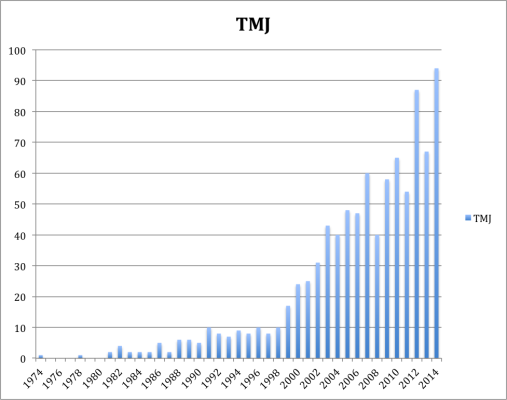

Ostensibly, something was fundamentally different with Jackson in 2014, something that can hopefully be determined by closely examining his recent performance. Looking first to Jackson’s approach, it seems that there hasn’t been too much change over the course of his career. His K/BB ratio has generally hovered around league average and his contact rates haven’t fluctuated all that much from year-to-year. If anything, Jackson’s approach metrics look like they’re trending positively – he actually posted career bests in Z-contact% and SwStr% in 2014. If we examine Jackson’s batted ball data, however, we begin to get a little closer to the root of Jackson’s troubles of late. The most easily identifiable aspect of Jackson’s game can be somewhat distilled in the following graphic:

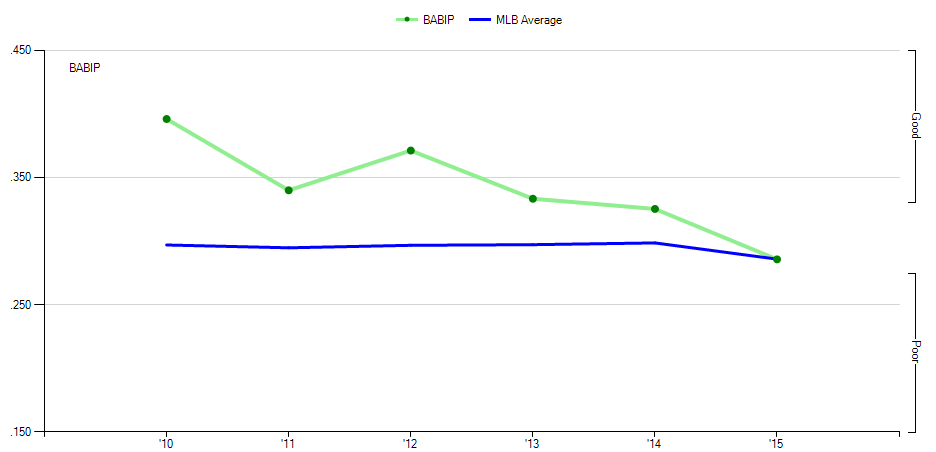

Over the course of his career, Jackson’s BABIP has been way above league average. He managed an absolutely ridiculous .396 BABIP in his 2010 rookie season over 675 PA, and his career-best 2012 season, in which he posted a 134 wRC+, was bolstered by a BABIP of .371. That figure would predictably fall after 2012, but between 2013 & 2014, Jackson’s BABIP only declined by .008, whereas in the same period, his wOBA fell from a very good .332 to a mediocre .292. This might suggest that in 2014 specifically, it may not have been the frequency with which Jackson was able to put balls in play so much as the quality of those batted balls that limited Jackson’s production.

Unfortunately, batted ball data is out of the scope of my access. The closest I can get to Jackson’s batted-ball profile is by pulling data from this pre-season piece on Jackson by Jake Mailhot over at Lookout Landing, and indirectly from Jeff Zimmerman’s work on hitter analytics at RotoGraphs (the relevant batted-ball spreadsheet now seems to be unavailable for some reason).

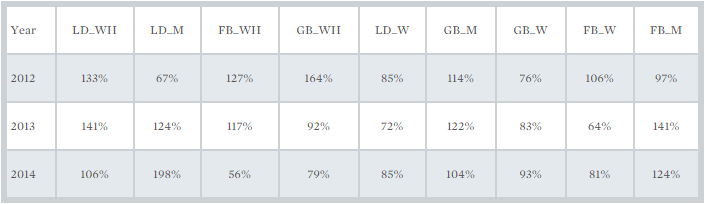

To quickly explain – this table charts batted-ball rates expressed as a percentage of league average. Batted balls are separated into three categories (line drive, groundball, fly ball) which are then further divided into subcategories of contact quality (Well-Hit, Medium, and Weakly-hit). These categories are ordered left-to-right from highest to lowest based on xBABIP.

