It’s no secret that the American League has been incredibly top heavy this year, with the playoff race having essentially been decided by the All-Star break (insert crying emoji for Angels’ fans). The Astros, Yankees, and Red Sox have been incredible, ranking first, second, and third respectively in total team WAR. The Mariners have been a pleasant surprise, parlaying a breakout season from Mitch Haniger and dominant pitching from Edwin Diaz and James Paxton with a ludicrous record in one run games (that almost certainly won’t be sustained over the course of a full season). Lurking just outside of the playoff picture are the exciting, young Oakland A’s, who have an interesting mix of young blossoming stars and seasoned vets, all who seem to be clicking at the right time.

Forgotten in all of the competitiveness that defines the AL West and AL East is the mediocrity of the AL Central. Much has been written about how historically bad the division is this year, which houses three rebuilding teams—the Tigers, White Sox, and Royals—and a vastly underperforming/fringy pre-season playoff contender in the Twins. As it currently stands, those four teams all project to finish below .500, with the White Sox and Royals both on pace to lose over 100 games. There is one bright spot, though; this team won 102 games in 2017, lost in extra innings of game 7 of the World Series in 2016, and is home to a two-time Cy Young award winner and the best SS/3B combo in the MLB. That team is the Cleveland Indians.

(Note: All statistics are current as of 07/02/18)

The Tribe have flown under the radar this year in terms of AL World Series contenders, partly because the Astros/Yankee/Red Sox have been so great, and partly because the Indians… well, haven’t been. Early on in the season, the lineup struggled mightily to score runs, couldn’t get reliable starts out of their 5th rotation spot (re: Josh Tomlin), and had a revolving door in the bullpen. As many expected, the offense snapped out of its funk, and now rank 6th in the MLB in total team batter WAR with 14.8, thanks to monster first halves from Francisco Lindor (.936 OPS, 153 wRC+, 21 HRs), and Jose Ramirez (1.007 OPS, 169 wRC+, 24 HRs). The rotation is now as formidable as ever, ranking 2nd in total SP WAR with 11.0, and replacing Tomlin with a combination of a serviceable Adam Plutko and top prospect Shane Bieber. Not to mention, Trevor Bauer and Mike Clevinger have taken massive steps forward, Corey Kluber has maintained his ace status, and 2017 4th place Cy Young finisher Carlos Carrasco hasn’t even found his stride yet. The team is positioned as well as anyone to make a deep postseason run… if their bullpen wasn’t still an atrocity. Take a look at this chart from Sunday’s game against Oakland.

View post on imgur.com

Going down the list, everything looks pretty good until… WOW. A bullpen ERA over 5, up almost 2.5 runs from a season ago. The bullpen might not be quite as bad as they appear on the surface, as they are running an abnormally low LOB%, as well as an unsually high HR/FB rate—which explains why their xFIP is 4.11 compared to their 5.17 ERA/4.64 FIP. The Tribe’s relief corp ranks nearly dead last in total team RP WAR, and their futility—combined with the excellence of the starting pitching—has led Terry Francona to only use his pen for 222.2 innings this year, good for dead last in the MLB. From 2016-2017, the Indians had the 4th best bullpen in baseball by WAR, including the best bullpen ERA and FIP, and the second best xFIP. What happened to this once formidable group? For one, the team lost bullpen stalwart Bryan Shaw via free agency, as well as mid-season acquisiton, Joe Smith. From 2013-2017, no relief pitcher threw more innings than Shaw, who carried a solid 3.11 ERA over those 5 seasons. In addition, superstar Andrew Miller has thrown just 14.1 innings, having been on the shelf for 52 days this season across two separate DL stints. Because of this, Francona has had to rely on closer Cody Allen much more than he would like to, with the results being slighly underwhelming. Allen’s ERA has jumped from 2.94 in 2017, to 3.62 in 2018, all while running an abnormally low BABIP of .233. This seems to suggest that there’s more regression on the way, which doesn’t bode well for a guy who’s K% has fallen almost three percent, and who’s out of zone swing rate has decreased while his out of zone contact rate (and overall contact rate) have increased.

Take a look at the motley crew the Tribe has run out this year (no bullpen carts yet in Cleveland, unfortunately).

View post on imgur.com

When two of the top three guys in innings pitched have combined for -0.5 WAR, you know things aren’t good. Oliver Perez and Neil Ramirez have actually been pretty solid over the last month or so, but those aren’t the guys you want coming in to face Aaron Judge, JD Martinez, or Carlos Correa in October. With both Cody Allen and Andrew Miller likely to be in different uniforms next season, it would greatly benefit the Tribe to capitalize on the team they have now by fortifying their biggest weak spot with pitchers controllable past this season alone. MLB Trade Rumors confirmed this idea, writing, “The Indians hope to acquire at least one quality reliever who’s under control past this season, per [Buster] Olney.”

So, who fits that mold? Obviously, we can rule out a few teams right off the bat:

- Astros, Red Sox, Yankees, Mariners, Nationals, Braves, Phillies, Cubs, Cardinals, Brewers, Dodgers, Giants, Diamondbacks, Rockies, A’s, Twins, Tigers, Royals, White Sox

All of those teams in that list are firmly entrenched in playoff races, or have invested enough in their team that it would be tough to justify tearing it down right now. The A’s are interesting, given their penchant for selling off productive players at peak value. I think their recent success and competitive timeline will lead them to hold onto their stud closer Blake Trienen, though. I also added the other AL Central teams in there, given that it is unlikely they would like to trade within the division (which for the record, is stupid).

That leaves the following teams as potential trade partners:

- Rays, Blue Jays, Rangers, Angels, Orioles, Padres, Pirates, Reds, Marlins, Mets

I find it highly unlikely that the Rays move another controllable bullpen piece, given their recent success with the “opener” and the fact that they already traded their former All-Star closer, Alex Colome. The Angels came into the year expecting to compete for a playoff spot, but injuries have derailed them this year. They will be looking to bounce back next year, and probably will only sell off short-term assets. The Mets don’t have anyone worth trading for, while teams like the Pirates and Blue Jays with ace closers (Vazquez and Osuna, respectively) probably will cost too much in prospect currency. The Orioles have relief pitchers with solid track records, but Britton/Brach are both free agents at the end of the year, and Darren O’Day is out for the year after hamstring surgery. Mychal Givens—who is a good reliever in his own right—is controlled through 2021, but probably isn’t the type of arm you can count on as the main guy in a bullpen.

That leaves four teams to choose from: Rangers, Marlins, Reds, and Padres. While each of the first three organizations possess quality, controllable arms, I think the Indians should be aggressive in obtaining Padres’ relievers Brad Hand (LHP) and Kirby Yates (RHP).

While Hand has been an above average reliever for a few years now, Yates really has broken onto the scene this year. Check out some numbers and rankings and see for yourself:

View post on imgur.com

Both rank in the upper echelon in K%-BB%, which shows an ability to miss bats while still maintaining command of the zone. Hand’s ERA and FIP look better, mostly because he had more success in previous years than Yates—although this season Yates is actually vastly outperforming Hand in this area. For those that don’t know what SwStr% means, it is calculated by dividing swings and misses by total pitches thrown by the pitcher, with league average being around 9.5%. Both Hand and Yates are well above average in this category, with Yates’ numbers bordering on elite. These two excellent relievers would fit in nicely in 2018 with a healthy Andrew Miller and a less overworked Cody Allen, and also would provide a sturdy base for the 2019 relief corps that are almost certainly going to lose the two aforementioned Indians.

Check out these two surplus value graphs that I calculated for both Padres relievers:

View post on imgur.com

View post on imgur.com

Let me briefly explain my methodology. When calculating surplus value on a contract, the goal is to figure out how much “extra” value the player is giving to his team by subtracting the market value for his production by the dollars he is actually owed via his contract. The $/WAR calculation for 2018-2020 were taken directly from an article written here on Fangraphs by Matt Swartz, and the expected WAR totals were generated by the generally accepted decline rates laid out by former Fangraphs’ editor and chief, Dave Cameron. Players on average perform at 90% of their previous year’s WAR output through age 30, 85% from 31-35, and 80% from 36 and up. For 2018 dollars owed, I divided each players’ contract by 3 to account for the fact that each would only be in Cleveland for about a third of the current season. Similarly, the 2018 final WAR calculation shown at the bottom of my charts uses 2016 and 2017 WAR totals added to each player’s current WAR, plus an average of what Zips and Steamer—which are Fangraph’s projection systems—think they will produce the rest of the season. Finally, that total is then divided by three to get the average of the three seasons, and then divided by three again, to account for the third of the season Hand and Yates would pitch for the Tribe. Using the previous two seasons WAR in addition to the current season will enable us to have a number that is less influenced by one particular season’s performance, thus giving us a sturdier baseline for which to calculate the next season’s WAR totals.

These charts aren’t perfect, and are meant to be used as simply a rough estimate to see how valuable each player would be over the course of their contracts. For example, Yates will head to arbitration in 2019 and 2020. It is tough to say how much of a raise he will get each season, so I kept the raises equal, and simply doubled his previous year’s salary. Arbitration pays for saves, as well as other counting statistics like strikeouts and holds. Since Yates probably will never do much closing, and really hasn’t become dominant until this season, I feel comfortable saying his salary won’t escalate too much the next few years—which is great for a small market team like the Indians.

Clearly, if we can ascertain how valuable Hand and Yates are, the Padres certainly know their value as well. What would it take to get both of these guys? Would it take a massive overpay? Is there a point where it becomes too expensive? The answer, in short, is “it depends.” The Padres have an absolutely loaded farm system, so they might have more specific desires when it comes to prospect returns. Of course, prized Tribe prospect Francisco Mejia’s name will most definitely be talked about first. I’ve seen him ranked anywhere from a 55FV to a 60FV on the 20-80 scouting scale, meaning some see him as an above average MLB contributor, while others see him as a potential All-Star. Using Kevin Creagh and Steve DiMiceli’s prospect valuation model, which according to Dave Cameron “looks at the level of expected performance and the expected cost of a player during the years before he reaches free agency, and then estimates a player’s value to his organization during that time,” here is how top prospects can be valued:

View post on imgur.com

As you can see, pitchers are valued less due to the fact that pitcher’s get injured much more than hitters, and thus are riskier over the course of their control years. Depending on how you value Mejia, there’s a 22-million-dollar difference in his estimated prospect value. To elaborate, if Hand/Yates combined are around 40 million dollars in surplus value by my model, Mejia’s value outweighs theirs by 20 million if he is a 60FV, while it actually is about 2 million less if he ends up a 55FV. Is there a lot more that goes into trades than simply surplus value? Absolutely. Teams all have their own ways of valuing MLB/MiLB players, and the value of a championship sometimes is the necessary boost to make a move that might be otherwise unadvisable (see: 2015 Kansas City Royals).

Based on what I’ve seen/read, it’s tough for me to value Mejia at a 60FV, mostly due to the uncertainty surrounding his long-term projectability behind the dish. Everyone knows he has an absolute hose, but it appears as if his footwork, blocking, and game-calling need work. Not to mention, he doesn’t have a traditional “sturdy” catcher’s frame, and there is legitimate concern that his body will not hold up after catching 110+ games a season. If he isn’t able to develop into an average to slightly above average catcher, it’s not as if his advanced barrel control from both sides combined with some sneaky raw power won’t play at a corner outfield spot or 3B. That profile will just will make him less valuable, because it is extremely difficult to find a catcher that can hit as well as Mejia is projected to.

Let’s construct two trade scenarios based on Mejia being a 55FV prospect. Because of the scarcity of dominant relievers on the trade market with team friendly contracts, and the fact that the demand for Hand/Yates will be high among contenders, the Tribe will probably have to overpay for their services.

Here’s two mock trades I think could work:

View post on imgur.com

View post on imgur.com

We’ve already talked in length about Mejia, but here’s some quick information on the other guys I included in this deal (note: all FV ratings are via Fangraphs). Talking about deal number one first, Willi Castro (45FV) is a slick fielding SS with solid contact ability, and would fill in nicely at SS if top Padres’ prospect, Fernando Tatis Jr., moves off of short like many are expecting. Quentin Holmes (40FV) is a plus runner with immense athleticism that will help him play plus defense in CF someday. The hit tool isn’t there yet, but if he develops the way the Tribe are hoping, he will be a key cog at the top of a lineup down the road. Julian Merryweather (NR) is a big, right-handed reliever that Fangraph’s prospect analysts Eric Longenhagen and Kiley McDaniel have up to 98MPH, with a plus curveball and changeup. He’s coming off Tommy John surgery, but is an interesting high-upside bullpen piece that could break camp with the team as early as 2019. In the second deal—not including aforementioned Mejia and Merryweather—there is Yu Chang (50FV), who probably has just enough athleticism/twitchiness to stick at short, but also could fill in nicely at 3B down the road. He has some swing and miss issues, but there’s legitimate raw pop in his bat, and he should be able to get to that power in game enough to be a valuable everyday regular. Jordan Milbrath (NR) is a massive 6’6” 215lb reliever that has what Longenhagen and McDaniel describe as a plus sinker and slider.

Will either of these deals be satisfactory to the Padres? Who knows. Will the Indians think that Mejia headlining a deal is too expensive? Who knows. These mock trades were meant to put out a framework of what could potentially move the needle on two relievers with justifiably high price tags, all while staying within the parameters of what a fair deal would be in terms of surplus value.

With the recent departure of LeBron James, and the consistent futility of the Browns (save us, Baker Mayfield) the Indians are Cleveland’s best chance at fielding a championship team over the next five years. Although the price might be steep, it’s impossible to put a dollar amount on what a World Series would mean for the city of Cleveland, even if it requires trading an arm and a leg for a Hand (and a Yates).

