Miguel Sano Is the Three True Outcomes Hitter We’ve Been Waiting for

The idea of a “three true outcomes” (TTO) hitter, a batter whose plate appearances typically end in a walk, strikeout, or home run, is nothing new — Rany Jazayerli proposed the idea all the way back in the forgotten year of 2000, when the Backstreet Boys dropped their latest hit album “Black & Blue” and Dora the Explorer debuted.

In that article, Jazayerli describes how the Rob Deer Fan Club (of which I am a card-carrying member) had just discovered the newest prophet for the gospel of TTO — Russell Branyan, who seemed poised to demonstrate the TTO philosophy on the big stage, had just been named the Indians’ top prospect by Baseball America.

While Branyan lived up to the TTO promise, it appears as though he may have been a false prophet — Branyan struggled to stay in a starting role, jumped around the majors for a bit, and never made a significant impact while he played.

Worry not, for the Rob Deer Fan Club (or as it is otherwise known, the RDFC) was not without a champion during the 2000s. I present to you our holy savior, Adam Dunn. Dunn surpassed Deer as the king of the TTO, finishing his career with a TTO% (HR+BB+SO/PA) of 49.9% to beat Deer’s 49.1% figure. Dunn clubbed 462 home runs, drew 1317 walks, and struck out 2379 times — finishing 35th, 42nd, and 3rd respectively all-time despite only playing 14 seasons. He out-Deer’d Deer!

Nevermind the fact that the RDFC was blessed with the presence of Jack Cust, who set the TTO% single-season record in 2007 with a TTO% of 58.2% (among qualified players). Or Jim Thome, who in his quiet and humble way, finished his career 4th in TTO%. How about Mark Reynolds? Or Ryan Howard? Or Pat Burrell? All of them are worthy disciples of the school of TTO.

But it has been years since we’ve seen someone live up to the TTO promises of Mark McGwire’s 1998, where he finished with a TTO% of 56.8% and a wRC+ of 205. Why did the gods of TTO forsake us?

Mercifully, our prayers have been answered, in the form of Miguel Sano. Sano is on pace to the be the first player since McGwire to finish with a TTO% of 55% or more and with a wRC+ of 150+. In fact, Sano is on pace for the highest TTO% ever: 59.4% entering Monday.

This raises the question: how is Sano doing this?

Sano has a few things going for him, namely his contact. Sano is seemingly no longer hitting balls softly — end of story. Not only is Sano posting the lowest Soft% ever (3.9%, besting Joe Mauer and Briant Roberts’ 2006 figures of 5.1%), but he’s also second in the majors in Hard%. Sano is leading the average exit velocity charts by 3.6 MPH — our lord Rob Deer must be smiling down upon him.