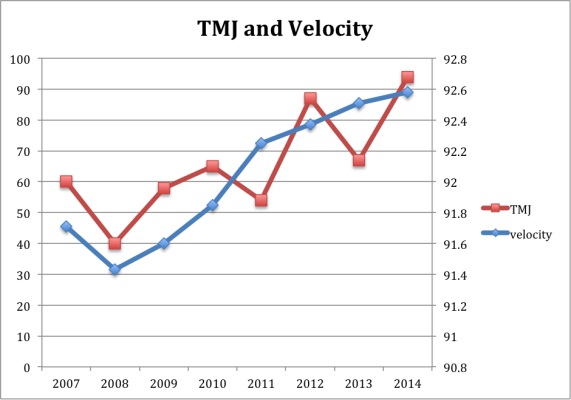

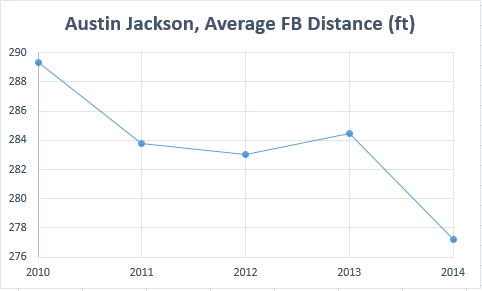

Mailhot astutely notes an alarming drop in well-hit groundball rate – from 64% above league average in 2012 to 11% below league average in 2014. This is accompanied by a commensurate rise in weakly-hit groundballs. Jackson’s well-hit line-drive rate also drops by a sizable amount, hovering around league average in 2014, while his rate of medium-hit line drives balloons to 198% of league average in 2014. Mailhot also points out possibly the most substantial shift: an immense drop-off in well-hit fly-ball rate in 2014 to 56% of league average, a trend corroborated by data pulled from Baseball Heat Maps on Jackson’s average fly ball distance over his career:

Jackson’s high rate of well-hit line drives and ground balls prior to 2014 puts into perspective the aspects of his game that brought him success earlier on in his career, and his sharp decline in those metrics in 2014 even more so. To put it in exceedingly simple terms, Austin Jackson just didn’t really hit balls hard in 2014, something he was quite good at doing before that season. Judging by the splits, most of the not-hitting-balls-hard occurred after the move to Seattle.

Jackson’s 2013 was much better than his 2014, but it is the beginning of a short trend of BABIP decline. From examining batted-ball data, we can infer that quality of contact has a significant bearing on BABIP, and this makes sense using conventional logic as well. Hard-hit line ground balls are more likely to find gaps between defenders, hard-hit line drives are more likely to drop in for hits, and hard-hit fly balls are more likely to turn into extra-base hits (although BABIP ignores home runs). The easy explanation is that Jackson lost some power in 2014. I don’t have enough film on Jackson to know for sure if there’s a visually concrete reason for this (if, for example, there’s something off in his swing mechanics), but data from 2014 indicates that Jackson just hasn’t been making good contact.

Jackson’s issues are probably best explained by his batted-ball troubles, but park factors likely play some part as well, with Comerica Park being relatively more hitter-friendly than Safeco Field. Safeco’s pitcher-friendly park factor and the ‘dead ball effect’ of Seattle’s marine air probably have something to do with Jackson’s decline in fly-ball distance, although Jackson is himself contributing to that same decline in some measure.

At the time of his acquisition, a merely average performance from Jackson would have been a significant upgrade over the convoluted mishmash that had previously taken the field for the Mariners. Unfortunately, he was unable to even provide replacement-value production after coming to Seattle, totaling -0.4 wins above replacement in 2014. The Mariners traded for an above-average player and received the production level of a player who theoretically wouldn’t cut it in the big leagues altogether.

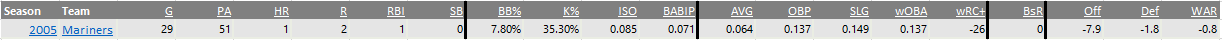

The prospect of 2015 being a bounceback year for Jackson has not gone over too well in these first few weeks. ZiPS (R) and Steamer (R) still think Jackson could manage 1.7-2.1 WAR on the season, which is a bit below his peak, but I think the Mariners would take that statline in a heartbeat. I’ve gone this far without mentioning Jackson’s other tools, but as a 28-year-old without a concerning injury history, there’s not as much reason to worry about his defense and baserunning as there is to worry about his offensive output. Jackson was a below-average defender by UZR in 2013/2014 and has been worth approximately 4 baserunning runs above replacement in each of the past couple of years, neither of which have dictated his value nearly as much as his offense, or lack thereof. Using those numbers as a serious predictive measure from year-to-year is simply not very useful at this point.

Lloyd McClendon was Jackson’s hitting coach back in Detroit, and suffice it to say he probably has a better grasp on Jackson’s habits as a batter than most. If anyone’s able to get Jackson back on track this season, it’s probably McClendon. At time of writing (the 18th of April), Jackson managed a slightly encouraging 2-hit, 1-walk performance against the Rangers. It’s early yet in the season, and there’s time for Jackson to hopefully figure things out. Alternatively, if Jackson can’t find some of his pre-2014 form this season, the Mariners might once again find themselves in the same trade deadline predicament from last year – only this time, there’s not an obvious trade chip à la Nick Franklin. Then again, 2015 is Jackson’s last year under team control, so the Mariners may simply choose to let him walk after the year is over if they’re not satisfied with his performance. If that’s the case, it’s hard to imagine looking back on the 2014 Jackson trade with anything but the same tinge of regret and frustration that has colored so many other Mariners transactions of the last decade.