Newcomers Find Their Way at Home

The Boston Red Sox have been tightly related with highly-touted prospects during the past months and even years. Taking a quick look at MLB.com’s Top 100 Prospects rankings from 2015 to 2017, we find two names come up fairly consistently. Those belong to infielders Yoan Moncada and Rafael Devers. The former entered the 2015 ranks as “the best teenage prospect to come out of Cuba since Jorge Soler in 2011” and signed with Boston for $31.5 million, which smashed the biggest amount to date registered by the Reds’ signing of Aroldis Chapman for $16.25 million. While Devers’ price ($1.5 million) was nothing close to Moncada’s, he was also praised as “the best left-handed bat on the 2013 international market.”

Multiple names from the 2015 class of prospects have already seen large major-league play time (Byron Buxton, Corey Seager, Joey Gallo and Aaron Judge), and the time has come for Moncada and Devers to start writing their full-time MLB stories. In the case of Moncada, Boston opted to trade him to the White Sox for Chris Sale during the past off-season while keeping Devers in town. Anyway, and as things have turned out, both have practically debuted in parallel during this season for their franchises, being called up for quite different reasons. In the midst of a complete rebuild, Chicago will count on Moncada to take on the third-base position from now on. Boston, on the other hand, wanted to improve their infield a hair and seem to have opted for Devers as an in-house solution to their woes.

As the date of the writing of this article, this is, Tuesday, July 25 (better known as National Rafael Devers’ Day given his major-league debut with the Red Sox), Moncada will have the chance to play as much as 65 games and Devers 60. They will probably not reach those numbers — at least not Devers, knowing Boston’s contender status and probable use of platoon hitters during the rest of the season. Another fact of interest is that Yoan Moncada is 22 years old and Rafael Devers is just 20. So, those numbers will make for a baseline on what to look for during the rest of this article, which will focus on how call-ups perform in their debut seasons, both home and away.

Prospects made huge jumps just going from the minors to the majors, change cities and clubhouses, meet new teammates, and much more, but you would guess that after settling in they’d produce more at home than far away from it. In order to actually know if this holds true, I ran a set of queries on Baseball-Reference.com to find out. I’ll be looking at rookie-season splits from 2000 to 2017 in which the players debuting were between 20 and 22 years of age (such as those of Moncada and Devers). A total of 87 players within those parameters have seen major-league action during the selected time span. So we’ll be working with 174 home/away splits in order to know if rookies of ages 20-22 have historically played better at home or away from it as we may expect.

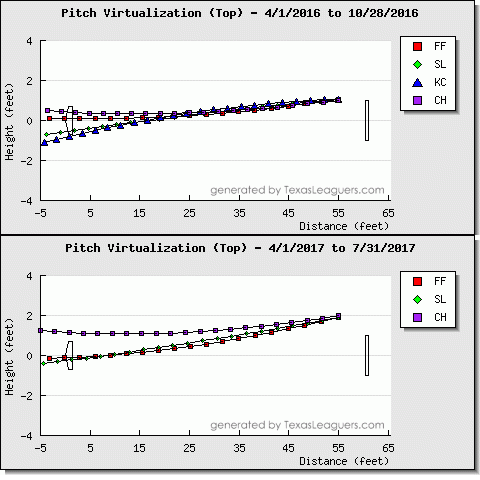

First of all, I’ve looked at “playing time” stats, this is: games, games as a starter and plate appearances. As much as we could expect players to perform better at home than away over their first few games, we could expect teams to “protect” their rookies and deploy them more frequently at home than on the road. As it turns out, though, the statistics for the home and away splits are virtually the same for the three mentioned categories. First myth debunked.

Moving on to what really matters, production, we can try and see how well players have hit in their ballparks compared to other venues, and whether there are or not big differences in this aspect.

Subtle differences start to appear between the games played at home and those played away in terms of runs scored and hitting. There are no big differences between the splits, surely, but it seems that home performances have edged away ones by a hair during the past 17 years on average. The biggest different in any of the studied statistics comes in both the doubles and home-run categories at 0.3 points each in favour of the home split.

Another interesting set of statistics to look at are those related with base-stealing. By logic, players would be expected to feel more comfortable, confident and willing to steal bases at home rather than in other parks. Again, that preconception seems to be wrong. Between the 87 players studied, the average of steal attempts was higher away than at home, and even the success was five points higher when stealing in other ballparks rather than in their own one.