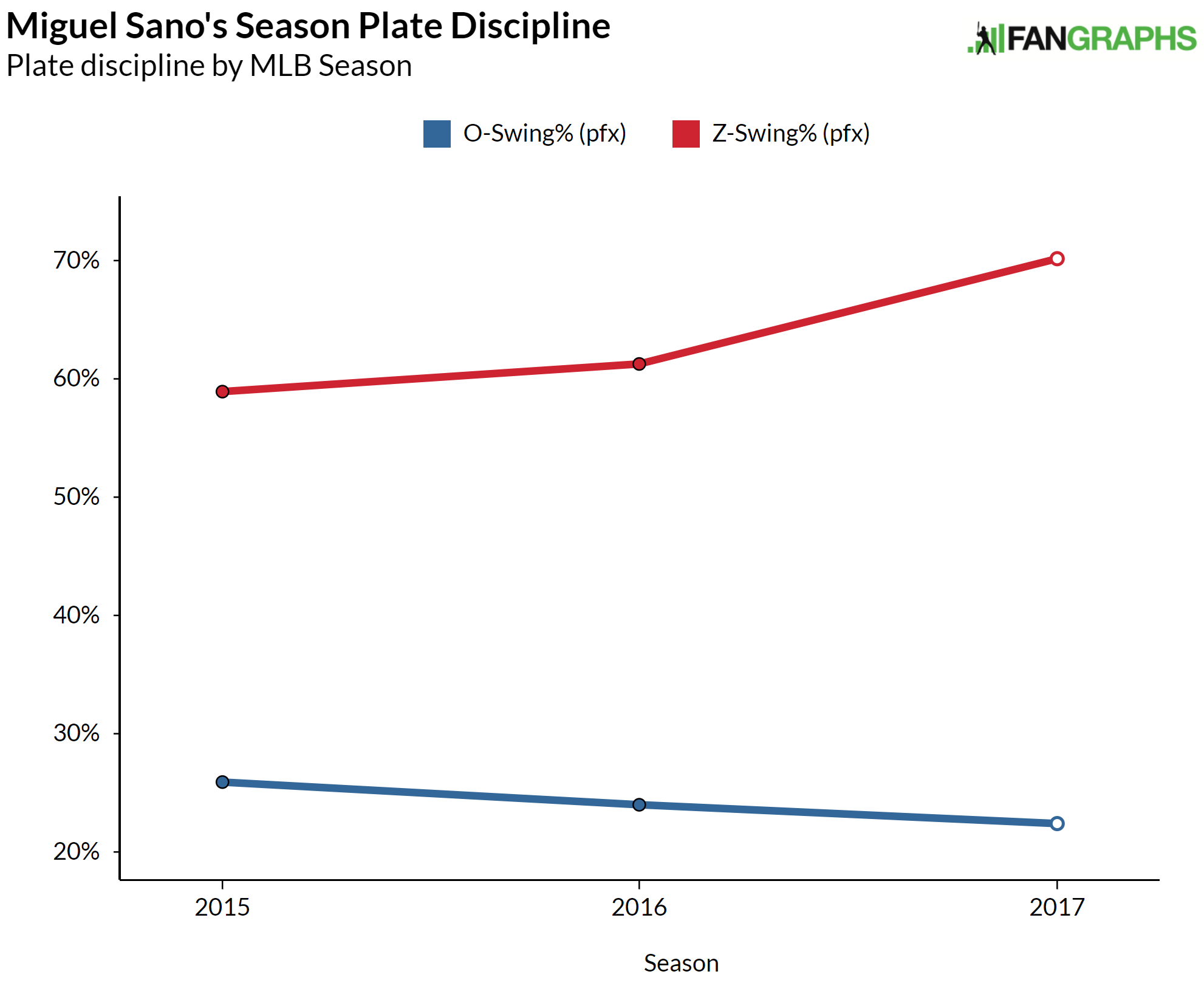

Sano’s plate discipline has also quietly improved. This season represents the high mark for his Z-Swing%, and the low mark for his O-Swing%. This is crucial to executing the TTO philosophy — by swinging less at pitches out of the zone, Sano draws more walks, and by swinging at pitches in the zone, Sano avoids taking strikes.

Sano is still striking out at the same rate that he’s done in his career — his 35.2% figure for 2017 is roughly in line with his career 35.7% figure. But by improving his discipline, Sano has managed to bolster the weakest portion of his TTO game — walks. Sano has seen his BB% skyrocket from 10.9% last season to 18.2% this season. Furthermore, Sano made an adjustment to his swing this offseason that may have sent his swing from one of the hardest in the game to the hardest in the game — by miles.

We are only a quarter of the way through the season, which means that we still have three-quarters of the season left to see players regress, get injured, fall into old habits, etc. But it also means that we’ve seen Sano sustain being the best TTO hitter since McGwire for an entire quarter of the season.

Sure, Sano is hitting with a .463 BABIP and a 28.6% HR/FB%. But he’s also making the best contact of anyone that FanGraphs has ever measured — so such a crazy high BABIP and HR/FB% might not be as unsustainable as you think.

Regardless of how Sano finishes the season, I and my fellow Rob Deer Fan Club members are thanking the holy trinity of Home Runs, Walks, and Strikeouts (hallowed be thine names) for blessing us with Sano, who stands to be a treat to watch for the foreseeable future.