The sabermetric revolution has brought us baseball nerds a lot of great information. More than anything, though, it has brought us a plethora of defensive statistics that help us understand a side of the ball that was previously mainly just measured by… (gulp) fielding percentage. Executives now pay top dollar for outfielders who take great routes to the ball, even if they make don’t have the strongest arm. Or an infielder who can get to a ton of balls, even though he makes more errors than the guy with no range.

Thinking about some of the top players in the league, they may not be as highly thought of as they are if we could not accurately quantify their defensive excellence. Francisco Lindor does not just look smooth at everything he does, but the numbers back him up. Conversely, Khris Davis at first glance looks like one of the best players in baseball, hitting countless long balls in Oakland. But Davis rates as one of the worst defensive outfielders in baseball and is not much more than a league-average player because of it. This led to me to thinking about, are the Davises of the world better than the Andrelton Simmonses of the world, who can field like Ozzie Smith, but hit like Mario Mendoza. I have created a list of nine players that are studs defensively but struggle hitting, and nine who work wonders with a bat but not with the glove. The teams will be compared at the end to see which one would come out on top if they were to actually play.

Defense

C – Salvador Perez – If you know anything about Salvy, as he is affectionately called, you know he is as durable as they come behind the plate. That, paired with his defense behind the plate makes him quite the valuable backstop. Salvador Perez has nine more Defensive Runs Saved since 2014 than the second place Yadier Molina, in a similar amount of innings. But offensively, Perez is not as strong. He has not had a wRC+ above 91 since 2013, excluding this year which is not halfway over. The guy just does not walk, as he has not had a BB% over four percent in any full season.

1B – Joe Mauer – Albeit a shell of his former self that used to strike fear into pitchers into the Metrodome, Mauer can still pick it at first. He is among the top at his position over the past few years at DRS, ErrR and UZR/150. Mauer does not have the power he used to, with isolated power hovering around .100 for the past few years. He walks a pretty solid amount, usually at around 10 percent.

2B – Yolmer Sanchez – A name not known to many, Yolmer Sanchez is a somewhat promising young player in Chi-town. Sanchez is not that experienced, but has shown positive defensive traits thus far. He is above average in turning double plays, not making errors and range. Despite that defensive success, Sanchez has not resembled any sort of an offensive threat. While improving this year, his OBP is usually well under .300, and his SLG% is also under .400.

3B – Darwin Barney – To have a 75 wRC+ and still finish with 2.4 WAR in a year says a lot about a player. That is was Barney accomplished in 2012. Talk about a journeyman utility guy; Barney has had some decent playing time in his career, notably with the Cubs, but for the most part, he has been an extra infielder with a slick glove at whatever position he is playing. At third, he has been solid in a limited amount of innings. He has a UZR/150 of 6 since 2014. Offensively though, he does not hit for power, does not walk and has been a below average baserunner the past few years.

SS – Jose Iglesias – The Tigers’ shortstop makes some of the smoothest plays in baseball. He is a treat to watch in the field, but no so at the plate. Iglesias has 12 career home runs, a walk rate under five percent and is a below average baserunner. He is in the top few among shortstops in defense as a whole, but is arguably the best at not committing errors.

LF – Colby Rasmus – When Rasmus is thought of by a normal fan, they probably think of towering home runs and excessive strikeouts. That is very understandable, but did a little deeper and you’ll find a very above-average defensive outfielder. Rasmus has the most Defensive Runs Saved of any left fielder, and he has fewer innings that almost anyone at the top of the leaderboard. Colby Rasmus has an insane arm in left, leading to an incredible UZR/150 of 30.3 over the past year and a half. Now he is by no means a bad hitter, but he is on the list because he is rather mediocre offensively, and stellar defensively. The only thing consistent about Rasmus is his astronomical strikeout rate. He is powerful, but has not gotten substantial playing time a lot because other parts of his game have been sub-par.

CF – Kevin Pillar – This is what Pillar is known for. He covers ground like few others can, while sacrificing his body for unbelievable diving grabs on a regular basis. Pillar’s RngR is the best in baseball over the past few years, and has saved nearly 40 runs since 2015. He is a well above-average baserunner, but his walk rate is under five, and his career OBP is right around .300.

RF – Jason Heyward – His $184-million contract with the Northsiders is also well worth it after that alleged speech he gave during the fateful rain delay in Game 7 of the World Series. But hey, it does not hurt that he is one of the best defenders in the game. Heyward’s UZR/150 since 2015 is over twice as high as the next qualifier. He has unbelievable range and a very good arm. Heyward has had offensive success in the past, but seems to have lost that magic with the Cubs. He has hit just 13 long balls since the start of 2016. The Cubs’ outfielder has his two lowest outputs of Hard% over the past two years.

