It’s Not Too Late to Give Bryce Brentz a Shot

*Apologies for the bad writing, as this is my first-ever community post on FanGraphs.*

At the time of this writing, it’s been seven days since rosters expanded in the major leagues. Still, the International League (AAA) home-run leader has yet to appear in a major-league game season. Since the 2000 season, there have been three International League home-run champions that had not appeared in a major-league game that same season. Bryce Brentz, leading that league with 31 home runs and winner of the Triple-A Home Run Derby, is about to be fourth.

The Red Sox of the old days had the reputation of being offensive powerhouses by working long at-bats and possessing big power in the middle of the lineup. This year, it’s been quite the opposite. Red Sox pitching has been absolutely amazing this season; the pitching WAR is tied for second place (with the Dodgers) while also having the fourth-best ERA in the majors at 3.76 ERA. Compared to how great the Red Sox pitching is, the hitting is bad. REALLY BAD. Their pitching and hitting are night and day. It’s well documented that the Red Sox aren’t hitting for power this year, sitting dead last in the AL with only 146 home runs. Perhaps teams don’t need to hit home runs to be productive? The advanced metrics say otherwise. Out of all qualified players, the Red Sox batter with the highest wRC+ is Dustin Pedroia who has a 106 wRC+, and 2016 MVP runner-up Mookie Betts is running a 101 wRC+. All in all, the Red Sox offense has been below average this season. The emergence of Rafael Devers and the spark that Eduardo Nunez has provided to the Red Sox have both softened the blow, but there still appears to be a glaring weakness.

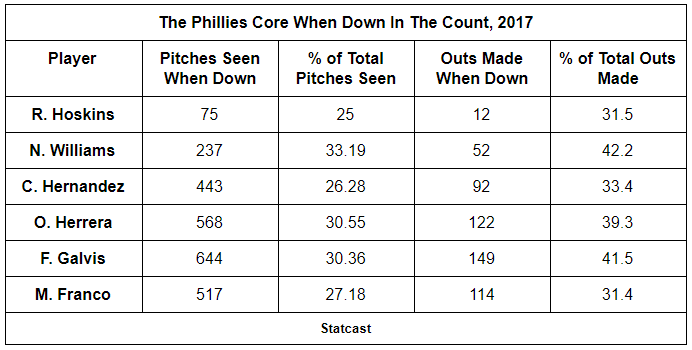

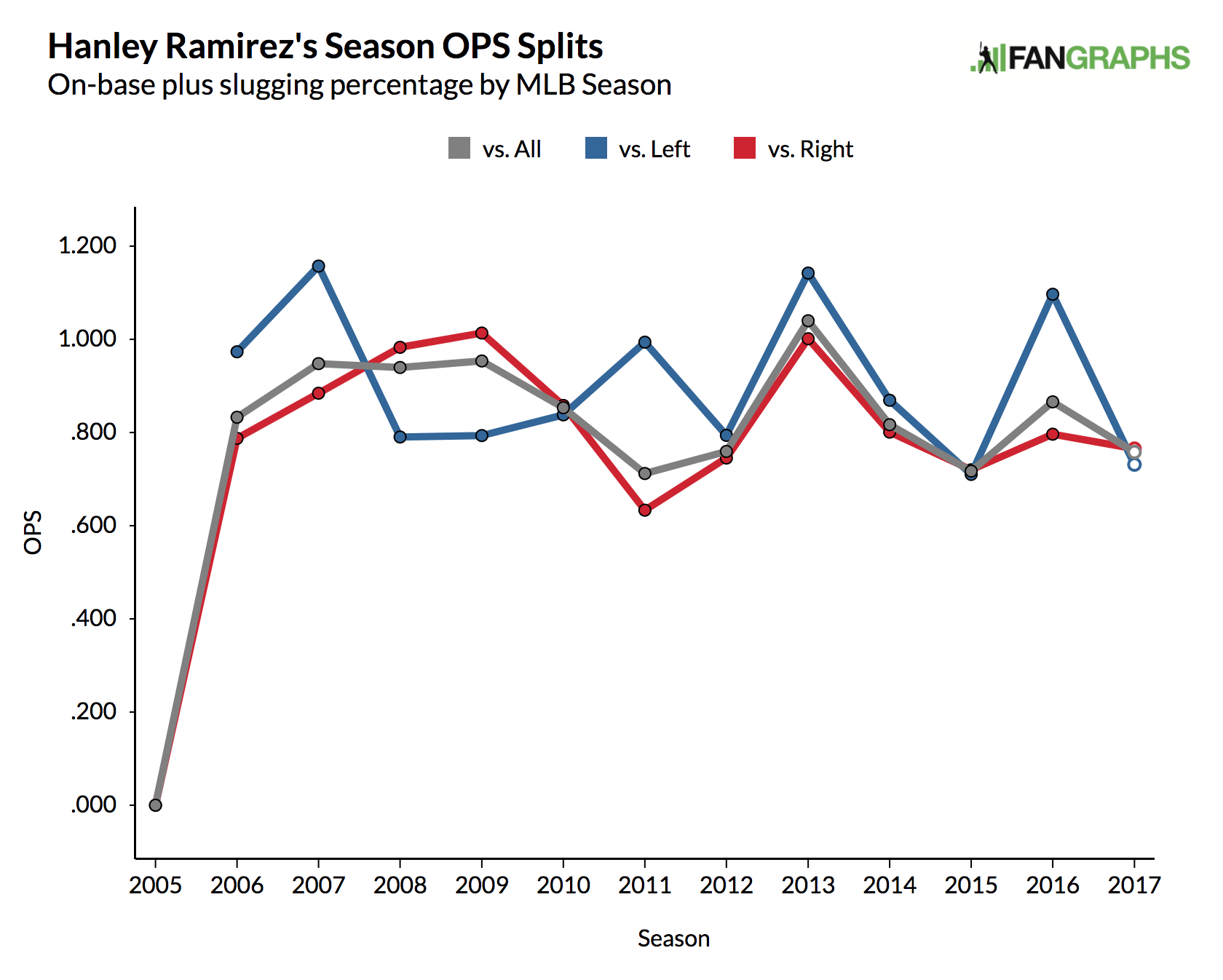

In the absence of David Ortiz, Hanley Ramirez was supposed to step up and become a middle-of-the-order power threat. What’s inexcusable is his performance versus lefties this year. As someone who’s destroyed lefties his entire career, he’s suddenly slashing .194/.312/.419 against lefties in 2017. His career OPS/wRC+ vs. lefties is .902 OPS and 138 wRC+ respectively.

HanRam has been having one of his worst seasons hitting-wise versus lefties. Despite insisting that he will improve against lefties, Red Sox fans have yet to see the results come out.

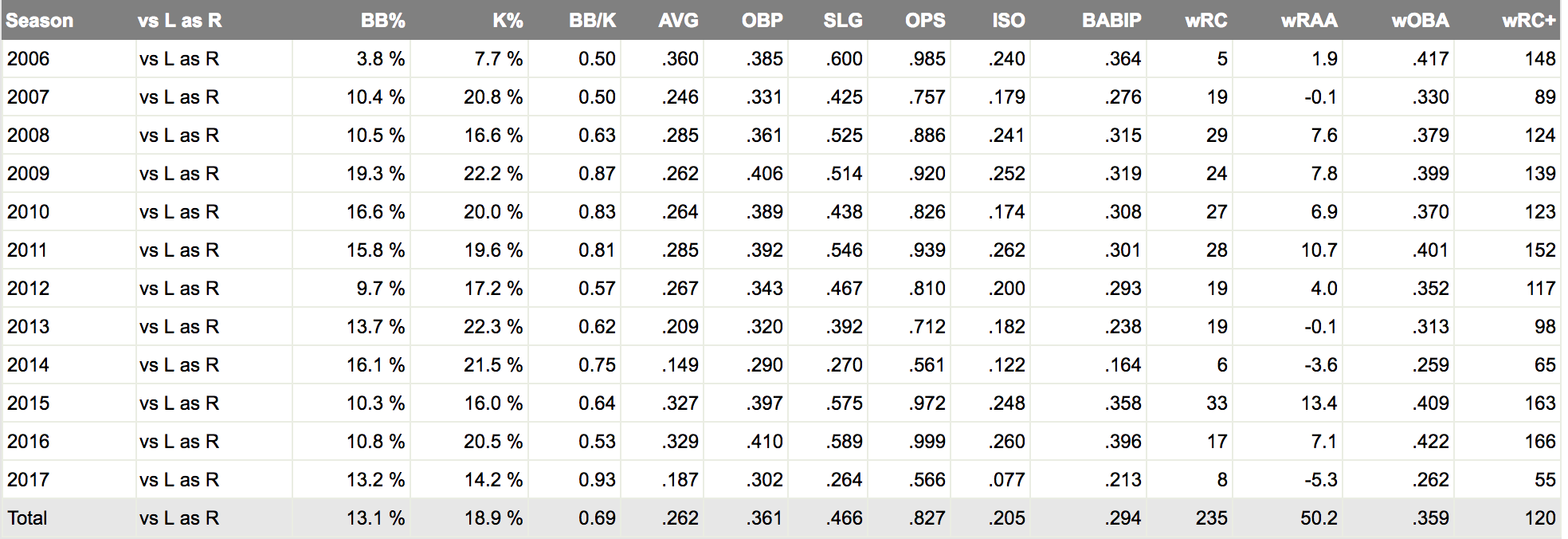

Another factor is Chris Young’s performance. Chris Young was brought to Boston to club lefties. He’s always been able to hit them, and his splits against lefties prove just that.

