Examining the foundations of batting analysis began in Part 1 with an historical examination of the earliest statistics designed to examine the performance of batters. In Part 2, I presented a new method for calculating basic averages reflecting the “real and indisputable” rate at which batters reached base. In Part 3, I examined the development of run estimation techniques over the last century, culminating with the linear weights system. I will employ that system now as I reconstruct run estimation from the bottom up.

We use statistics in baseball to tell stories. Statistics describe the action of the game or the performance of players over a period of time. Statistics inform us of how much value a player provided or how much skill a player showed in comparison to other players. To tell such stories successfully, we must understand how the statistics we use are constructed and what they actually represent.

A single, for instance, seems simple enough at first glance. However, there are details in its definition that we sometimes gloss over. In general, a single is any event in which the batter puts the ball into play without causing an out, while showing an accepted form of batting effectiveness (reaching on a hit), and ultimately advancing to first base due to the primary action of the event (before any secondary fielding errors or advancement on throws to other bases). Though this is specific in many regards, it is still quite a broad definition for a batting event. The event could occur in any inning, following any number of outs, and with any number of runners on the bases. The ball could be hit in any direction, with any speed and trajectory, and result in any number of baserunners advancing any number of bases.

These kinds of details form the contextual backdrop that characterizes all batting events. When we construct a statistic to evaluate these events, we choose what level of contextual detail we want to consider. These choices define our analysis and are critical in developing the story we want to tell. For instance, most statistics built to measure batting effectiveness—from the simple counting statistics like hits and walks, to advanced run estimators like Batter Runs or weighted On Base Average (wOBA)—are constructed to be independent of the “situational context” in which the events occur. That is, it doesn’t matter when during the game a hit is made or if there are any outs or any runners on the bases at the time it happens. As George Lindsey noted in 1963, “the measure of the batting effectiveness of an individual should not depend on the situations that faced him when he came to the plate.”

Situational context is the most commonly cited form of contextual detail. When a statistic is described as “context neutral,” the context being removed is very often the one describing the out/base state before and after the event and the inning in which it occurred. However, there are other contextual details that characterize the circumstances and conditions in which batting events occur that also tend to be removed from consideration when analyzing their value. Historically, where the ball was hit, as well as the speed and trajectory which it took to reach that location, have also not been considered when judging the effectiveness of batters. This has partly been due to the complexity of tracking such things, especially in the century of baseball recordkeeping before the advent of computers. Also, most historical batting analyses focus exclusively on the outcome for the batter, independent of the effect on other baserunners. If the batter hits the ball four feet or 400 feet but still only reaches first base, there is no difference in the personal outcome that he achieved.

If the value of a hit was limited to only how far the batter advances, then there would be no need to consider the “batted-ball context,” but as F.C. Lane observed in 1916, part of the value of making a hit is in the effect on the “runner who may already be upon the bases.” By removing the batted-ball context when considering types of events in which the ball is put into play, we’re assuming that a four-foot single and 400-foot single have the same general effect on other baserunners. For some analyses, this level of contextual detail describing an event may be irrelevant or insignificant, but for others—particularly when estimating run production—such a level of detail is paramount.

Let’s employ the linear weights method for estimating run production, but allow the estimation to vary from one completely independent of any contextual detail to one as detailed as we can make it. In this way, we’ll be able to observe how various details impact our valuation of events. Also, in situations where we are only given a limited amount of information about batting events, it will allow us to make cursory estimations of how much they caused their team’s run expectancy to change.

To begin, let’s define the run-scoring environment for 2013.[i] While we have focused on context concerning how events transpired on the field, the run scoring environment is another kind of contextual detail that characterizes how we evaluate those events. The exact same event in 2013 may not have caused the same change in run expectancy as it would have in 2000 when runs were scored at a different rate. We will define the run scoring environment for 2013 as the average number of runs that scored in an inning following a plate appearance in each of the 24 out/base states – a 2013-specific form of George Lindsey’s run expectancy matrix:

| Base State |

0 OUT |

1 OUT |

2 OUT |

| 0 |

0.47 |

0.24 |

0.09 |

| 1 |

0.82 |

0.50 |

0.21 |

| 2 |

1.09 |

0.62 |

0.30 |

| 3 |

1.30 |

0.92 |

0.34 |

| 1-2 |

1.39 |

0.84 |

0.41 |

| 1-3 |

1.80 |

1.11 |

0.46 |

| 2-3 |

2.00 |

1.39 |

0.56 |

| 1-2-3 |

2.21 |

1.57 |

0.71 |

While we will focus on examining various levels of contextual detail concerning the events themselves, the run-scoring environment can also be varied based on contextual details concerning the scoring of runs. The matrix we will employ, as defined by Lindsey, reflects the average number of runs scored across the entire league. If we wanted, we could differentiate environments by league or park, among other things, to try and reflect a more specific estimate of the number of runs produced. As the work I’m going to present is meant to provide a general framework for run estimation, and these adjustments are not trivial, I’m going to stick with the basic model provided by Lindsey.

With Lindsey’s tool, we can define a pair of statistics for general analysis of run production. Expected Runs (xR) reflect the estimated change in a team’s run expectancy caused by a batter’s plate appearances independent of the situational context in which they occur. A batter’s expected Run Average (xRA) is the rate per plate appearance at which he produces xR.

xRA = Expected Runs / Plate Appearances = xR / PA

xR and xRA create a framework for estimating situation-neutral run production. Based on the contextual specificity that is used to describe the action of a plate appearance, xR and xRA will yield various estimations. The base case for calculating expected runs, xR0, is calculated independently of any contextual detail, considering only that a plate appearance occurred. By definition, an average plate appearance will cause no change in a team’s run expectancy. Consequently, no matter a player’s total number of plate appearances, his xR0 and, by extension, his xRA0, will be 0.0.

This is completely uninformative of course, as base cases often are. So let’s add our first layer of contextual specificity by noting whether an out occurred due to the action of the plate appearance. This is the most significant contextual detail that we consider when evaluating batting events – it is the only factor that determines whether a plate appearance increases or decreases a team’s run expectancy. In 2013, 67.5 percent of all plate appearances resulted in at least one out occurring. On average, those events caused a team’s run expectancy to decrease by .252 runs. The 32.5 percent of plate appearances in which an out did not occur caused a team’s run expectancy to increase by .524 runs on average. We’ll define xR1 as the estimated change in run expectancy based exclusively on whether the batter reached base without causing an out; xRA1 is the rate at which a batter produced xR1 per plate appearance.

You’ll notice that the components that construct xRA1 can only take on two values—.524 and -.252—in the same way that the components that construct effective On Base Average (eOBA) (as defined in Part 2) can only take on two values—1 and 0. These statistics—xRA1 and eOBA—have a direct linear correlation:

In effect, xRA1 is a weighted version of eOBA, incorporating the same contextual details but on a different scale. This estimation provides us with an association between reaching base safely and producing runs. However, the lack of detail would suggest that all players that reach base at the same rate produce the same value, which is over simplified. It’s why you wouldn’t just use eOBA, or eBA, or any other basic statistic that reflects the rate which a batter reaches base, when judging the performance of a batter. Let’s add another layer of contextual detail to account for the different kinds of value a batter provides when he reaches base.

xR2 will represent the estimated change in run expectancy based on whether the batter safely reached base and the number of bases to which he advanced due to the action of the plate appearance; xRA2 will be the rate at which a batter produces xR2 per plate appearance. While xR1 and xRA1 were built with just two components to estimate run production, xR2 and xRA2 require five components: one to define the value of an out, and four to define the value of safely reaching each base.

In 2013, a batter safely reaching first base during a plate appearance caused an average increase of .389 runs to his team’s run expectancy. Reaching second base was worth .748 runs, third base was worth 1.026 runs, and reaching home was worth 1.377 runs on average. Where xRA1 provided a run estimation analog to eOBA, xRA2 is built with very similar components to effective Total Bases Average (eTBA), though it’s not quite a direct linear correlation:

The reason xRA2 and eTBA do not correlate with each other perfectly, like xRA1 and eOBA, is because the way in which a batter advances bases is significant in determining how valuable his plate appearances were. Consider two players that each had two plate appearances: Player A hit a home run and made an out, Player B reached second base twice. Their eTBA would be identical—2.000—as they each reached four bases in two plate appearances. However, from the run values associated with reaching those bases, Player A would record 1.125 xR2 from his home run and out, while Player B would record 1.496 xR2 from the two plate appearances leaving him on second base. Consequently, Player A would have produced a lower xRA2 (.5625) than Player B (.7480), despite their having the same eTBA. These effects tend to average out over a large enough sample of plate appearances, but they will still cause variations in xRA2 among players with the same eTBA.