Offense

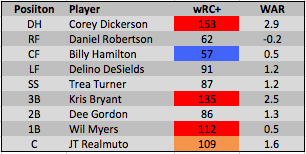

C – J.T. Realmuto – Realmuto has burst on the scene to an extent with his above-average offensive output in the past year and a half. In 2016 and in the start of 2017, his wOBA has been above .330, very solid for a catcher. He is also an above-average baserunner, and can even swipe you a few bags, as he did 12 times last season. Framing is not one of Realmuto’s strong suits, though. In his two seasons with the most playing time, 2015 and 2016, he combined for -27.2 Framing runs, per Baseball Prospectus. He has -10 DRS since 2016.

1B – Miguel Cabrera – The best right-handed hitter I have ever seen is not that great at defense. For context, Miggy’s RZR has been worse than Ryan Howard since the start of 2016. He is just jaw-dropping with a bat in his hands, though. The utter consistency of his sheer dominance of whatever is thrown at him is generational. He has had an OPS of .900 or higher in every year but two since 2005; three of the years, his OPS was well over 1.0. And in those two years he did not get there, he was very close, with an OPS in the very high .800s.

2B – Daniel Murphy – The spokesman of the launch-angle revolution has otherworldly numbers at the plate since the start of 2016. He batted .347 last year with just a .348 BABIP, implying his success was legitimate. His wOBA last year and this year thus far have been over .400. With all that though, he has been, without much question, the worst defensive second basemen in baseball since the start of last year. Murphy’s range what you would assume a player that looks to Pablo Sandoval to have. He also commits more errors than average.

3B – Jake Lamb – One of the biggest reasons the Diamondbacks are having the season they are is because of their third baseman. Lamb is walking a lot and hitting with a lot of power, a recipe for success. He is not that great at the hot corner though, as he has been below average at making errors and turning double plays while managing to have limited range.

SS – Xander Bogaerts – The Aruba native has not replicated the success he had for most of last year during this year, but is still clearly an above-average offensive shortstop. He has had an OBP of over .350 for three straight years now and has cut his SwStr% down severely, all the while being an incredible baserunner. The questions about his glove, though, have turned out to be legitimate. He makes very few plays out of his zone because of his lack of range.

LF – Matt Kemp – Remember when Matt Kemp was arguably the best player in baseball? He is a far cry from that, plus a few pounds. He is still hitting well over .300 with power. His Soft% is very low, as it has been for years. According to FanGraphs, he has a lifetime defensive WAR of -143.3. There are a lot of bad defensive left fielders in baseball currently, notably Robbie Grossman, Yasmany Tomas and anyone in Baltimore, but Kemp may be the worst.

CF – Tyler Naquin – Oh boy. I saw Naquin’s downfall coming before it happened, but he was still overall a productive player offensively last year, if you look at the season as a whole. His wRC+ was 135, albeit clearly unsustainable. Naquin’s BABIP was .411, and he really struggled in the second half. He was a disaster in center field, taking some of the worse routes I have ever seen. He did have a pretty solid arm, but he used it too much because of how many extra-base hits he allowed.

RF – J.D. Martinez – This is what bursting on the scene actually looks like. Martinez has put up jaw-dropping numbers over the past few years, relative to what he had in years past. Martinez’s OPS has been .879 or higher every year since 2013, including in 2017, where he is currently at 1.065. Statistically though, Martinez does not really do anything well in right field. He has been way worse than Jose Bautista since 2016 in fewer innings.

To me, the most evident difference between these two hypothetical squads is the name recognition. Nearly every player on the offensive-heavy team is a household name, or has some form a popularity. The other team, though, has one, arguably two names that the average fan would know. Name power, though, does not translate to wins. These two teams playing would make for some interesting baseball. The defensive squad would be a treat to watch play together, but it would be tough for them to field the rockets hit at them by Miggy and co. I decided to calculate how the WARs of these players stack up. I calculated the average of their WAR last year (expanded to 150 games) and their WAR this year (again, expanded to 150 games) of those that are playing.

