Let me start off by pointing you to this excellent article recently penned by eyesguys1 in which he also analyzes 2016 Robbie Ray. I write this now not to steal his thunder, but to report some pretty interesting Robbie Ray trends I’ve discovered (and because I was almost done with this when I saw his article).

Robbie Ray put together a pretty successful rookie campaign last year — he pitched 127.2 innings with a 3.52 ERA to go along with a 3.53 FIP and 2.1 WAR. It’s not going to blow anyone away, especially considering last year’s rookie class, but it was a good season nonetheless.

He’s currently sporting a rough 4.69 ERA and 3.96 FIP, way up from last year’s totals. He’s ramped up the velocity on all his pitches except the sinker, so you would think he’d be doing better than in 2015, or at least not a full run worse.

| Robbie Ray Velocity Increase |

|

2015 |

2016 |

| Four-Seamer |

94.22 |

94.78 |

| Sinker |

93.70 |

94.39 |

| Changeup |

84.87 |

87.42 |

| Slider |

83.37 |

85.87 |

Likewise, his K-BB% (one of the best in-season performance predictors) has gone up. While he has walked 9% of batters he faces, his 25.6% strikeout rate is good for 17th among qualified pitchers. What’s making the difference? Home runs.

It’s fair to say he’s had a homer problem this season. His HR/FB rate is a lofty 15.8%, up nine points from last season, and it’s worth noting that his xFIP has therefore improved. His .358 BABIP appears to indicate that he’s been unlucky, but Andrew Perpetua’s xBABIP formula says that his expected BABIP is still a bit high at .323. What gives?

His platoon splits give us a clue, because they’re rather striking. Left-handed hitters have a .282 wOBA against him, while right-handers are crushing him to the tune of a .365 wOBAA. He had somewhat of a platoon split last year, but it wasn’t anything like this. He’s actually gotten better against lefties by almost the same degree as he’s gotten worse against righties. Why?

Against lefties, he’s been nothing short of dominant. He’s throwing mostly the same mix of pitches against them as he did last year (mainly the four-seamer and slider, with some sinkers thrown in) yet his wOBAA is down to .282 from .309 in 2015. His numbers versus lefties may be nothing more than randomness associated with small sample sizes since he has faced only 93 of them this season (but still only 141 last season). It’s not beyond belief that a left-handed pitcher is doing well against left-handed hitters, especially when you consider his strikeout and walk numbers. He has struck out 28% of the left-handed hitters he’s faced and walked just 5.4%, so his K-BB% is 22.6% (up from 17% last year). Plus, his home-run problem isn’t so bad for left-handers as he sports a close to league average 11% HR/FB rate. Since Ray hasn’t faced many southpaws this year, it’s harder to know what exactly he’s doing, if anything, to improve against them. What jumps out the most is that he’s getting significantly more whiffs on the slider and sinker, so that could explain the increase in strikeouts, as could the uptick in velocity. Regardless, K-BB% is one of the best in season predictors available, so he’ll likely continue doing well against lefties going forward, even if he isn’t dominant.

Right-handers are where he’s struggling. Though his K-BB% against them hasn’t been bad at all (14.8%), he’s given up a rather high 16.4% HR/FB rate versus righties (likewise, his xFIP is a bit lower). This represents a bit of a homer problem, especially considering he only had a 7.1% HR/FB RHH split last year. He’s been tinkering with his pitch mix against opposite-handers, so perhaps there’s a clue there. Take a look at his home-run rates for balls in the air (both fly balls and line drives) for his four main pitches (excluding the curve) both this season and last from Brooks Baseball:

| Home Runs on Balls in the Air |

|

Four-Seamer |

Sinker |

Changeup |

Slider |

| 2015 |

3.03 |

3.57 |

0.00 |

12.50 |

| 2016 |

7.69 |

11.76 |

25.00 |

11.11 |

While he’s given up some home runs on the four-seamer, the main culprits are the sinker, slider, and changeup. The most striking example is the changeup, which leaves the yard 20% (!) of the time when it’s hit in the air. If you think about it, it makes sense that a changeup hit in the air might often leave the yard, but I couldn’t find many with a HR rate on it like to Ray’s.