As stated in Part 2, the two main objectives of batters are to not cause an out and to advance as many bases as possible. If the only value that batters produced came from accomplishing these objectives, then we would be done – xR2 and xRA2 would reflect the perfect estimations of situation-neutral run production. As I hope is clear, though, the value of a batting event is dependent not only on the outcome for the batter but on the impact the event had on all other runners on base at the time it occurred. Different types of events that result in the batter reaching the same base can have different average effects on other baserunners. For instance, a single and a walk both leave the batter on first base, but the former creates the opportunity for baserunners to advance further on average than the latter. To address this, the next layer of contextual detail will bring the official scorer into the fray. xR3 will represent the estimated change in run expectancy produced during a batter’s plate appearance based on:

(1) whether the batter safely reached base,

(2) the number of bases, if any, to which the batter advanced due to the action of the plate appearance, and

(3) the type of event, as defined by the official scorer, that caused him to reach base or cause an out.

xRA3 will, as always, be the rate at which a batter produces xR3 per plate appearance.

Each of the run estimators that were examined in Part 3, from F.C. Lane’s methods through wOBA, are subsets of this level of xR. Expected runs incorporate estimations of the value produced during every event in which the batter was involved, including those which may be considered “unskilled.” The run estimators examined in Part 3 consider only those events that reflected a batter’s “effectiveness,” and either disregard the “ineffective” events or treat them as failures. xR3 provides the total value produced by a batter, independent of the effectiveness he showed while producing it, based solely on how the official scorer defines the events. Consequently, some events, like strikeouts, sacrifice bunts, reaches on catcher’s interference, and failed fielder’s choices, among other more obscure occurrences, are examined independently in xR3. From the two components of xR2 and the five of xR3, we build xR4 with 18 components: five types of outs and 13 types of reaches.

To help illustrate how xR has progressed from level to level, here is a chart reflecting the run values for 2013 as estimated by xR based on the contextual detail provided thus far.

xR Progression

Beyond any consideration of skilled or unskilled production, xR3 is the level at which most run estimators are constructed. It incorporates events that are well defined in the Official Rules of the game, and have been for at least the last few decades, and in some cases for over a century. While we still define most of a batter’s production by his accomplishing these events, we live in an era where we can differentiate between events on the field in more specific ways. Not all singles are identical events. We weaken our estimation of run production if we don’t account for the different kinds of singles, among other events, that can occur. xR3 brought the official scorer into action; xR4 will do the same with the stat stringer.

While the scorer is concerned with the result of an event, a stringer pays attention to the action in between the results. They chart the type, speed, and location of every pitch, and note the batted ball type (bunt, groundball, line drive, flyball, pop up) [ii] and the location to which the ball travels when put into play.While we don’t have this data as far back in time as we have result data, we do have decades worth of information concerning these details. By differentiating events based on these details, we will begin to unravel the “batted-ball context.” Ideally, we would know every detail of the flight of the ball, and use this to group together the most similar possible type of events for comparison.[iii] At present, we’re limited to what the scorers and stringers provide, but that’s still quite a lot of information.

xR4 will represent the estimated change in run expectancy produced during a batter’s plate appearance based on:

(1) whether the batter safely reached base,

(2) the number of bases, if any, to which the batter advanced due to the action of the plate appearance,

(3) the type of event, as defined by the official scorer, that caused him to reach base or make an out,

(4) the type of batted ball, if there was one, as defined by the stat stringer, that resulted from the plate appearance,

(5) the direction in which the ball travelled, and

(6) whether the ball was fielded in the infield or outfield.

xRA4 will be the rate at which a batter produces xR4 per plate appearance.

There are 18 components in xR3 which describe the assorted types of general events a batter can create. When you add in these details concerning the batted-ball context, the number of components increases to 145 for xR4. With such specific details being considered, we can no longer rely on a single season of data to accurately inform us on the average situation in which each type of event occurs; the sample sizes for some events are just too small. To address this, there are two steps required in evaluating events for xR4. The first is to build a large sample of each event to build an accurate picture of their relative frequency in each out/base state. I’ve done this by using a sample covering the previous ten seasons to the one in which the estimations are being made. Once this step is completed, the run-scoring environment in the season being analyzed is applied to these frequencies, in the same way it is when looking at single season frequencies for basic events.

For instance, the single, which is traditionally treated as just one type of event, is broken into 24 parts based on the contextual details listed above. By observing the rate at which each of these 24 variations of singles occurred in each out/base state from 2004 through 2013, and applying the 2013 run-scoring environment, we get the following breakdown for the estimated value of singles in 2013:

| Single |

Left |

Center |

Right |

All |

| Bunt, Infield |

.418 |

.451 |

.436 |

.427 |

| Groundball, Infield |

.358 |

.361 |

.384 |

.363 |

| Pop Up, Infield |

.391 |

.359 |

.398 |

.369 |

| Line Drive, Infield |

.343 |

.369 |

.441 |

.369 |

| Groundball, Outfield |

.463 |

.464 |

.499 |

.474 |

| Pop Up, Outfield |

.483 |

.480 |

.498 |

.488 |

| Line Drive, Outfield |

.444 |

.463 |

.471 |

.460 |

| Flyball, Outfield |

.481 |

.479 |

.490 |

.482 |

This process is repeated for every type of batting event in which the ball is put into play. One of the ways we can use this information is to consider the run value based not on the result of the event, but on the batted-ball context that describes the event. Here are those values in the 2013 run-scoring environment:

|

Popups |

Groundballs |

Fly Balls |

Line Drives |

All Swinging BIP |

| All Outs |

-.261 |

-.257 |

-.226 |

-.257 |

-.249 |

| Infield Out |

-.260 |

-.257 |

——- |

-.297 |

-.260 |

| Outfield Out |

-.269 |

——- |

-.226 |

-.233 |

-.229 |

| Left Out |

-.262 |

-.260 |

-.230 |

-.251 |

-.253 |

| Center Out |

-.262 |

-.281 |

-.223 |

-.257 |

-.257 |

| Right Out |

-.260 |

-.229 |

-.227 |

-.262 |

-.237 |

| All Reaches |

.514 |

.468 |

1.108 |

.571 |

.629 |

| Infield Reach |

.436 |

.381 |

——- |

.390 |

.382 |

| Outfield Reach |

.517 |

.503 |

1.108 |

.572 |

.659 |

| Left Reach |

.516 |

.463 |

1.172 |

.577 |

.632 |

| Center Reach |

.535 |

.443 |

1.006 |

.546 |

.593 |

| Right Reach |

.483 |

.510 |

1.166 |

.593 |

.672 |

| All Infield |

-.257 |

-.199 |

——- |

-.267 |

-.211 |

| All Outfield |

-.003 |

.503 |

.093 |

.402 |

.262 |

| All Left |

-.219 |

-.058 |

.161 |

.332 |

.054 |

| All Center |

-.205 |

-.078 |

.030 |

.312 |

.030 |

| All Right |

-.191 |

-.069 |

.123 |

.326 |

.045 |

| All |

-.207 |

-.068 |

.093 |

.323 |

.042 |

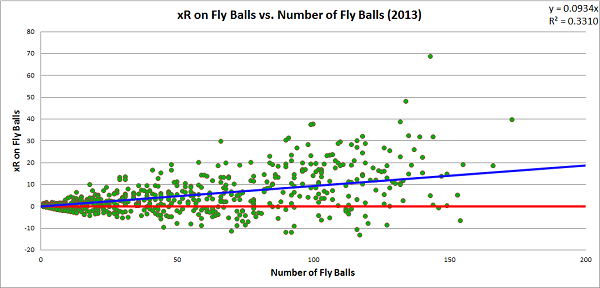

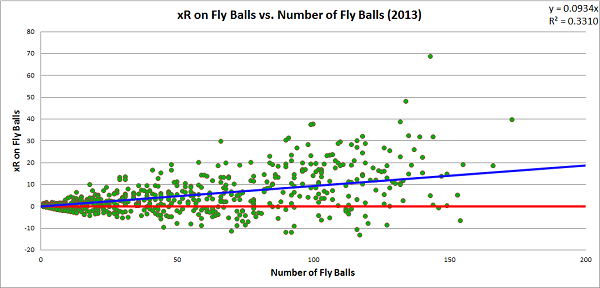

Similarly, we can break down each player’s xR4 by the value produced on each type of batted ball. Here are graphs for xR4 produced on each of the four types of batted balls resulting from a swing, with respect to the number of batted balls of that type hit by the player. For simplicity, from this point on, when I drop the subscript when describing a batter’s expected run total, I’m referring to xR4.