|

Defensive Team |

Offensive Team |

| C |

Salvador Perez – 3.9 |

J.T. Realmuto – 3.9 |

| 1B |

Joe Mauer – 1.2 |

Miguel Cabrera – 3.1 |

| 2B |

Yolmer Sanchez – .9 |

Daniel Murphy – 5.4 |

| 3B |

Darwin Barney – 1.3 |

Jake Lamb – 3.6 |

| SS |

Jose Iglesias – 2 |

Xander Bogaerts – 5.2 |

| LF |

Colby Rasmus – 3.4 |

Matt Kemp – 1.6 |

| CF |

Kevin Pillar – 2.1 |

Tyler Naquin – 3.2 |

| RF |

Jason Heyward – 1.9 |

J.D. Martinez – 3.8 |

| Total |

16.7 |

29.8 |

Now what does this tell us? Not a whole lot. Not only is WAR not a perfect stat, but a lot of these are skewed, like Tyler Naquin. I would project Naquin to almost have a negative WAR in 2017, but because he had a lucky 2016, and has not really played in 2017, he has a 3.2 WAR. Conversely, there is someone like Kevin Pillar who is off to not a great start in 2017, but should turn it around, and is punished because his WAR is not that high yet.

I would project the offensive team to win, though. Again, that does not tell us a much. I just picked players who I saw as bad at one part of the game and good at another. Someone else doing this could have picked other players and gotten a much closer result. This defensive team I chose would have a very hard time scoring runs, and while the offensive squad may struggle in the field, notably with range, they have so much firepower that they could be not be slowed down. I would love to see these teams battle, as it would make for some long home runs and exciting plays in the field, but I think these guys are doing just fine on their own teams.

