Every season, pitchers and pitching coaches across the league tinker with pitch arsenals, with varying effectiveness. This series examines the pitchers who have most significantly changed their arsenals in 2018, beginning with starting pitchers who have added new pitches.

This season, a handful of big-name pitchers have added a new weapon to their arsenal, including Nationals ace Max Scherzer. Below, we’ll look at Scherzer and his pitch adding companions in detail, in order of their new pitch.

Cutters

Max Scherzer, Nationals (Statistics through July 29th)

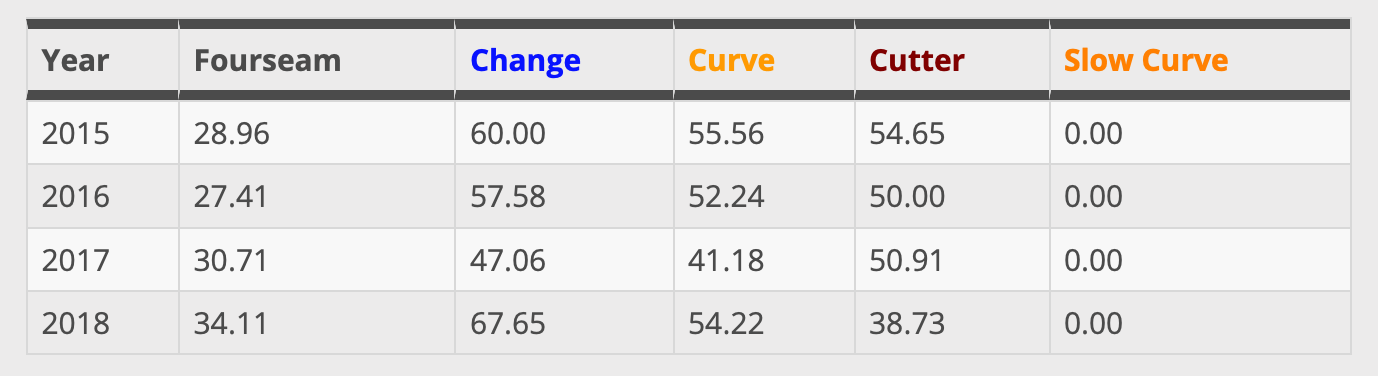

Even in the midst of a relatively down season for the Nationals, Mad Max has put together another terrific season, currently sitting at a 2.30 ERA and 4.8 fWAR. Already a three-time Cy Young Award winner, the ace righty has added a new weapon to his pitch mix this season. Scherzer has added a cutter, a pitch he toyed with in 2015, to his arsenal, and used it fairly regularly this season after not employing it at all last season. Scherzer’s pitch mix for the last two seasons is displayed in the following table:

As the table shows, Scherzer’s fastball, curveball, and changeup usage have remained about the same (as have the velocities on each pitch) while he’s shifted his focus away from his slider and towards his cutter. The new pitch is averaging 88.4 mph, a few ticks faster than the slider. Scherzer’s located both pitches similarly, throwing both pitches primarily low and on the left-hand batter’s box side of the plate. The cutter (pitch usage chart below on the left) has been used more inside to lefties, while the slider (right) has been kept low and away to righties.

However, there is one key difference between Scherzer’s cutter and slider usage: of the 242 cutters he’s thrown, only 7 have been to righty hitters, while only 3 of the 375 sliders he’s thrown have been to lefties. The development of his cutter has allowed Scherzer to avoid using his slider against lefties (who have slugged .368 off it career, compared to .270 vs righties) while keeping a four-pitch mix in play. While the pitch has only been about league average this season (with a weighted pitch value of 0.11 wCT/c), it may provide him a better weapon against lefties than his slider has. To this point, lefties have actually slugged .450 off the cutter this year (in a small sample), although they’re only hitting .183 against the pitch, and his overall line vs LHH is much improved this season (.189/.252/.349 with a .260 wOBA compared to .213/.299/.392 with a .299 wOBA in 2017). Only time will tell, but Scherzer’s been even better this season, and it may be in part due to his new pitch.

Carlos Martinez, Cardinals (Statistics through July 29th)

Another NL fringe contending team’s ace, another new cutter. Martinez began tinkering with a cutter this spring and has carried it over into the regular season. The hard-throwing righty has turned the cutter into a significant part of his arsenal, ranking 26th out of the 148 starting pitchers to throw at least 50 innings this season in cutter usage. Martinez has shown one of the most drastic changes in pitch mix of any starter over the past two seasons, with the cutter being the largest catalyst for this change.

As you can see in the table above, Martinez’s new pitch has largely come at the expense of his fastball, which has dropped in usage by 12%, marking the 3rd largest decrease in fastball usage between 2017 and 2018 of any starter in the sample. The Dominican righty has also leaned less on his slider since developing the cutter, which sits between 90-91 mph, about three ticks below his usual fastball and seven up from his slider. Martinez utilizes both a sinker and a four-seam fastball in addition to the cutter and uses each fastball in a different part of the plate. As illustrated in the pitch usage charts below, he tends to stick low and away (to a righty hitter) with the cutter (left plot), locates the sinker mostly down and inside (middle plot), and lives up in the zone with his four-seamer (right).

Martinez’s newfound cutter (an above average pitch with a wCT/c of 0.73) has also given him a nice complement to his slider, which he primarily uses low and away to righties and down and into lefties, but as mentioned sits at a much lower velocity than the cutter. It is worth noting that Martinez has rarely used the cutter against righties but has, in fact, used it as his go-to pitch versus lefty hitters, according to Brooks Baseball. Thus far, CarMart’s cutter has been an effective weapon against southpaw swingers, who are batting only .220 with a measly .305 slugging percentage on the offering. Additionally, Martinez has done a much better job overall of handling lefties on the season, holding them to a .228/.350/.332 slash (good for a .307 wOBA) after allowing a .260/.342/.441 slash (.337 wOBA) to opposite-handed opponents last season. Although Martinez has taken a step back against righties this season (allowing a .301 wOBA in 2018 compared to .263 last year), it seems that Martinez has an effective new weapon in his arsenal.

Sonny Gray, Yankees (Statistics through July 29th)

While both other pitchers discussed so far have had success this season, Gray has struggled to a 5.08 ERA on the campaign and has slipped down the depth chart in a Yankees rotation he was brought in to stabilize at the deadline last year. It’s worth noting that Gray is the most recently moved of the pitchers discussed, and his deal to the Yankees may well play into his changing pitch mix. Since the start of last season, the Yankees rank last in the major leagues in fastball usage, with just 39.3% of deliveries recorded as fastballs. Following this trend, Gray has seen a drastic shift away from using his fastball since donning the pinstripes, with his FB% dropping more than any other pitcher from last season. A comparison table of Gray’s pitch mix the past two seasons illustrates the change in pitch mix for the former Vanderbilt Commodore:

There’s a lot to unpack here, obviously starting with the cutter usage. Gray’s cutter usage ranks 17th in baseball among starters with 50+ IP this season, after not being utilized in 2017. As discussed earlier, the FB% is way down, as is the changeup usage, giving way to an increase in curveball frequency. Gray’s slider usage remains largely unchanged, holding steady in the mid-to-upper teens. In 2017, all of his pitches graded positively, with the slider standing out the most (1.06 wSL/c), but this season has been an entirely different story, with every pitch besides the curve (0.94 wCB/c) grading as below average and the cutter grading especially poorly at -1.77 wCT/c (to say nothing of the changeup, which has graded poorly but not terribly in the past, clocking in at -6.60 wCH/c, although small sample size should be noted here). There’s been plenty written about Gray’s struggles already this season, but it’s probably worth noting that his shift toward the cutter may not be helping him.

Slider

Jameson Taillon, Pirates (Statistics through August 3rd)

After missing a portion of the 2017 season to battle cancer, the Pirates righty is in the midst of a very solid season, running a 3.58 FIP/2.1 WAR through his first 22 starts. Some of this success may in part be chalked up to Taillon’s new slider, which he debuted in earnest during his May 27 start (written up here by Rotographs’ Paul Sporer) against Martinez’s St. Louis Cardinals after dabbling with it in a few earlier starts. Taillon has since made the slider a significant portion of his arsenal, utilizing it 13.5% of the time thus far in 2018. His pitch mix across the past two seasons is displayed below:

As Taillon has added a slider to his repertoire, its usage has come primarily at the expense of his curveball and sinker, which has seen the most dramatic drop in usage. Despite this decline, Taillon is still carrying a solid 49.2% groundball rate (up slightly from last year’s 47.3%). This may be in part due to the fact that Taillon’s new slider has generated a high rate of grounders (generating a GB% of 52.38%, per Brooks Baseball). The new pitch stands out in another way as well: thus far in 2018, Taillon’s slider ranks third in the majors (among qualified pitchers) in slider velocity at 89.9 mph. Taillon has thrown 174 sliders against right-handed hitters this season and has primarily located low and away, while most of the big righty’s sliders against opposite-handed hitters have been down and in, as shown in the zone profiles below (vs left on the left, vs right on the right):

Although it’s impossible to discern exactly how much of an impact the pitch has had on Taillon’s improvement this year, it is worth noting that the pitch ranks 18th among qualified pitchers in Fangraphs’ Pitch Value among sliders at 1.40 wSL/c. Although right handed hitters have had success against the pitch thus far (.263 BAA with a .491 SLG), the new pitch has devastated lefties this season, who are hitting a measly .160 with a .240 slugging percentage off the pitch. Taillon’s overall line against lefties is also much improved compared to last season (.321 wOBA this season vs. .355 in 2017), although it’s worth noting that Taillon’s numbers from last season are likely distorted by a rough second half following his return from cancer treatment. He’s also been more effective vs. righties and seen improvements in pitch value on both his fastball and curveball as well, possibly due in part to the new threat of his slider. After displaying strong talent and remarkable perseverance last season, Jameson Taillon has added a new weapon to an already strong arsenal en route to a very strong 2018 season.

Curveball

Patrick Corbin, Diamondbacks (Statistics through August 4th)

Coming off a solid but unspectacular 2017 season (4.08 FIP), Patrick Corbin seems to have taken a major step forward in his walk year, compiling 4.3 wins above replacement on the back of a 2.56 FIP through 141.1 innings pitched this season. The lefty has seen his strikeout rate jump more than nine percent from last season (21.6% in 2017, 30.7% in 2018), and has done so with a new weapon in his arsenal: a curveball he seems to have debuted in his April 17th start against the division rival Giants. Corbin has used the pitch a little over a tenth of the time (10.6% of his deliveries to be exact) and has seen it become his third option in a pitch mix that heavily features sliders and fastballs. Here is Corbin’s pitch mix over the past two seasons:

Corbin’s fastball (averaging 90.5 mph this season) and slider (81.6 mph) usage have remained largely the same, as the addition of Corbin’s curve has come largely at the expense of his changeup, which the lefty rarely uses. The new curve has averaged 73 mph on the season, coming in about nine ticks slower than Corbin’s primary breaking ball. Per Brooks Baseball, Corbin’s curveball seems to be of the 12-6 variety and has been used almost exclusively against opposite handed hitters, who have seen 218 of the 219 deliveries registered as curveballs by Brooks. Additionally, it is worth noting that over half of the curves Corbin has thrown have been to start an at bat, and that the pitch has resulted in the highest percentage of strikes of any pitch Corbin throws (although the slider isn’t far behind). Corbin has located most of his curves down and away to righties, further contrasting to the slider (below right), which the soon-to-be free agent has buried down and in against righty opponents.

Although opponents have batted .294 and slugged .471 against the pitch in a small sample this season, it appears to be a more effective weapon against righties than the now-infrequently-used changeup, against which righty opponents have batted .339 and slugged .617 over the course of Corbin’s career. Corbin has also subdued righties much more effective overall this season than in the past, having held them to a .245 wOBA in 2018 compared to a career (including 2018) .324 line. It certainly seems plausible that Corbin’s shift away from changeups to opposite-handed hitters and towards early count curveballs (161 of the 218 curves to righty batters have come in 0-0, 1-0, or 0-1 counts) has helped him to more effectively dispatch opposite-handed opponents than ever before. Fangraphs’ Pitch Values also seem to offer support for his idea, grading Corbin’s curve as a positive pitch (0.38 wCB/C), whereas the changeup has graded as negative in every one of Corbin’s six seasons (with a net value of -2.27 wCH/C). Additionally, both Corbin’s slider and fastball have played up this year to the tune of career-best pitch values, possibly due to the threat of a third positive pitch against righty hitters. This has allowed Corbin to become a more well-rounded pitcher during an excellent season and helped pave the way to a potentially lucrative offseason deal.

Data courtesy of Fangraphs and Brooks Baseball. Zone profiles all from catcher’s perspective, courtesy of Brooks Baseball. In instances where pitch type disagreements existed, Fangraphs pitch data was prioritized over Brooks Baseball. Pitch Mix tables based on Fangraphs data.