Finally, we must turn our attention to the game of percentages and look at the slash line of the analyzed players in terms of BA, OBP and SLG. On top of that, I included the average tOPS+ and sOPS+ values. The former of those last two is meant to represent the player’s OPS in the split relative to that player’s total OPS during the full season (not accounting for the home/away split), with a value greater than 100 indicating that he did better than usual in the split. The second one is the OPS in the split relative to the league’s split OPS (again, a value greater than 100 indicates the player did better than the league in this split).

And here is where our home/away splits, once for all, truly separate themselves. Not one, not two, not three, but every percentage value posted at home by the average 20-to-22 year-old rookie from 2000 to 2017 has been better than the number registered far from it, and not by little. The difference in BA is of 15 points, in OBP of 23, in SLG of 23, in tOPS+ of 13 and in sOPS+ of 4. That yields an average difference of 20.3 points in the slash line and of 8.5 in the OPS+ metrics, which is huge. It is interesting to see how the average rookie performance is under the league-average level (under 100 sOPS+) both at home and away, but how said average was able to put up much better numbers at home (106 tOPS+) than away (93 tOPS+).

Just in case the rest of the data didn’t make it clear, which it actually didn’t, this leaves no doubt or case for equity open. After all, rookies probably prefer to play at home, sweet home.

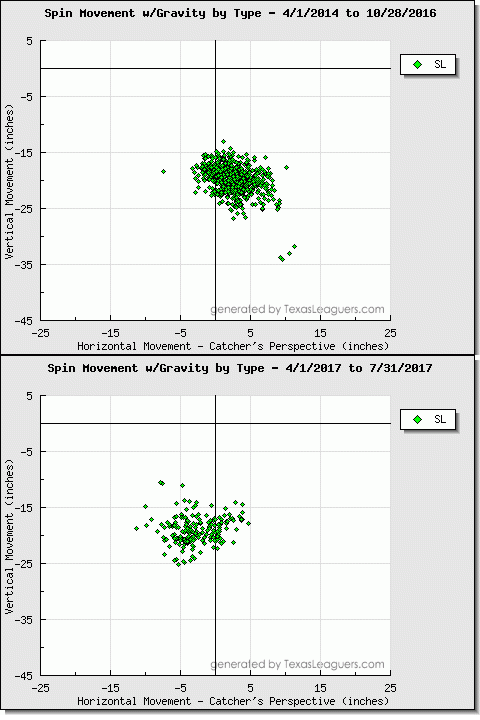

But now that we know that newcomers not older than 22 years when they play their first major-league games tend to perform better at home, it is just a thing of curiosity to explore some of the unique cases that have occurred during the past 17 seasons to the 88 players of our study. We have been looking at the average rookie during the past few paragraphs, but as expected, each case is unique in itself and would make for a complete study on its own. Next is a table containing the rookies with a 45+ point differential in tOPS+ (with at least 60 games played), so we can measure how different their production was at home and on the road. Players are ordered by the absolute difference, with negative values meaning their production away was better than that at their home ballpark.

As it turns out, only 16 of 72 players had differences of 45+ points in tOPS+ between their games at home and those played away. Of those 16, though, seven were better far from their team’s stadium, something not really expected, much less in the case of Stanton and his minus-94 differential.

Just for fun, let’s look at Giancarlo’s case, whose split numbers are radically different while having played almost the same amount of games home and away during his rookie season. In 180 PA at home he hit 29 balls, including 7 home runs, for a BA/OBP/SLG line of .182/.272/.599 and 52 total bases. In 216 PA away he hit 64 balls with 15 home runs, posting a .320/.370/1.020 slash line and getting 130 total bases. What could be seen as a terrible entry year by looking at just the production at home (league-relative sOPS+ of 60) turns into a monster season while considering what Stanton was able to do outside of Miami (183 sOPS+). Something similar happened to Jay Bruce, Logan Morrison or more recently Miguel Sano, only in opposite venues.

As a final note, it can also be seen how only six of the 16 players in the table above had a big differential while debuting prior to 2010. The other 10 players made their debuts from 2010 on, which could mean that the trend is for rookies to have much more variable productions in different venues that the average historical newcomer.

We still don’t know how Moncada and Devers will perform during the rest of the season, but if that last supposition holds true, then White Sox and Red Sox fans just can hope for their players to at least do more damage at home than away, so they get to watch their jewels explode in front of their own eyes instead of between different ballparks around the nation.