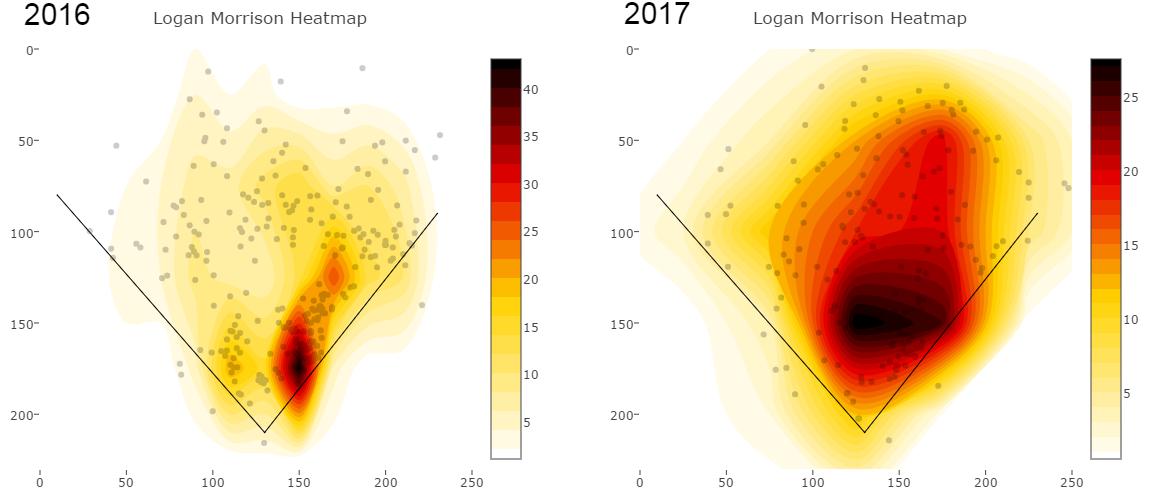

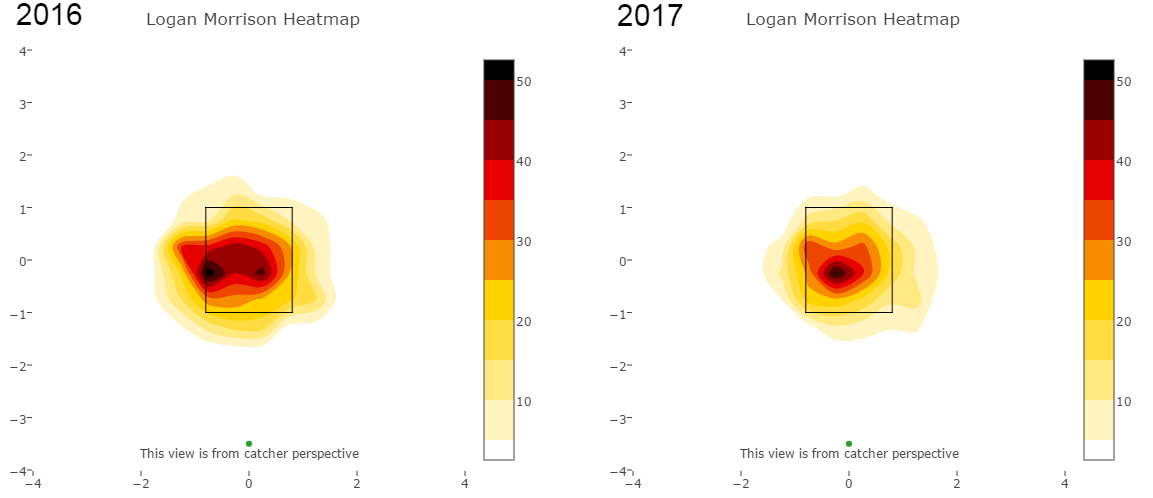

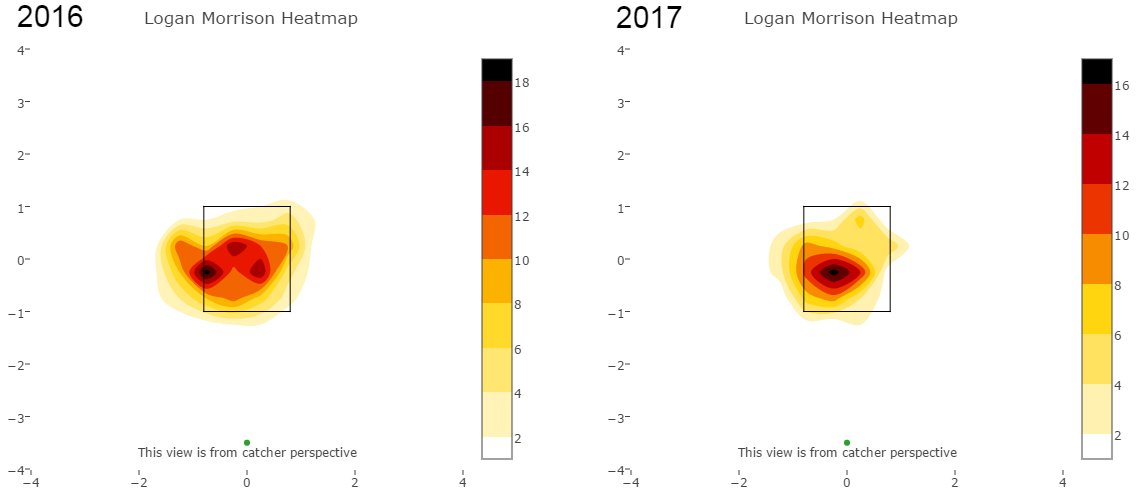

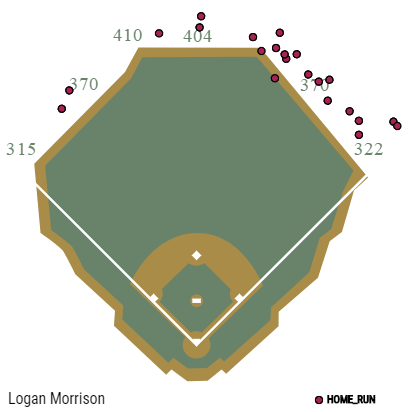

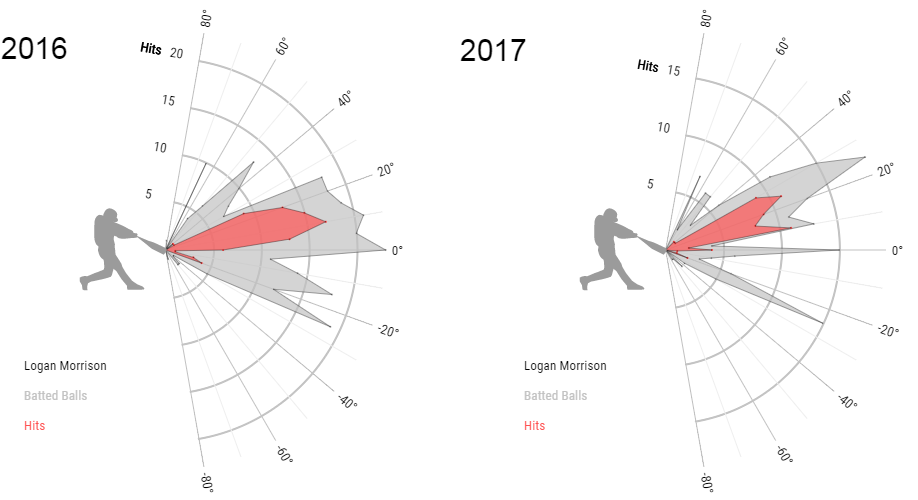

Further, look at how much his spray chart has shifted towards the middle of the field:

Further, look at how much his spray chart has shifted towards the middle of the field: