Ed. note: this was probably intended for a few days ago, but it just showed up, so, enjoy!

—

Determining playoff success ain’t like predicting outcomes during the regular season. Smaller sample sizes, emotions, momentum, and magical realism have been blamed for seemingly unexplainable outcomes in baseball’s postseason. Common knowledge about predicting success doesn’t add up, “shouldn’t the best teams win the World Series every year?” It might depend on what we call, “best”.

It’s not always the best regular-season teams that win the World Series; in the last 20 years only four teams that had the best record in baseball have gone on to win the World Series (20%). Even momentum heading into the playoffs doesn’t seem to amount to much World Series success either; the 10 best September records heading into the playoffs haven’t amounted to a World Series victory during the Wild Card Era[1].

Despite these results we still can’t get away from favoring the best teams every single year — after all, “nothing succeeds like success.” There is something to be said about previous playoff success within the wild-card era, and whether it is maintaining the rosters of successful teams or a cultural revitalization within these teams, previous playoff success has paid off. In fact, 13 of the last 20 years of World Series championships (65%) belong to only 4 teams: Yankees, Red Sox, Cardinals and Giants.

A new study on previous success by Rosenqvist and Skans (2015)[2] may have shed some light onto this phenomenon. Their experiment compared golfers of seemingly equal skill and ability: golfers who marginally made the cut for a golf tournament vs. golfers who marginally missed the cut for the same tournament. They found that golfers who made the cut showed an increase in performance in subsequent tournaments compared to those golfers who missed the cut. Early luck leads to increased confidence, which later leads to more success.

Success, either accidental or otherwise, seems to be contagious. Baseball, however, isn’t golf (unless you’re Brandon Belt). Baseball is comprised of teams of individuals, each with their own history of success or failure, confidence or doubt. However, using this theory, could it be the case that teams that are comprised of players with more playoff success have the confidence to do it again?

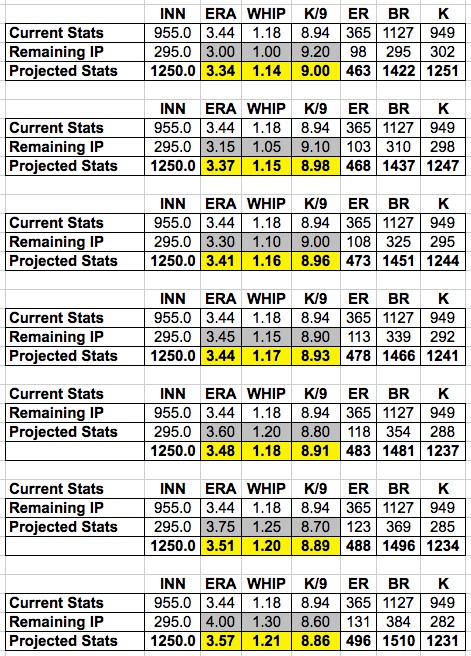

I totaled all of the playoff experience for every player on the 8 playoff teams in the ALDS and NLDS. To have contributed to previous playoff success, a player had to have played at least once during a previous playoff run (pitched at least one pitch, come in to pinch-run, come in to play defense, or taken at least one at-bat). Below, each team has an “average player profile” that defines each team’s average postseason player. The profile is comprised of the average experience and success across five variables: years that a player has contributed to a playoff team, total playoff games won with each contributed team, playoff series won with each contributed team, World Series appearances with each contributed team, and World Series victories with each contributed team.

Kansas City Royals

| Average years contributed |

Average playoff games won |

Average playoff series won |

Average World Series appearances |

Average World Series victories |

Average age

|

|

1.48

|

8.16 |

2.08 |

0.72 |

0.08 |

29.4

|

Though the 2015 Royals have carried their 2014 playoff experience with them, it’s not last year’s remaining players that are most intriguing. In some savvy acquisitions the Royals have padded their already experienced squad with some playoff warhorses. The 2015 acquisitions of Joba Chamberlain, Ryan Madson, Franklin Morales, and Jonny Gomes all come with some serious playoff success – each have a World Series ring.

Yet, despite the playoff experience added by this year’s Royals, their 2015 playoff roster doesn’t include Joba Chamberlain or clubhouse glue-guy Jonny Gomes, each with a ring. Omar Infante was also left off, who had the second-most World Series appearances across all 8 teams, tied with Matt Holliday with 3. Despite the youth-driven movement from last year’s team, the 2015 Royals are surprisingly the second-oldest team in this year’s postseason. Their age comes with some success – the average 2015 Royal has been to the playoffs, won an average of 8 games, won at least 2 series, and been to a World Series.

Houston Astros

| Average years contributed |

Average playoff games won |

Average playoff series won |

Average World Series appearances |

Average World Series victories |

Average age

|

|

0.64

|

1.56 |

0.28 |

0.04 |

0.00 |

28.3

|

Young teams with no playoff experience can play like they have nothing to lose; they’re young, they’re talented, and there’s a belief that if they’re this good now, they’ll be able to make the playoffs again in the future. It runs counter to the success-confidence-success theory, but this could be the story for the 2015 Astros who could propel themselves to an accidental World Series appearance.

The only player on the 2015 Astros to have been to a World Series is Scott Kazmir with the 2008 Rays. Overall, the pitching staff is older (m = 30.1 years old) and more successful (m = 2.27 games won) compared to their position players (m = 26.9 years old, m = 1.00 games won). This composition is counter to the 2015 Mets, who have pitching youth paired with position-player experience. The Astros are a young team; they’ll be looking to pull a 2014 Royals on the 2015 Royals.

Royals in 5

Toronto Blue Jays

| Average years contributed |

Average playoff games won |

Average playoff series won |

Average World Series appearances |

Average World Series victories |

Average age

|

|

1.12

|

3.72 |

0.80 |

0.24 |

0.00 |

29.3

|

When the majority of a team’s playoff experiences comes from a duo of former Rockies, you know two things: 1) It’s been a long time since the Blue Jays have reached the playoffs and 2) the current team lacks playoff experience. The only player who knows what it takes to win a World Series is Mark Buehrle, and apparently his late-season implosion was enough to leave him off the postseason roster. The Blue Jays sport the second-oldest average player (m = 29.3) including the oldest player in this year’s postseason to be in the playoffs for the first time – the 40-year-old R.A. Dickey. The Blue Jays join the Mets and the Astros to field a team without any players who have won a World Series.

This is the opposite of playing with accidental confidence, where a young or inexperienced team suddenly finds themselves in the playoffs and plays the game like they’ve got nothing to lose, “there’s always next year”. Well for these Blue Jays, next year isn’t a guarantee. They may not be playing with a blithe spirit of reckless abandon but the fleeting dreams of older players who may never reach the playoffs again. But who knows, maybe the exuberance of being in the playoffs for the first time is enough to spark a youthful movement? The theory disagrees.

Texas Rangers

|

Average years contributed

|

Average playoff games won |

Average playoff series won |

Average World Series appearances |

Average World Series victories |

Average age

|

|

1.60

|

7.28 |

1.56 |

0.64 |

0.08 |

28.9

|

The average Texas Ranger profile is a bit deceptive – heavily weighted by those that have previously been to the playoffs. The average Texas Ranger who has previously been to the playoffs has won 15.2 games, has won 3.9 playoff series, and has been to almost 2 World Series (m = 1.78). In fact 36% of the 2015 Rangers’ postseason roster have been to a World Series. The Rangers have very quietly maintained many of the players who got them to the back-to-back World Series’ in 2010-2011 (Lewis, Holland, Moreland, Andrus, Napoli, Hamilton).

This team will be overlooked for their lack of pitching, but their postseason success cannot be ignored. With the average Texas Ranger having nearly double the success of winning playoff series than the average Blue Jay, we might expect this series to be a cakewalk for the Rangers. Then again, it’s a five-game series, and the Blue Jays have some serious star power.

Rangers in 4.

Chicago Cubs

|

Average years contributed

|

Average playoff games won |

Average playoff series won |

Average World Series appearances |

Average World Series victories |

Average age |

| 0.92 |

3.76 |

0.92 |

0.20 |

0.12 |

28.4

|

In “the year of the rookie” it only makes sense to have two young teams representing each league in the postseason. If you removed Austin Jackson, the 2015 Cubs start to look a lot like the 2015 Astros. The pitching staff is older (m= 29.9 years old) and more successful (m = 4.73 games won) compared to the Jacksonless position players (m = 27.1 years old) and (m = 1.92 games won). The Cubs are lucky to have both a position player (David “Dad bod” Ross) and a pitcher (Jon Lester) with World Series rings, along with 16% of postseason players with World Series exposure. So, maybe the Cubs are a slightly more seasoned version of the 2015 Astros.

The Cubs are also deceptively successful in the playoffs. Despite an average of only 1 year in the playoffs, the average Cub has won almost 4 games and 1 series. Compare this to the New York Mets who have relatively the same amount of experience, but with far less success.

Between the minds of Theo Epstein and Joe Maddon are some great ideas about utilizing leadership, team chemistry, and plenty of other intangibles. Count on the Cubs to take advantage of the balance between youth and experience during this year’s playoffs.

St. Louis Cardinals

|

Average years contributed

|

Average playoff games won |

Average playoff series won |

Average World Series appearances |

Average World Series victories |

Average age |

| 2.64 |

14.6 |

3.56 |

0.84 |

0.32 |

28.6

|

The average Cardinal has some serious playoff success. The average Cardinal has been to the playoffs at least 2 years, won at least 14 games, and won at least 3 series. The 2015 postseason Cardinal has not only been to the World Series, but 25% of the 2015 postseason Cardinals have won a World Series; all of this playoff success and still a relatively young team. The Cardinals have the 2015 player with the most postseason experience in Yadier Molina, who has appeared in 4 different World Series and won 2 of them. The saddest part about the 2015 Cardinals is the absence of Randy Choate, who won a World Series with the 2000 Yankees (2 World Series rings in 16 years would have been a cool story).

The Cubs might give the Cardinals some fits, but the theory says that the Cardinals shouldn’t have a problem disposing of the Cubs. Count on the Cardinals making it back to the World Series.

Cardinals in 4

New York Mets

|

Average years contributed

|

Average playoff games won |

Average playoff series won |

Average World Series appearances |

Average World Series victories |

Average age

|

| 0.96 |

2.32 |

0.40 |

0.04 |

0.00 |

28.0

|

If there are counters to the success-confidence-success theory it’s the 2015 Mets, who are basically the 2010 San Francisco Giants: loaded with young talented pitching and complemented with older, experienced position players. The Mets are in fact the youngest of the 8 playoff teams, though their youth comes with a price. In fact, the Mets’ pitching staff is so young and inexperienced, if you removed Bartolo Colon, you’d only have 1 pitcher with playoff experience (Tyler Clippard with the hapless 2012 and 2014 Nationals).

Quite similar to the 2010 Giants, the only player on the 2015 Mets to have won a World Series is Juan Uribe (2005, 2010) who did so with the Giants in 2010, yet due to injuries isn’t on the playoff roster. The Mets will have some decent playoff success with Curtis Granderson, David Wright, and Michael Cuddyer who can describe to young players what it’s like to lose in the playoffs. The only player to have even been to a World Series is Granderson when he was on the Tigers who lost to the Cardinals in 2006.

Los Angeles Dodgers

|

Average years contributed

|

Average playoff games won |

Average playoff series won |

Average World Series appearances |

Average World Series victories |

Average age |

| 2.04 |

6.64 |

1.28 |

0.24 |

0.08 |

29.6

|

Chase Utley + Jimmy Rollins + Good Starting Pitching = 2007-2011 Philadelphia Phillies. The Dodgers are hoping they get the 2008 version, though by the looks of things, it may resemble more of the 2010 version. The average Dodger has been to the playoffs, won a few games, and won at least 1 series. It’s really a smattering of success and experience despite being the oldest team in 2015 postseason (m = 29.6 years old).

Their playoff success says that the Dodgers should be able to handle the Mets, though the real test will be whether this older group of players will take to the leadership and previous success of Utley and Rollins. If the Dodger players are smart, they’ll humble themselves as much as possible, hone in, and play as a team.

Dodgers in 4

Conclusion and Caveats

- Yes, skill and ability is obviously something to take into consideration. Though, players who are highly skilled tend to find themselves on more successful teams, so the two may be related. The same can be said for age: the older you are, the more playoff experience you’re likely to have. However, if you look at this year’s teams, average age and average playoff success don’t seem to be related at all.

- Yes, in recent memory, the 2010 Giants and the 2014 Royals have been successful in the postseason despite a lack of playoff experience and success. However, in the playoff era, how many have actually won the World Series? Few come to mind.

- Yes, skill seems to be valued more that experience. Most managers tend to stick with their highest-performing players, and you can’t blame them. However, if this theory holds true, maybe you can blame them. The second season might benefit from previous playoff success. The counter to this is to picture a 2015 postseason team with 67-year-old Johnny Bench, 84-year-old Willie Mays, and “Mr. October” 69-year-old Reggie Jackson (all have some serious playoff success, right?). Recall from #1 that skill and ability obviously count, but the theory states that previous success might count too.

[1] http://www.sportsonearth.com/article/152528108/mlb-playoffs-momentum-best-septembers

[2] Rosenqvist, O. & Skans O.N. (2015). Confidence enhanced performance? – The causal effects of success on future performance in professional golf tournaments. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 117, 281-295.