Finding the Mets a Catcher

Having started the year at 10-1, the Mets’ season is certainly going swimmingly. This team could realistically make a playoff run, which was something no one seemed to be certain of prior to the season. The hope for Mets fans is that the team’s decision makers in the front office don’t mess this up, or miss an opportunity to make sure this team maximizes its potential.

Mets ownership and management has been nothing short of infuriating in recent years, whether that has meant mishandling issues with injured players, failing to spend sufficiently on payroll despite being in the gigantic New York market, and countless other reasons. It seems reasonable to expect the team to be more ambitious in signing star players, or at least keep the homegrown stars healthy on the current team. The team’s treatment of medical issues are significant enough to justify their own post altogether, but exploring that will be left for someone else, or investigated another time.

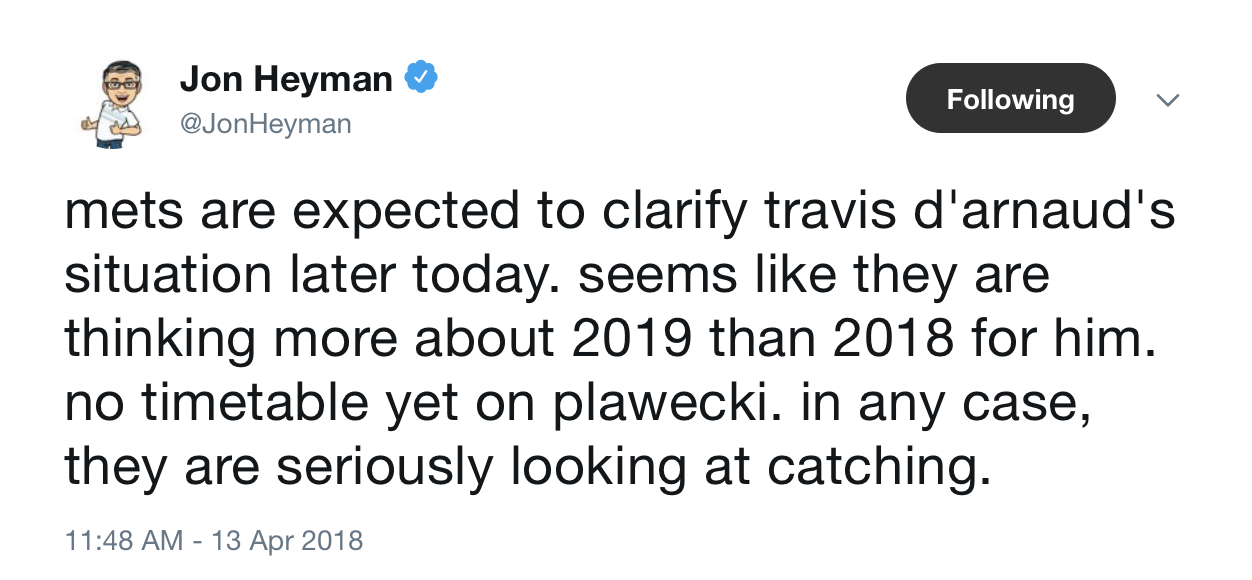

Kevin Plawecki just fractured his hand, while Travis d’Arnaud is set to have Tommy John Surgery next week. The team needs help at Catcher, and if management wants to make sure this team remains in contention, they will trade for a useful backstop. Jon Heyman confirmed that the team is indeed interested in upgrading at the position:

Who could the Mets acquire via trade? The elephant in the room is J.T. Realmuto, an elite catcher who’d be an immediate upgrade over even the injured d’Arnaud and Plawecki long-term. He is also represented by CAA , like many prominent Mets stars (DeGrom, Syndergaard, Cespedes), making a trade for Realmuto seemingly more likely. In reality though, he is still on the DL for the Marlins, and the asking price in a trade for him would be far too steep for the Mets to be able to meet. Their farm system lacks the impact talent needed to land a player of Realmuto’s caliber, and trading useful major leaguers is effectively not an option for a contending team.

Could the Dodgers be convinced to deal Yasmani Grandal? Considering the performance of Austin Barnes at the end of last season, and their faith in him throughout the playoffs — It would not seem completely unreasonable for them to be interested in trading Grandal. Though for a team with serious championship aspirations, keeping around two starting caliber star-level catchers is justifiable. Add in the fact that Grandal has already been worth 0.7 WAR, and one realizes that the Dodgers very likely wouldn’t be interested in a swap.

A team can lose a catcher anytime to a concussion, or injury as a result of a foul tip, among other potential risks that are inherently a part of playing the position. Given this possibility, it’s reasonable to see why the Dodgers are content splitting playing time between two very talented backstops. The Mets are all-too-aware of this reality, with both their regular catchers set to miss significant time with injuries already this season.

If the team wanted to kind of take a lottery ticket on a Catcher, they could trade for Luke Maile, a strong defensive catcher who has hit surprisingly well to start the year. Defensively he was worth 4.9 runs in 46 games in 2017, and he has four hits with exit velocities over 105 mph already this year. If he can hit better than he has previously, Maile would be a great buy-low candidate for the team. He is blocked by Russell Martin in Toronto, so he could likely be acquired by the Mets pretty easily.

A strong option for the team, is the Cardinals’ Carson Kelly. Though he is seen as more of a defensive catcher, his 120 wRC+ in Triple-A last year illustrates that he is ready for regular playing time in the big leagues. He hasn’t hit at all in his brief major league time, yet has never gotten an extended look at the level. Being blocked by Yadier Molina, who is signed to a long-term extension, has left no real opportunity for Kelly to get the regular playing time he needs to develop as a hitter.

The scouting reports indicate that the 23-year-old has average hitting abilities, which coupled with his above-average to plus defense, should intrigue the Mets. The young backstop had an average pop-time of 1.96 seconds last season, which ranked 23rd among all major league catchers. By comparison, Travis d’Arnaud ranked 78th with an average pop-time of 2.06 seconds, while Plawecki ranked 86th with a time of 2.08. The Mets acquiring Kelly would be an upgrade for their defense at Catcher, which would be a welcome change for their pitching staff.

The Cardinals have to realize that Kelly doesn’t have a real chance to play regularly anytime soon, and the Mets know they have an obvious need behind the plate. A trade between the two teams seems like a good idea for both sides, considering each team’s situation. The latest Fangraphs prospect reports for the Cardinals in November of 2017 placed a 50 FV on Kelly, so to get a sense of what his trade value likely is, that will be used as the primary indicator.

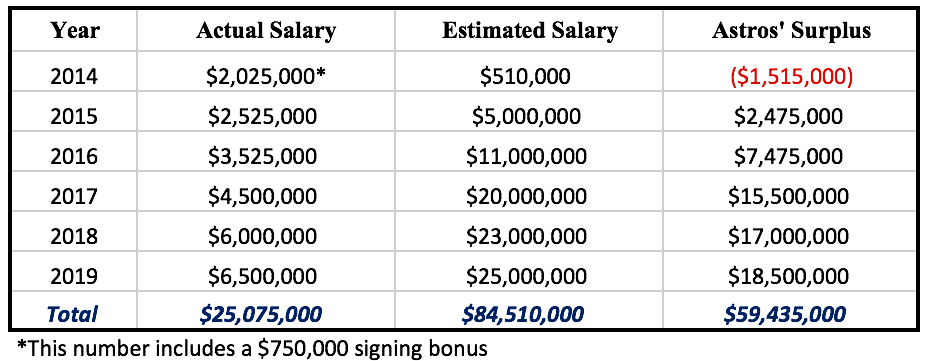

Basically, he is expected to be a 2 WAR player per season and would be controlled through the 2023 season assuming he played the majority of 2018 in the major leagues. So this is a roughly 12 WAR player, over the course of the six years he would be under team control. As a contender, the Mets would not be interested in trading any of the players on their major league roster, so any trade would almost certainly involve sending minor leaguers to the Cardinals in return for Carson Kelly.

Mets pitching prospect Justin Dunn would seem to be a sufficient return in a trade with St. Louis, as he also received a 50 FV rating from Fangraphs prospect analyst Eric Longenhagen. A reliever initially at Boston College, Dunn started some games at the end of his final spring with the Eagles, before being selected in the first round by the Mets in the 2016 draft. He already has a strong Fastball / Slider combination in addition to a developing Curveball and Changeup, all pitches that give him the potential to have a formidable four-pitch mix. His strong pitching at High-A this season has been encouraging, and he would be a welcome future addition to the Cardinals’ 15th ranked MLB rotation by WAR.

This would be a trade to benefit both teams and would improve the future outlook of the Cardinals while helping the Mets shore up the catching position long-term. If the Mets are really committed to winning and doing so with consistency — Trading for Carson Kelly would be a strong option for the team. After all, Syndergaard and deGrom won’t be around forever.

All Data in this article was taken from Fangraphs, Statcast, and Baseball Prospectus.