Knuckleballer R.A. Dickey set record marks for a starting pitcher in the 21st century in terms of breaking ball percentage, usually hovering around 50%. The most prominent other examples are:

Which Starters Have Thrown the Most Breaking Stuff?

But Clayton Kershaw could do something unprecedented this season. It may still be early, this goes beyond simply what happened during this first few weeks of baseball.

It’s well-documented that the future Hall of Famer doesn’t have the same zip on that fastball that he used to, which was most concerning during the 2019 season where the heater topped out at 90.3 mph. Giving up a lead to the Nats in Game 5 on back-to-back homers before being knocked out of the NLDS might have been the catalyst for a change in approach during the following offseason, but that’s just pure speculation on my part.

Kershaw went to Driveline, and through a meticulous study of his mechanics was able to make some minor adjustments and give himself a bit of velocity back. For a pitcher into his thirties, that’s especially huge.

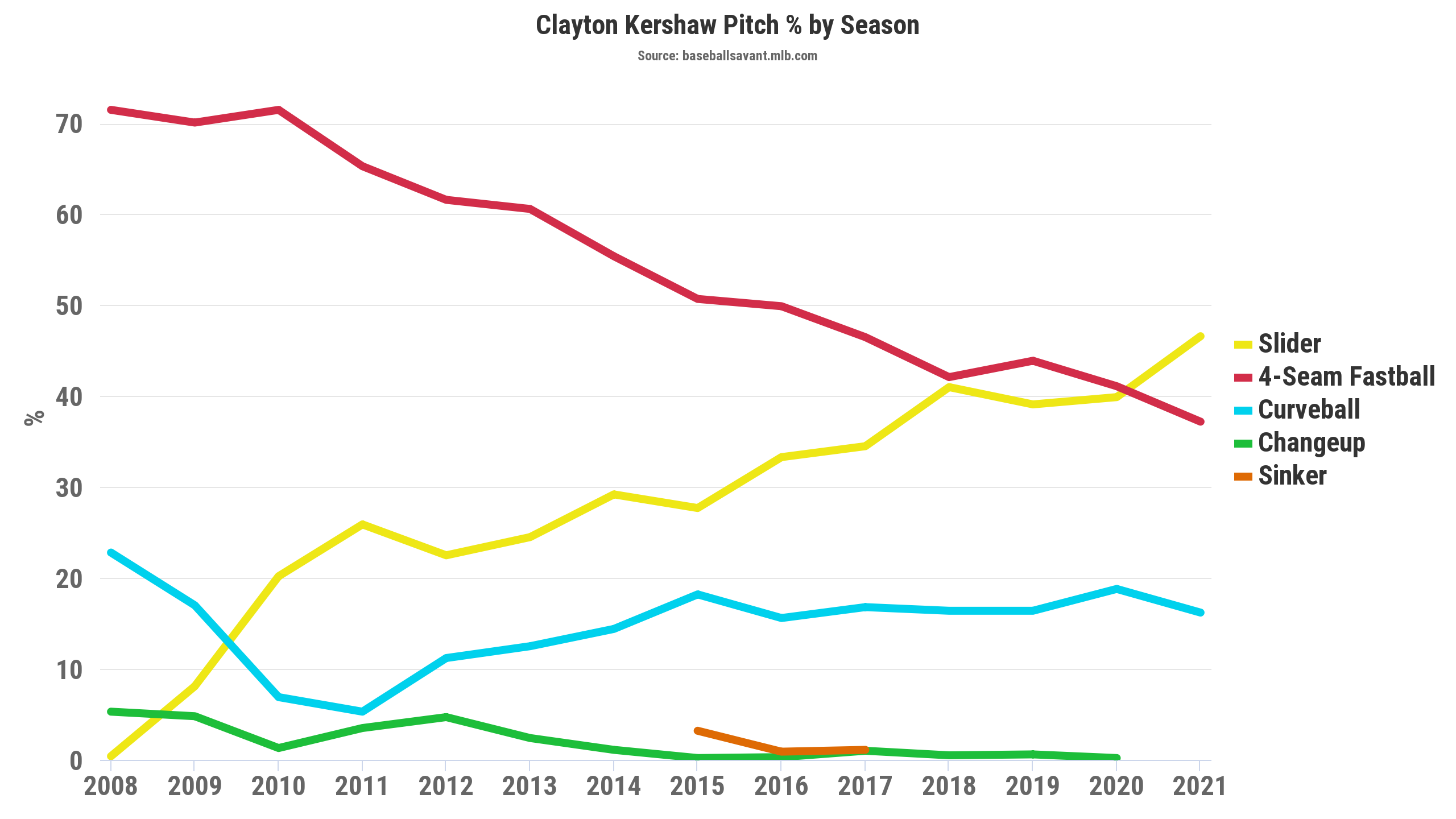

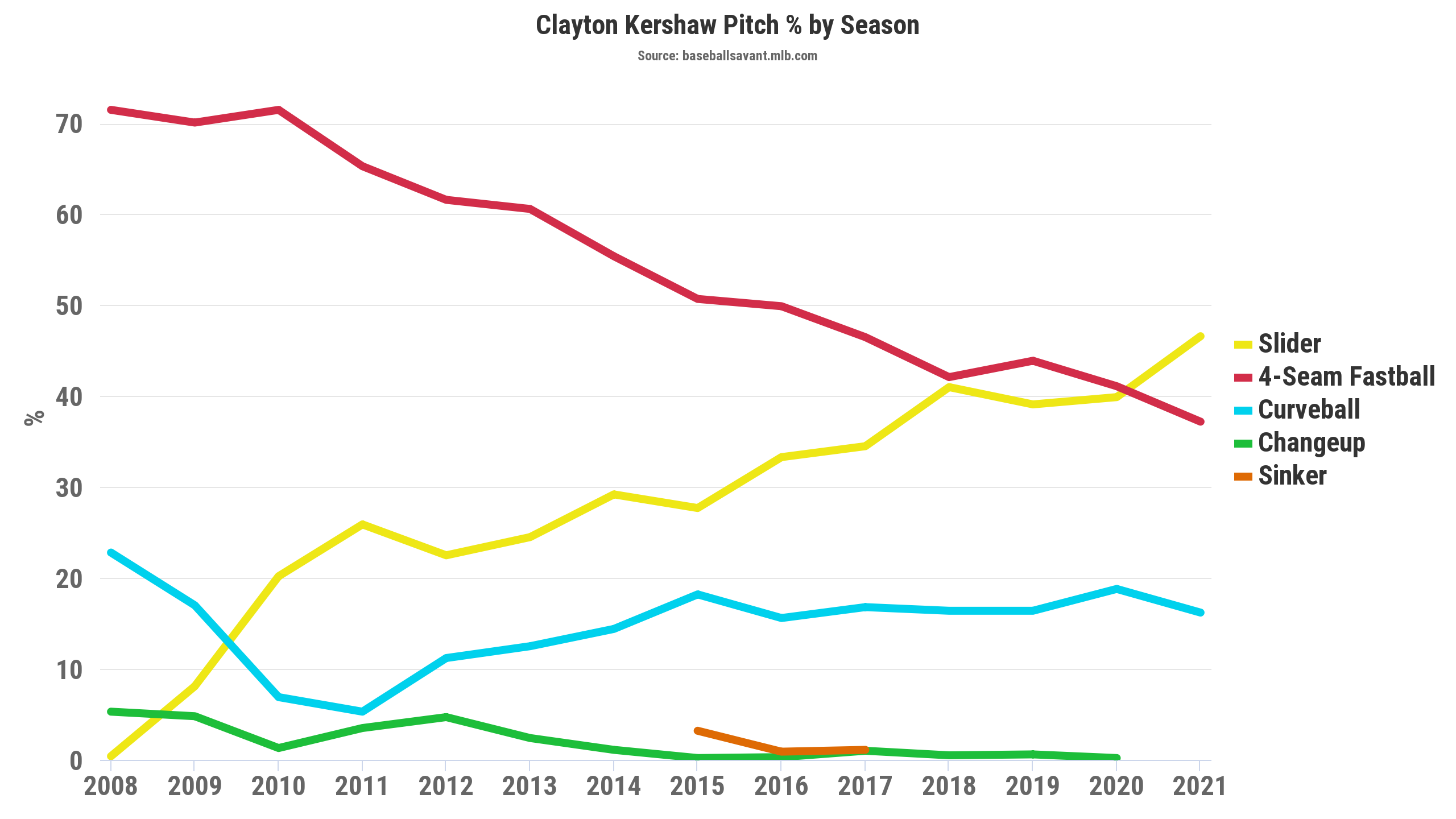

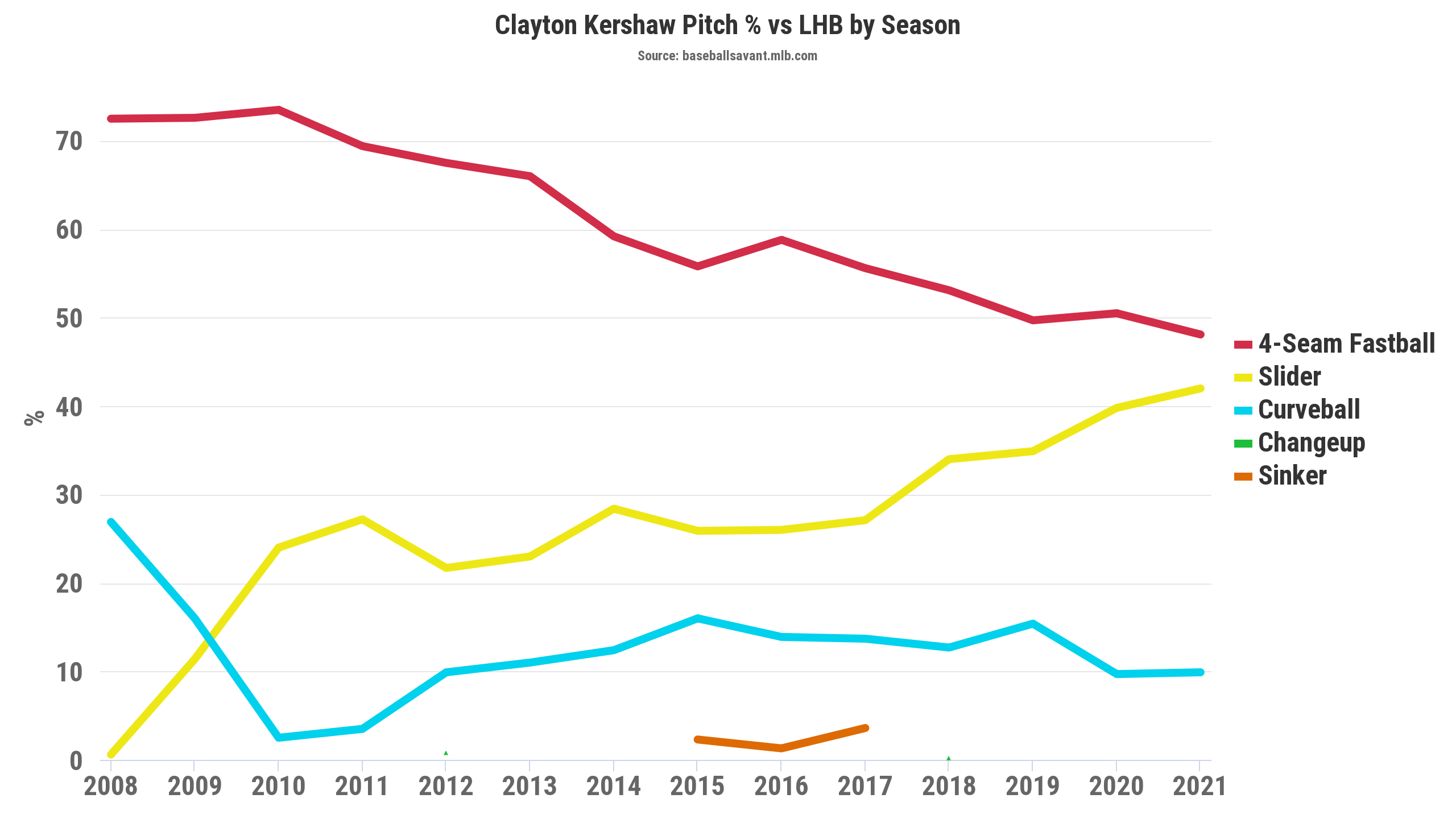

One could look to that moment and mark it as a turning point, but to discuss Kershaw’s pitch selection, we must recognize that since the development of his slider way back when in a bullpen section in Wrigley Field (and even more so since his first Cy Young campaign in 2011), the left-hander has been steadily increasing the slider’s usage to the same rate he was decreasing the fastball selection. Just take a look at the graphic.

We are four starts into Kershaw’s 2021 season, and so far he’s maintained a steady pace towards the first season of a breaking ball rate of 60% or above.