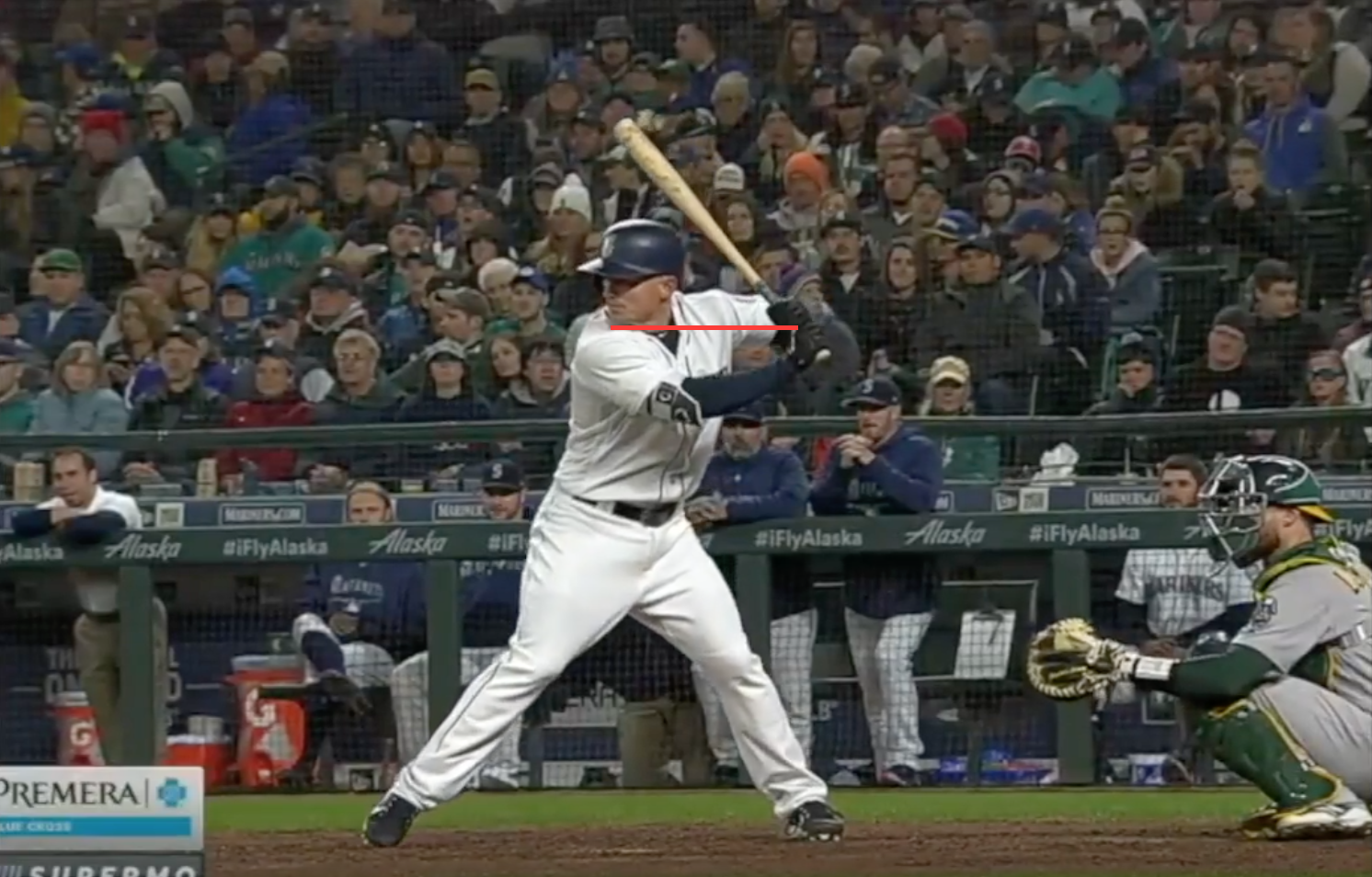

Seager’s hands appear much closer to their 2016 position. His average launch angle on line drives and fly balls combined is eerily similar to last year at 29.6° but his line drive launch angle has gone down while his fly ball launch angle has gone up, which appears to be a good thing based on his xwOBA on those batted balls. That’s not to say he’s 100% mechanically sound though (not that I would know exactly what that is but I digress). Currently, he’s on pace for a 44.7% FB% and a 19.2% LD% — the third highest and second lowest of his career, respectively — and that still-deflated LD% might be a “feel” or timing issue due in part to his hands’ tendency to drift as a pitch is coming in. Watch Seager’s hands closely in a couple examples from 2018:

Seager’s hands appear much closer to their 2016 position. His average launch angle on line drives and fly balls combined is eerily similar to last year at 29.6° but his line drive launch angle has gone down while his fly ball launch angle has gone up, which appears to be a good thing based on his xwOBA on those batted balls. That’s not to say he’s 100% mechanically sound though (not that I would know exactly what that is but I digress). Currently, he’s on pace for a 44.7% FB% and a 19.2% LD% — the third highest and second lowest of his career, respectively — and that still-deflated LD% might be a “feel” or timing issue due in part to his hands’ tendency to drift as a pitch is coming in. Watch Seager’s hands closely in a couple examples from 2018: