The Correlation Between BABIP Rate and Three True Outcomes

First things first, I would like to credit my friend Elling Hofland for coming up with the main idea of this piece. He’s the one who provided me with his thoughts and theories that allowed me to expand on this topic in the first place. Give him a follow on Twitter for sports and stats-related banter; his handle is @ellinghofland.

BABIP, or batting average on balls in play, is an incredibly useful stat. It does a fantastic job at using both luck and quality of contact to give a better grasp as to how a player actually performs during batted-ball events. These batted-ball events only take up a certain percentage of a player’s plate appearances. BABIP rate focuses on how many plate appearances a player has relative to the number of batted-ball events they have. To calculate BABIP rate, you take at bats minus strikeouts and home runs, plus sacrifice flies, and divide that by plate appearances. For example, if a player has 600 PA during a single season along with a 300 batted-ball events, they have a BABIP rate of .500.

Now, if you look at the three variables taken out of that equation, you’re left with walks, strikeouts, and home runs, otherwise known as the “three true outcomes.” These are called true outcomes due to the fact that none of them (for the most part) involve defense on the field. A shortstop can’t screw up a strikeout, walk, or a home run. You can take these three true outcomes and turn them into a rate as well. If you add up a player’s strikeouts, walks, and home runs and then divide them by plate appearances, you get TTO rate.

Let’s look at Mike Trout. In 2017, Trout’s BABIP currently sits at .369. However, he has a BABIP rate of .550 along with a TTO rate of .435, meaning that 55% of his at bats end with a ball in play, while 43.5% of his plate appearances result in a strikeout, walk, or home run. Both BABIP rate and TTO rate are useful stats, as they essentially show how well and how often a player makes contact. While BABIP itself is useful, it can be hard to tell how luck is involved in a batted-ball event when it isn’t hit over a fence for a homer. BABIP rate attempts to bridge the gap between BABIP and the three true outcomes.

Miguel Sano is a well-known slugger. In his three seasons in the majors, he’s smashed the ball when he’s hit it, boasting exit velocities of 94.0 in 2015, 92.3 in 2016, and 93.1 in 2017. Despite these consistent EVs, his BABIP has fluctuated from 2015 to 2017, with marks of .396, .329, and .385, respectively. If we look at his BABIP rate from 2015-2017, they look like this: .429, .478, and .473. Despite the difference in his BABIP from 2016 to 2017, his BABIP rate has stayed nearly the same, meaning that he’s still making the same amount of contact with the ball despite fewer balls falling for hit in 2016. Looking solely at BABIP, it could be argued that 2016 was his “regression” to where he should be after sporting an incredibly high BABIP in 2015. In 2017, one could say his high BABIP is a cause for concern, as he may just be getting lucky. However, his BABIP rate shows that isn’t the case.

Let’s look at another player, Brandon Phillips. Phillips’ BABIP has been incredibly consistent during his past three years, sitting at .315 in 2015, .312 in 2016, and .305 in 2017. Additionally, his BABIP rates have been .820, .816 and .802. Phillips puts the ball in play nearly 80% of the time on a regular basis.

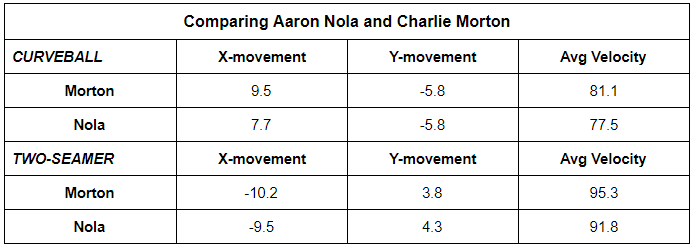

So, as you can imagine, there is a real link between BABIP rate and TTO rate. The more contact a player makes, less they tend to walk or strikeout. Thus, a high BABIP rate equals a low TTO rate. This is exactly what we see if we attempt to correlate these two stats. Below is a snapshot of a graph that shows TTO rate vs. BABIP rate.

Players names aren’t included because, A) it clutters the graph, and B) they aren’t necessary at this point. Accompanying this graph is a trend line with an R squared value, otherwise known as a correlation coefficient. Essentially, an R squared value measures how well your model fits your data, or in this case, how closely correlated TTO and BABIP rate are to each other. It turns out that the R-squared value is .991, which means that the relationship between BABIP rate and TTO rate fit very well together: in fact, you’ll find that TTO rate and BABIP rate are almost the exact opposites of each other. The players with the top 10 lowest BABIP rates in the MLB all have TTO rates of .437 or higher, meaning that their at bats result in an outcome of a walk, home run or strikeout 43.7% of the time. Inversely, players with the lowest BABIP rates all have TTO rates of .225 or lower.

We can also derive more information from these numbers using this correlation. Players who have a low BABIP rate have a very high OPS. Remember, these players also have high TTO rates. The top 10 players, Judge, Sano, K. Davis, Souza Jr., Reynolds, Morrison, J. Upton, C. Santana, Lamb, and Stanton all have an OPS of .841 or higher. The players with the highest BABIP rates (or lowest TTO rates) have an OPS of .798 or lower.

BABIP rate can tell us a lot of about a player. Just by glancing at a player’s BABIP rate, you can have an instant idea of how often the player walks, strikes out, or hits dingers. Not only that, but it you can tell you a lot about their offensive production. High TTO rates usually mean high hard-hit rates along with high exit velocities. BABIP rate also helps understand BABIP itself better and teaches that you can’t judge a player by BABIP all the time. In most cases, players with an over-inflated BABIP (relative to past performances), just tend to mash the absolute heck out of the ball, as told by their low BABIP rates and high TTO rates. On the opposite end, players with a steady BABIP will have very high BABIP rates and tend to be contact hitters that put the ball in play and don’t hit for power. BABIP rate, along with its correlation to TTO rate, has the potential to be a powerful, tell all offensive stat.