Discarding 2014 and this current season, that chart is a thing of beauty. Chris Young’s performance this year has been concerning; he hasn’t had an RBI since August 6! Chris Young was a player who was specifically brought onto this roster for the specific purpose of facing tough lefties. He is having his worst season hitting lefties yet. As of right now, he is batting only .184 against lefties this season with one home run, four extra-base hits, and four RBI.

The Red Sox need Bryce Brentz. Brentz certainly has the prospect pedigree, being drafted by Red Sox in the first round of the 2010 Major League Baseball Draft out of South-Doyle High School. Once rated as the No. 5 prospect in the Red Sox system, he stood out with his plus raw power. FanGraphs’ Kiley McDaniel had this to say about him a few years back:

“Brentz has easy plus raw power from the right side and is a solid athlete, but it doesn’t translate to defense, where his fringy arm limits him to left field. There’s some holes, lots of swing and miss and trouble with spin from right-handed pitchers, but also 20-25 homer power with a floor of a solid platoon bat.”

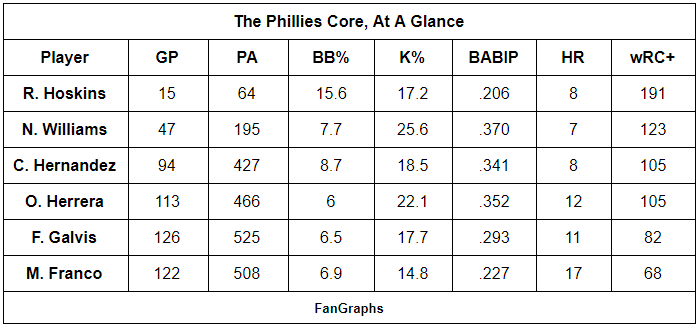

The key word here is “solid platoon bat,” something he’s finally evolved into this year. This year, down in Triple-A, when facing left-handed hitters, Brentz was hitting .279 with nine home runs, 25 RBI, and 17 walks. His OPS against lefties is 391 points higher than Chris Young’s OPS in the majors this season (.957 OPS). Rhys Hoskins, who took the majors by storm, was the only player ahead of him in the IL in terms of wRC+.

Brentz had worked with PawSox hitting coach Rich Gedman this past offseason, which has suddenly changed him into someone who destroys left-handed pitchers and is at least passable against righties. By introducing a toe-tapping procedure to Bryce Brentz, Gedman has turned him into a major home-run threat. I think it’s time to believe that after 6+ seasons in the minor leagues, Bryce Brentz finally has things figured out.

The basis behind why Dave Dombrowski won’t call up Bryce Brentz is, to say the least, questionable.

Dave Dombrowski said IL HR champ Bryce Brentz willl not get callup from Pawtucket. Brentz hit 31 HR but no 40-man roster spot available.

— Nick Cafardo (@nickcafardo) September 4, 2017

No 40-man roster spot available? C’mon. Off the top of my head, I could name off a few minor leaguers who don’t deserve this spot over Brentz. Most notably, the walk machine himself, Henry Owens. Owens was sent down to Double-A to work on mechanics, but instead, he’s walking 8.68 batters per 9. Ben Taylor, who made the Opening Day roster for the Red Sox, has had considerable minor-league success, but the results haven’t translated to the majors. He’ll most likely end up as a career middle reliever or minor-league journeyman. Sure, these players have their uses, but they don’t deserve their spots as much as Brentz does. After his hard work in the offseason, his performance needs to warrant him a 40-man spot. Additionally, after Chris Young becomes a free agent next year, Brentz can serve as the fourth outfield for the Red Sox in 2018. If the Red Sox don’t add Brentz to the 40-man by the offseason, he’ll become a free agent. It’s almost guaranteed that a team such as the Athletics or the Reds would be willing to give him a chance.

There’s another problem. At the moment, the Red Sox really lack good pinch-hitters. When your best hitters off the bench are Brock Holt, Sandy Leon, Rajai Davis, etc, the outcome looks really bleak. Brentz is a minor-league veteran who is a power threat off the bench, something the Sox currently lack. His career hasn’t progressed much (until now at least) since he shot himself in the leg during the spring training of 2013. If fact, if you go to some online forums, his spring-training incident has created tons of puns that have to with guns; the former top prospect had become a joke. Similar to the rest of the “comeback” stories (such as Rich Hill, Eric Thames, etc) that fans have loved to watch in recent seasons, the story of Bryce Brentz should warm the hearts of fans.

Something else stands out. During the Red Sox’s recent 19-inning game, this tweet was sent out. While it may have been mostly a joke, it really exemplifies the lack of power the Red Sox have.

Brentz would have already homered this inning

— Red Sox Stats (@redsoxstats) September 6, 2017

This really speaks about the Red Sox offense. Bryce Brentz is the spark plug that they need.

As seen by the Nationals calling up Victor Robles just the other day (considered late), the Red Sox certainly still have time to call up Bryce Brentz. If any Red Sox personnel is reading this, the rest of Red Sox Nation and I have this to say to you: “Hey, It’s worth giving Brentz a shot.” He’s deserved it.