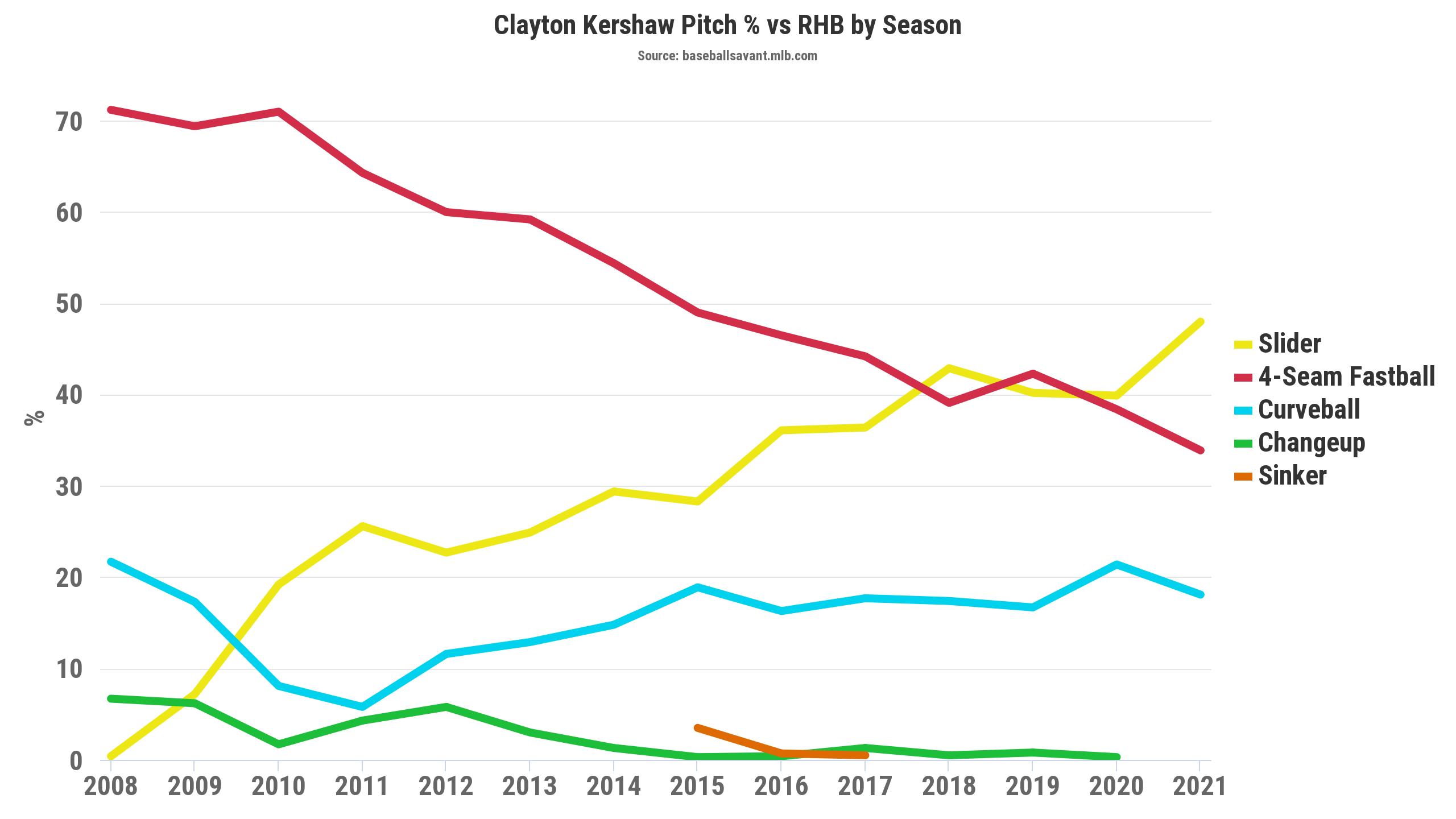

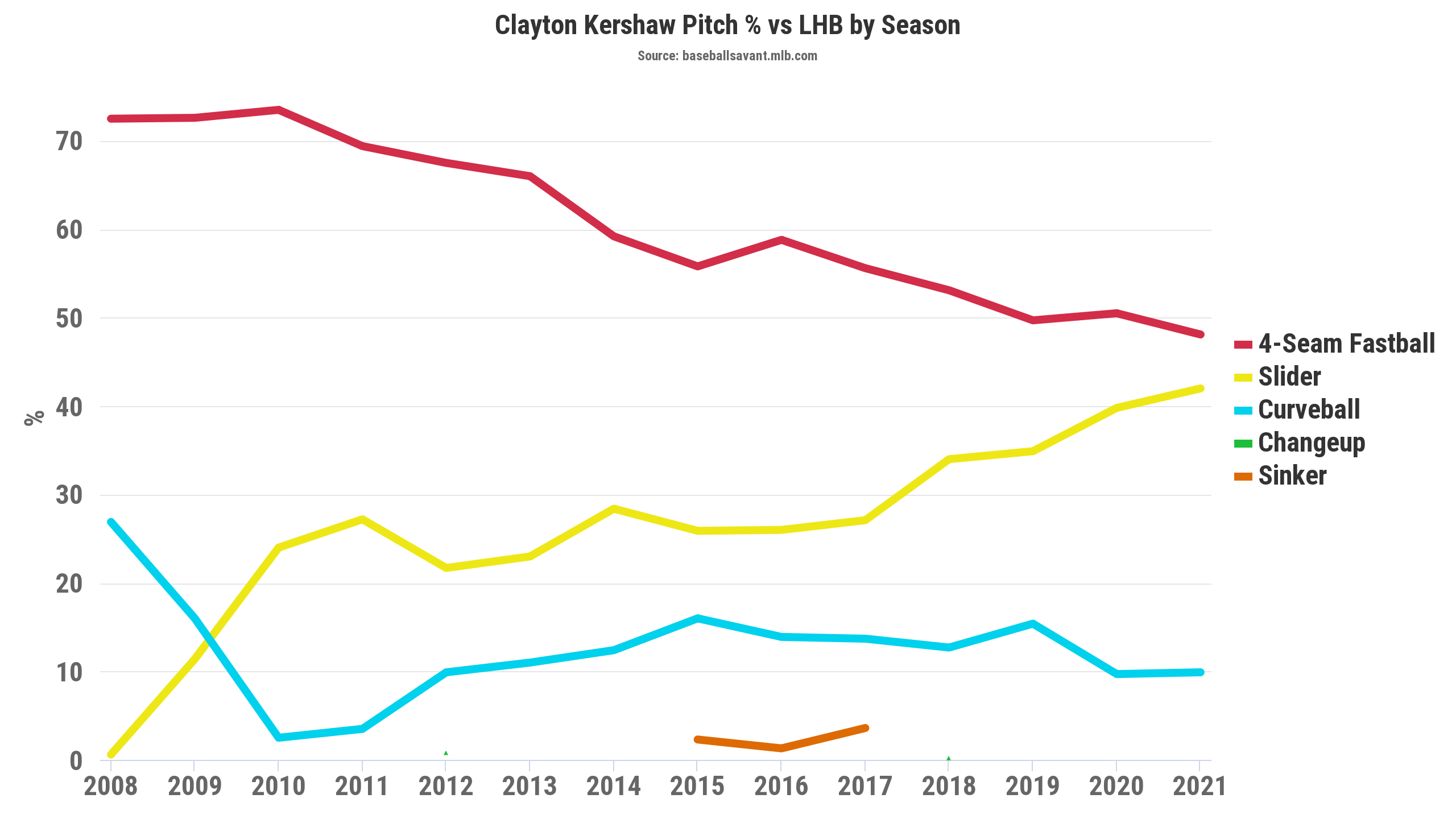

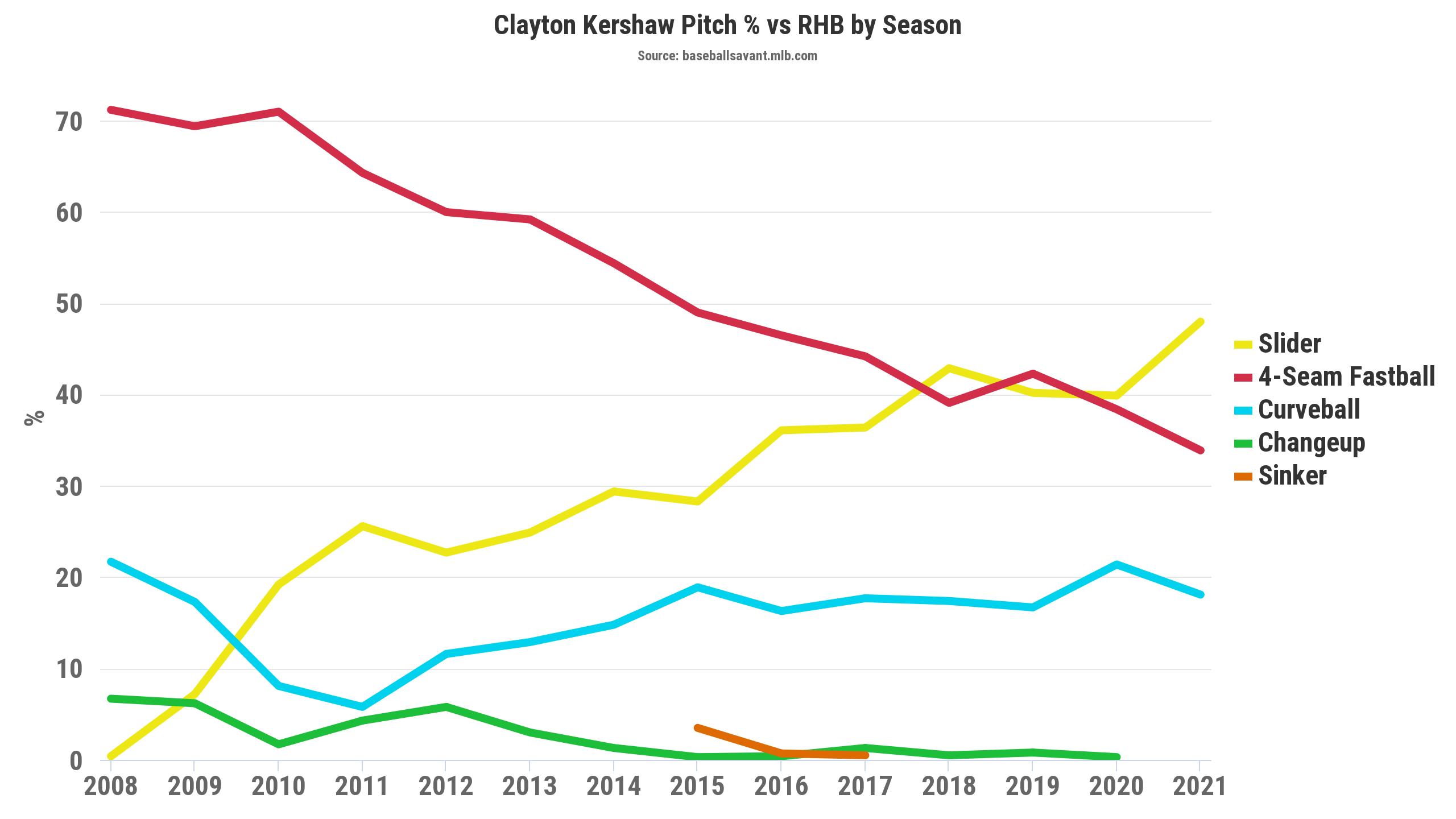

The bulk of this change comes from Kershaw’s significant increase of sliders, specifically against right-handed hitters.

As you can see, he went from the low 40s in slider percentage (40.2 and 39.8 in 2019 and 2020, respectively) to 48 over his first four starts. I know it’s early, but if you are a right-handed batter against Kershaw in 2021, you’re basically getting three fastballs out of 10 pitches. The sample size against left-handed batters is small, just a total of 81 pitches, but it follows his career trend with a not-so-accentuated increase in breaking ball usage.

Here is a table of his pitch usage during each game this season:

Clayton Kershaw’s First Four 2021 Starts

| Pitch Usage |

@ Rockies |

@ Athletics |

vs. Nationals |

@ Padres |

| Fastballs: |

28 (36%) |

34 (37%) |

30 (35%) |

39 (40%) |

| Sliders: |

35 (45%) |

44 (48%) |

41 (48%) |

44 (45%) |

| Curveballs: |

14 (18%) |

13 (14%) |

15 (17%) |

15 (15%) |

| Breaking%: |

63% |

62% |

65% |

60% |

It’s about as close to the same approach as you can get in terms of pitch selection. As the first graphic showed, somewhere around the 2018 season Kershaw began throwing the slider just as much as he threw the fastball, and this could be the year he takes it one step forward. After all, he looked pretty good striking out Fernando Tatis Jr. three times with the same pitch just one night after Tatis hit a bomb against Walker Buehler in his return from the IL.

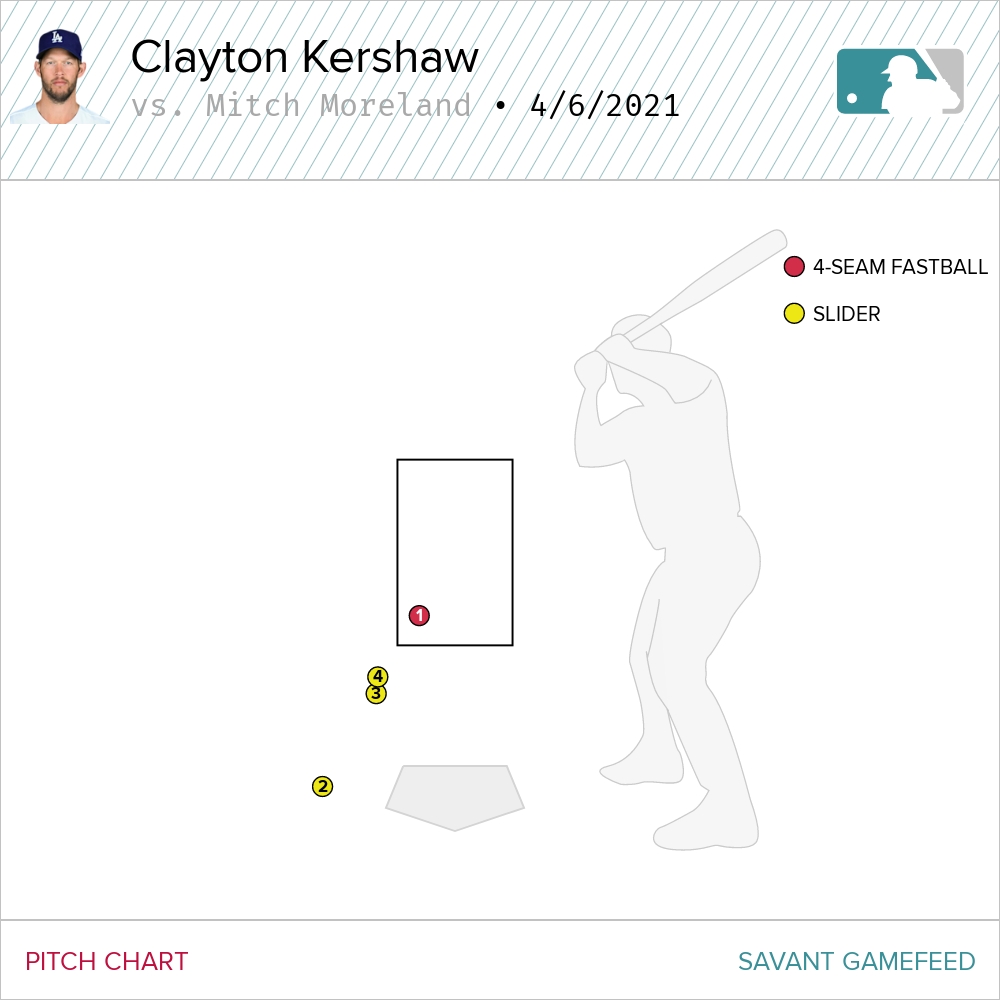

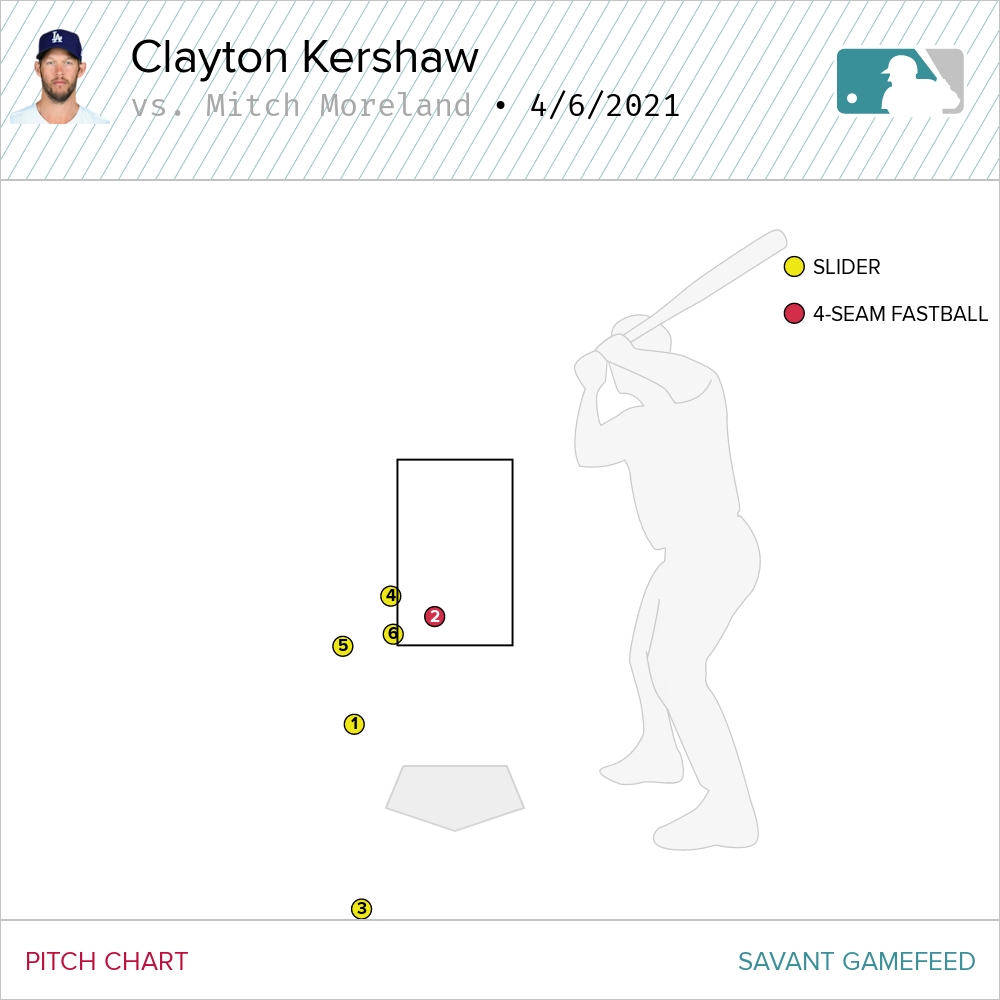

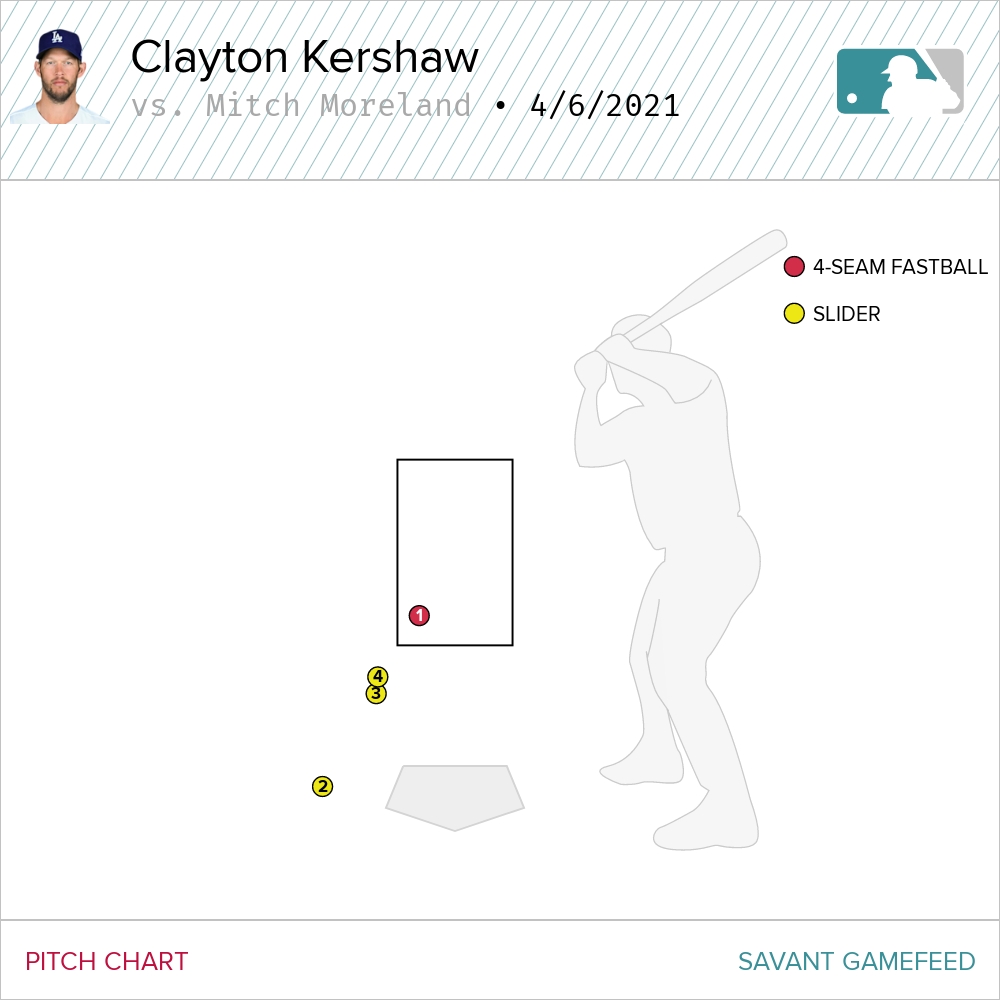

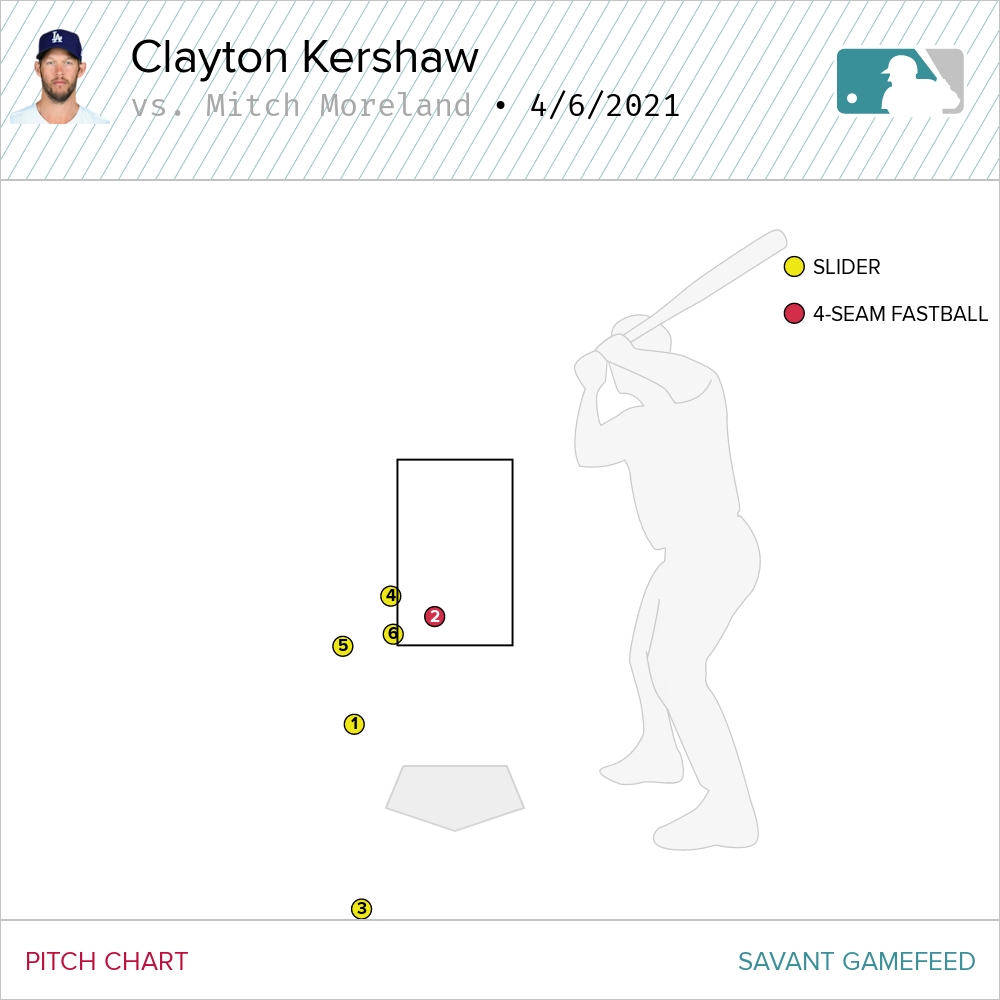

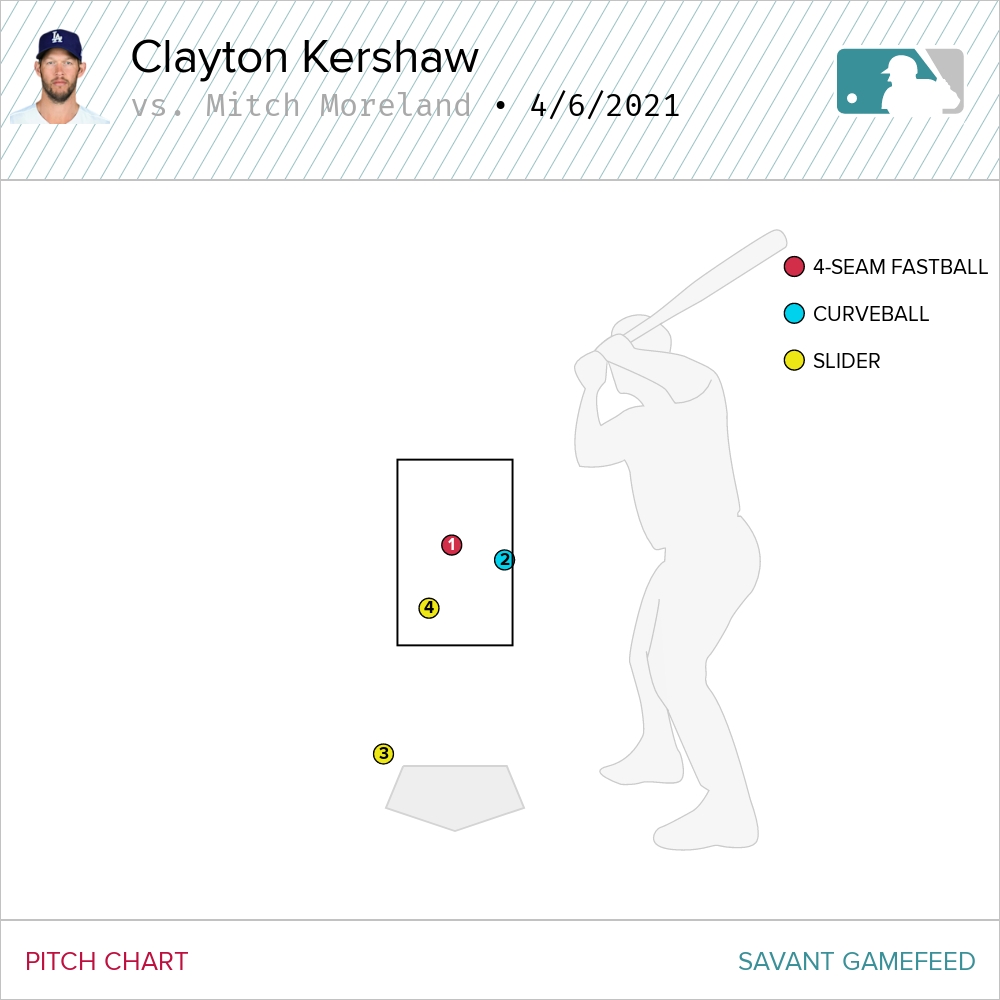

What also helps the left-hander throw that slider so often is the variations of it. Just ask Mitch Moreland.

The first slider Kershaw threw him here went for a ball with a horizontal break of three inches, but Moreland would strike out swinging (on a slider) as the next two broke eight and seven inches, respectively.

