Going the Other Way

Ryan Howard doesn’t like infield shifts. I’m not making this up, or just surmising it. He said so after recording four outs on balls that probably would have gotten through an unshifted infield:

“No, I don’t like it at all,” said Howard, who has grown accustomed to seeing four infielders on the right side of the infield when he steps to the plate. “That’s four hits. I mean, again, it’s nothing that I’m doing wrong, I’m hitting the ball hard. It’s just right at guys playing shifts. So, all you can do is continue to swing.”

Back in May, Craig Edwards noted that Jason Kipnis had a rotten 2014 (86 wRC+), likely in part due to an oblique injury in April that affected his performance all year. Kipnis’s 2014 was characterized by an increase in grounders, weak contact, and pulled balls. This season, of course, he’s been a monster (164 wRC+ through June 21, fourth in the American League), in part because, with a healthy oblique, he’s pulling less.

Why, fans and sportswriters ask, can’t more hitters do what Jason Kipnis has done by going the other way? Proliferating infield shifts are taking hits away from the likes of Howard, David Ortiz, and Mark Teixeira. So why don’t those players just hit the ball where they ain’t? I’m not talking about bunting. This is just about pull-happy hitters go the other way, guiding batted balls to the opposite field.

I think pretty much everyone reading this knows the answers why. First, infield shifts are effective against grounders and soft liners, and a batter with fly ball tendencies hits the ball over the shifted infielders more often than not. The Indians’ Brandon Moss is a pronounced pull hitter (48% of batted balls hit to right field) who also hits the ball in the air a lot (0.67 ground ball/fly ball ratio, fifth lowest in the majors). So he goes to the plate trying to hit over the shift. Second, and more significantly, I think, hitting, one hears, is hard. Granted, I never played professional baseball like the people on sportstalk radio who insist that Chris Davis would be a much more productive player if he’d just shorten his swing and go with where the ball’s pitched, dumping singles through the vacated space on the left side of the infield. Changing one’s approach to the plate would seem to have a concomitant risk of decreased production.

But players can and do make adjustments. And, as the case of Kipnis illustrates, those adjustments can lead to better outcomes. How often do batters rely less on pulling the ball, and what does it do to their performance?

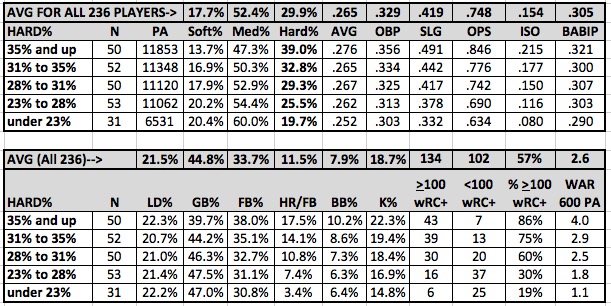

To answer this, I looked at every batter who was a semi-regular (which I arbitrarily defined as compiling two-thirds the plate appearances necessary to qualify for the batting title) in 2014 and 2015. (My criteria worked out to 334 plate appearances in 2014 and, depending on the team, 140 or so plate appearances in 2015.) There were, through games of June 21, 186 such players. I calculated their “pull tendency” by subtracting the percentage of balls they hit to the opposite field from the percentage they hit to the pull field. Ryan Howard, for example, has a pull tendency of 31.9% this year, having hit 48.8% of batted balls to right field and 16.9% to left. I then subtracted each player’s 2015 pull tendency from his 2014 pull tendency to arrive at the change, i.e. how much more he’s going the other way in 2015. To determine the effect of the change, I calculated the change in the player’s wRC+ from 2014 to 2015 as well. Here are the 15 players who have most dramatically changed from pulling to going the other way in 2015:

Well now. That’s quite a mix. There’s probably the 2015 poster child for going the other way, Mike Moustakas, leading the way with a vast improvement in wRC+. But the median wRC+ change on the list is negative five points–players who are pulling markedly less are having less, not more, success at the plate. Seven of the fifteen players are having a better year in 2015, while the remaining eight aren’t. Of course, as with any list like this, there are caveats. The change for Moustakas is evidence of a well-executed plan. But you can make a pretty good argument that Carlos Ruiz is pulling less because,at 36, he can’t get around on pitches as he used to, and a fairly airtight argument that Victor Martinez is pulling less because he’s been playing hurt. Danny Santana, he of the .405 BABIP in 2014, was at the top of the 2015 regression list regardless of where he’d hit the ball–a lot more of them were bound to find their way into fielders’ gloves. Josh Harrison is coming off a career year. Alcides Escobar, who cares, the guy’s an All-Star Game starter! But if there’s a pattern there of pull less, hit more, I’m not seeing it.

How about players who have done the opposite–in the face of shifts, they’re pulling the ball more now than they did last year? Here’s the list:

Another mixed bag, with a negligible median change in wRC+ (-2 in this case; seven players doing better, eight doing worse). Pulling the ball more certainly hasn’t hurt Todd Frazier (leading all third basemen in wRC+) or the first two second basemen on the list. By the same token, it’s one of many symptoms of the woes of Robinson Cano (discussed in length by Jeff Sullivan here). As with players pulling less, if there’s a pattern here, that pulling more has a systemic impact, I’m not seeing it.

Admittedly, there are limits to this type of analysis. Hitting isn’t just a product of where the ball is hit. It’s affected by whether it’s hit on the ground or in the air, whether it’s hit hard or soft, whether it’s hit by a healthy batter or an injured one, whether it’s hit off a fastball or an off-speed pitch, and whether it’s hit at all or missed. I looked only at the first comparison: pulling the ball vs. going the other way, because that one characteristic has been harped on by fans and some in the media. And the data indicate that changing one’s approach–going from pulling to hitting to the opposite field, or, for that matter, vice-versa–does not appear to have a systemic change in batting outcomes. It works for some players. It doesn’t work for others. For every Mike Moustakas, it seems, there’s a Todd Frazier, or a David Peralta. When Ryan Howard hits four grounders to Kolten Wong in short right field, turning singles to right into 4-3 putouts, it may frustrate him, but that’s not to say that trying to hit the ball to left wouldn’t frustrate him even more.