Bluntly put, his changeup has been bad. According to the pitch-type linear weight leaderboards, he’s had the league’s worst changeup by wCH at -7.3 and the fourth worst in wCH/C. (Something interesting: second-worst in wCH went to fellow D-Backs starter Patrick Corbin.) He threw his changeup about 13% this April and increased that to 15% in May. The results weren’t pretty; righties posted a .466 wOBAA in April and .330 wOBAA in May against his change. For a pitch typically with reverse platoon splits this is not good, especially considering righties’ wOBAA (on a month-by-month basis) against it peaked at .312 last year. He’s been locating it down and out of the zone, and that’s precisely where it’s gotten hit hard. It’s been getting more whiffs and ground balls, but when it is hit in the air, it’s gotten blasted (like many of Ray’s pitches).

Thankfully, through his past four starts he’s ditched the change completely, instead leaning more heavily on the four-seamer and slider. He did the same thing towards the end of last season, so maybe it’s gone for good this time. He changed his change this year, but righties simply aren’t buying it.

But the changeup isn’t the only pitch he’s played with. Last season saw a steady trend where Ray threw the four-seamer less and sinker more as the season went on. That trend continued into early June of this season. In fact, save one start against San Diego, he threw his sinker significantly more than his four-seamer against right-handers (he doesn’t throw it much to lefties) in four starts from mid-May to mid-June. Before and after this period he threw primarily the four-seamer, so dividing up his season into three periods reveals some interesting trends.

| Robbie Ray’s 2016 Sinker Against RHH |

|

April 8-May 10 |

May 11-June 5 |

June 6-June 27 |

| Four-Seamer % |

45.31% |

27.43% |

54.64% |

| Sinker % |

24.41% |

40.90% |

23.56% |

| BIP% (SNK) |

14.88% |

19.23% |

20.41% |

| GB% (SNK) |

36.84% |

40.00% |

45.00% |

| wOBAA (SNK) |

0.486 |

0.401 |

0.447 |

He’s been getting progressively more ground balls as the season goes on, and more sinkers are being put into play. Looking at his location, he spotted it further up and out of the zone away from right-handers. In that first period, he gave up seven walks in 20 at-bats, while since then he’s given up just six walks in 59 at-bats, even though he’s been throwing it out of the zone more. Right-handers are simply swinging at it more and putting it in play more and more often. And despite throwing out of the zone more, he’s getting hurt in the zone more often. Maybe the pitches he’s making in the zone are really hittable. Maybe I’m grasping at straws and it’s all randomness. wOBAA has been up and down (and is still really high), so it’s hard to tell if anything he’s doing is making a difference. He is tinkering with the sinker and getting more ground balls, so it’s just a matter of limiting the damage on hits that aren’t ground balls.

Since he dialed back his sinker, he’s been relying more on his four-seamer. This is promising because in terms of wOBAA it’s been his most effective pitch against right-handers next to the curveball (which I’ll get to soon). He’s throwing his four-seamer the fastest he has in his career and it’s missing a lot more bats. As long as he keeps it up, he will hopefully trend in the right direction.

But I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Robbie’s most interesting pitch: his slider-thing. Okay, it’s a slider, and it’s probably more conventional than I’ve convinced myself while writing this. Take a look:

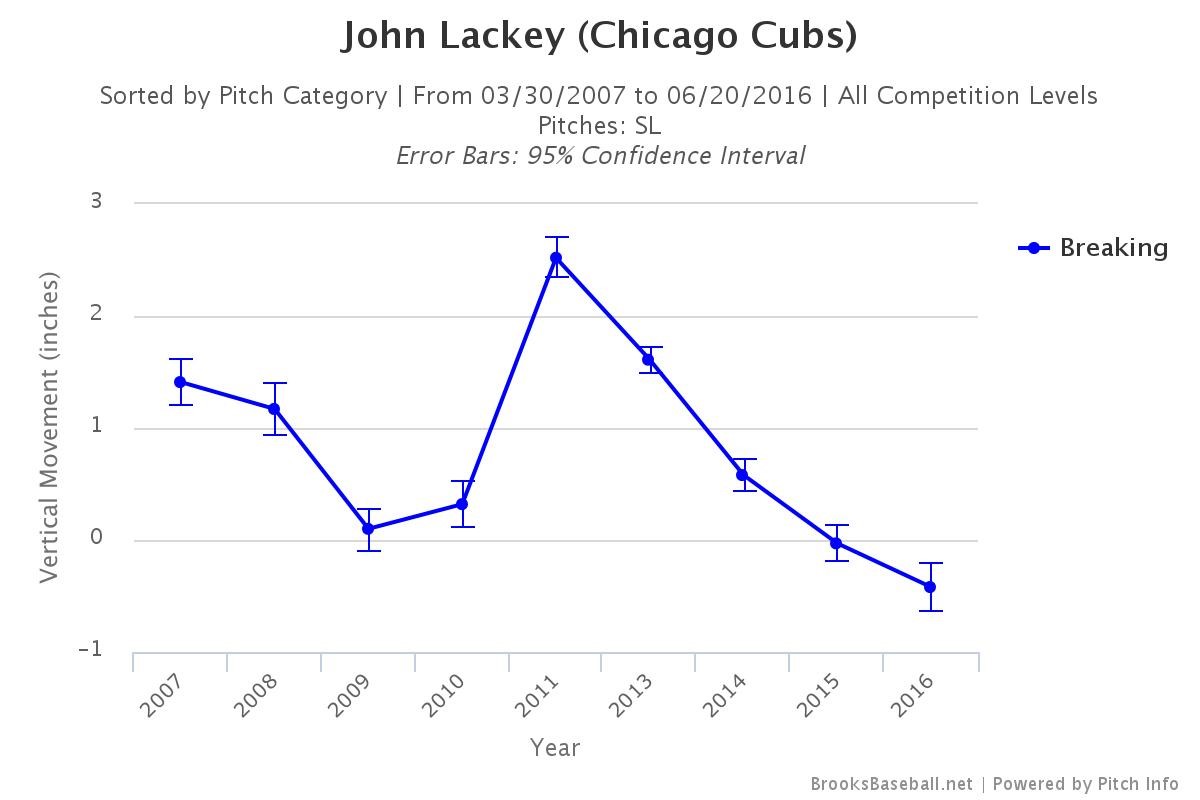

It has primarily 12-6 movement, and it’s only added more movement since last year:

| Slider Movement |

|

Horizontal Movement (in.) |

Vertical Movement (in.) |

| 2015 |

1.42 |

1.71 |

| 2016 |

1.88 |

2.96 |

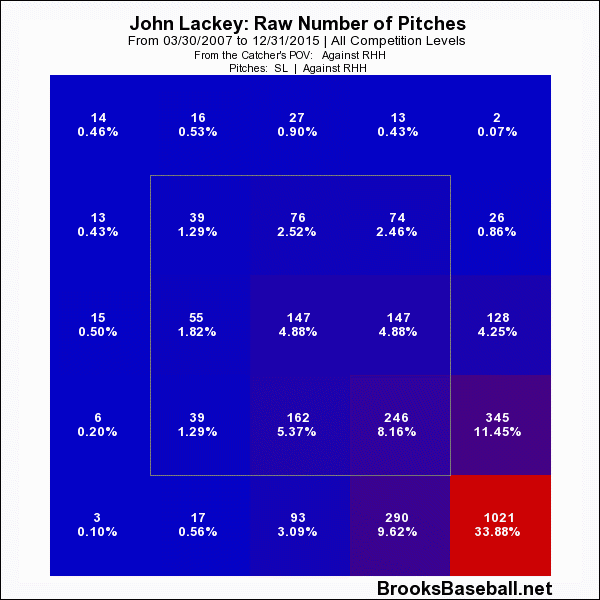

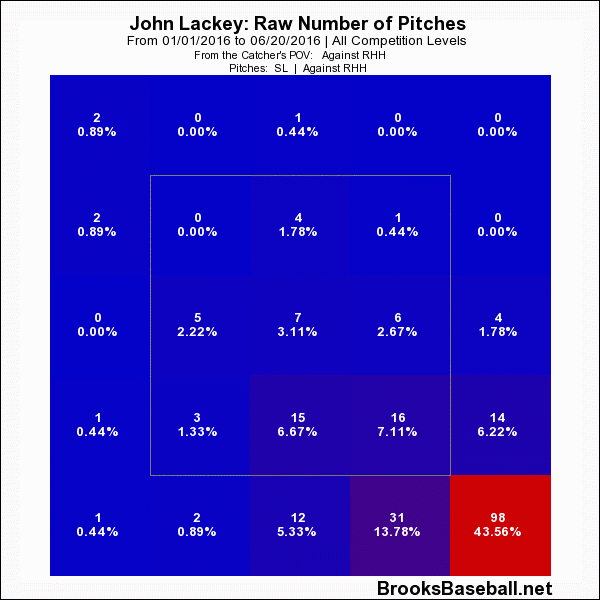

He mostly throws it to lefties, but he’s thrown it 12% of the time to right-handers, so it’s worth examining. He’s also been throwing it more since he ditched the changeup. Righties have a 0.312 wOBA against it, which isn’t spectacular, but it’s a modest improvement from the .352 mark last year. But the most striking thing about his slider is that right-handers are hitting it on the ground 58% of the time! That’s an 18-point improvement from 2015.

His uptick in grounders on the slider could be due to a number of things. As I noted, he’s throwing it faster. About 2 MPH faster, and it sits in the 85 MPH range on average. He likes to spot it low and inside just off the corner of the zone to righties, and he seems to be hitting that location a bit better now. But what jumps out most to me is that while he’s throwing it for strikes less, righties are swinging at it at the same rate, so it stands to reason that they’re making worse contact. Most of the damage appears to come when it’s in the zone and up. When they do hit it in the air (fly balls and line drives), they hit it out 11% of the time. On average, he threw the slider more in June than in April or May and he’s getting fewer fly balls on it than he did in May, so it appears to be trending in the right direction. And if you remember the chart above, he has lowered the HR/(FB+LD) rate since last season. So if he can keep it down, the slider should be a very effective weapon against righties.

One last thing I’ve been avoiding: the curveball. Brooks Baseball says he’s throwing one, while here at FanGraphs it’s lumped in with the slider. It could be just a misclassified wonky slider. He’s only thrown it 61 times this year, so it’s hard to know what to make of it, but see for yourself. Here it is catching Hunter Pence looking:

And here’s a slider for reference (on the very next pitch mind you):

The two have similar sliding action, it’s just that the top one looks more curve-y. It’s a little hard to me to tell the difference by looking at them (though the movement profiles at Brooks are a little different). It looks like he may have a higher release point on the second pitch, which would be consistent with a curve. At Brooks his release point for the curveball is a little higher, albeit not by much. It’s a trend worth keeping an eye on.

If he really has added a curveball to his repertoire for good, the results look promising. So far, he’s gotten almost 50% whiffs per swing, a 58% ground ball rate, and hasn’t allowed a single right-hander to reach on it (and only one lefty). That’s just 10 at-bats, but five of those resulted in strikeouts. Again, it’s a small sample size, but if these results continue, he may have found his pitch to beat the platoon split.

Bottom line, Robbie Ray has been far worse against right-handed hitters this year because of his sinker and changeup. He’s ditched his changeup, which is probably for the best. His sinker has been a mixed bag, but he is getting more ground balls. What’s more, he’s been throwing his four-seamer — his best pitch — a lot more often, and he’s been getting tons of ground balls. If he sticks to the fastball and keeps the slider down, he shouldn’t get torched by righties like he has. And he may even be developing an effective curveball to get them out.

Against lefties, it’s a little simpler. He’s doing largely the same things, just missing more bats and striking out more guys. It’s hard to say with such a small sample size, but it’s a reason for optimism.

In 2016, Robbie Ray has been better, but also worse. However, recently he’s shown some good signs that could make him better, and also better.

Certain stats and tables courtesy of Brooks Baseball. Gifs from Baseball Savant and Inside the ‘Zona.