The second time up, Moreland saw six pitches and five were sliders, including the last one to punch him out, which had 30 inches of vertical break and five horizontal.

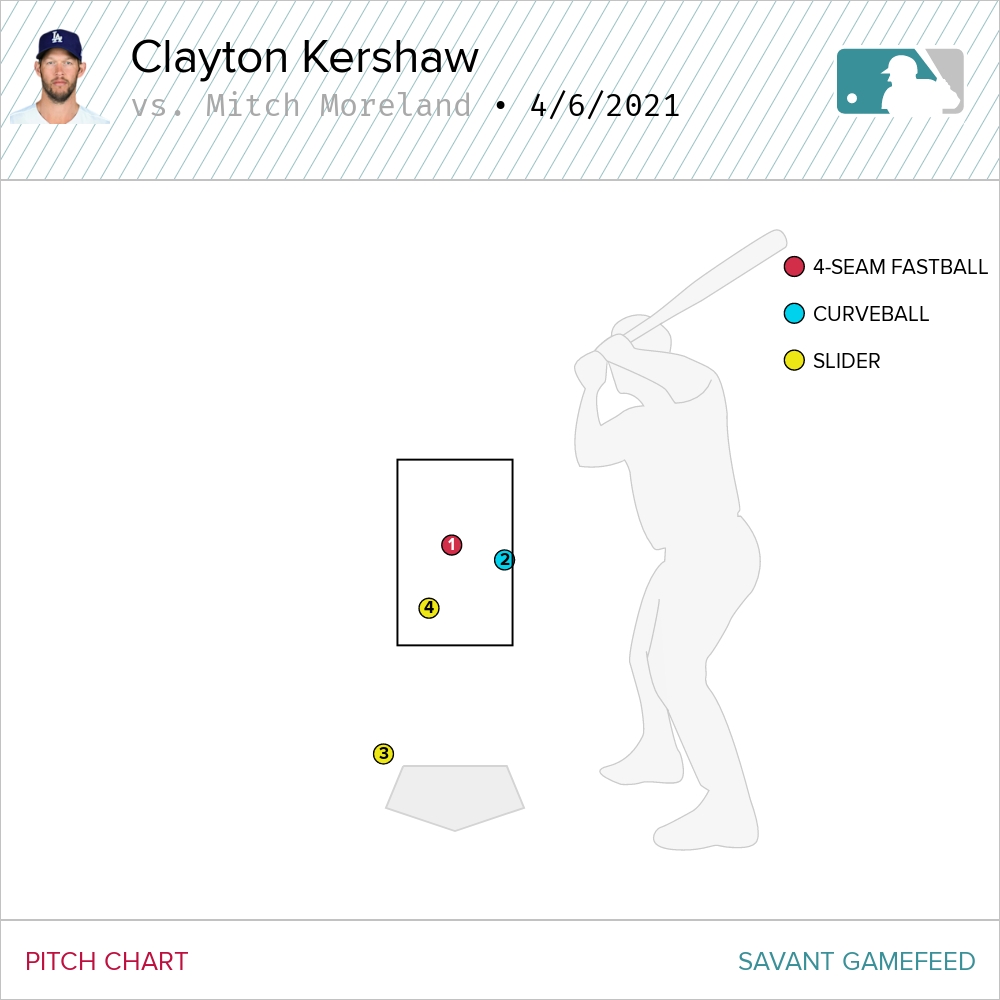

Third time’s the charm? Not so much. Kershaw threw another couple of sliders to finish Moreland off, the first for a ball with a vertical break of 24 inches, but the second one had 30, resulting in a weak grounder to the first baseman.

We’ll see what the season delivers, but so far Kershaw has looked really good following the career trend of pitching selection that’s been a constant since 2011. How far will he go in terms of breaking ball usage? My guess is we’ve seen the limit, or roughly that, for the foreseeable future. It remains to be seen if he can sustain it at that level moving forward, but whether that 60% mark is reached or not, it’s almost a given that he’ll set a career high and also perhaps the new record for non-knuckleballers, his only obstacle being this new “cutterless” Shane Bieber, although I’m betting he’ll bring it back at some point.

Note: No homers over the first four starts is an encouraging sign for Kershaw, and if he experiences a decrease in a trend that was working against him, let’s just say the rumors of his demise might’ve been a little exaggerated. He could may no longer be the overwhelming best pitcher in the game, but he can certainly still be a bona fide ace.

Estevão Maximo is an aspiring sportswriter from Brazil. You can find more of his writing here and here.