Line drives are the most optimal result for a batter. The first objective of batters is to reach base safely, and they did that on 67.0 percent of line drives last season. No batter who hit at least eight line drives in 2013 caused a net decrease in his team’s run expectancy during those events. For most batters, hitting the ball into the outfield in the air is the ideal way to produce value, as fly ball production tends to create a positive change in a team’s run expectancy. However, fly balls have the most variance of any of the batted ball types, and there are certainly batters who hurt their teams more when hitting the ball at a high launch angle than a low one. Here are the players to produce the lowest xRA on fly balls last season (minimum 50 fly balls):

| Lowest xRA on Fly Balls, MLB – 2013 |

|

|

|

| (minimum 50 fly balls) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pete Kozma, StL |

-.1626 |

|

|

| Ruben Tejada, NYM |

-.1546 |

|

|

| Cliff Pennington, Ari |

-.1513 |

|

|

| Andres Torres, SF |

-.1465 |

|

|

| Placido Polanco, Mia |

-.1224 |

|

|

For each of these batters, hitting the ball on the ground or on a line drive were far better results on average.

| xRA by Batted Ball Type – 2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FB |

GB |

LD |

| Pete Kozma, StL |

-.1626 |

-.0738 |

.2496 |

| Ruben Tejada, NYM |

-.1546 |

-.0961 |

.1227 |

| Cliff Pennington, Ari |

-.1513 |

-.0421 |

.3907 |

| Andres Torres, SF |

-.1465 |

-.0155 |

.4269 |

| Placido Polanco, Mia |

-.1224 |

-.0981 |

.1889 |

While groundballs may be a preferable result for some batters when compared to fly balls, they are still effectively batting failures for the team. There were 840 batters in 2013 to hit at least one groundball and only 44 produced a net positive change in their team’s run expectancy. Of those 44 players, only 11 hit more than 10 groundballs, and only two (Mike Trout and Juan Francisco) hit at least 100 groundballs. Here are the players with the highest xRA on groundballs in 2013 who hit at least 100 groundballs:

| Highest xRA on Groundballs, MLB – 2013 |

|

|

|

| (minimum 100 groundballs) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mike Trout, LAA |

.0187 |

|

|

| Juan Francisco, Atl-Mil |

.0123 |

|

|

| Brandon Barnes, Hou |

-.0076 |

|

|

| Andrew McCutchen, Pit |

-.0081 |

|

|

| Marlon Byrd, NYM-Pit |

-.0093 |

|

xR4 allows us to tell the most detailed story concerning the type of value a batter produced, independent of the situational context at the time the plate appearance occurred. Because we gradually added layers of detail to our estimation, we can compare how each level of expected runs correlates to this most detailed level. In this way, we can judge how much information each level provides with respect to our most detailed estimation. Here is a graph that charts a batter’s xR4 with respect to his xR1, xR2, and xR3 estimations:

The line that cuts through the data reflects the xR4 values charted against themselves. For each xRn, we can calculate how well it correlates with xR4 and, consequently, how much of xR4 it can explain. Remember that we have already shown that xR1 has a direct linear correlation with eOBA and xR2 has a very high, though not quite direct, correlation with eTBA. For the xR1 values, we observe a correlation, r, with xR4 of .912, and an r2 of .832, meaning that knowing the rate at which a batter reaches base explains over four-fifths of our estimation of xR4. For the xR2 values, r2 increases to .986; for the xR3 values, r2 increases slightly higher to .990.[iv]

The takeaway from this is that when considering the whole population of players, there is little difference in a run estimator that considers the batted-ball context and one that does not; you can still explain 99 percent of the value estimated by xR4 by stopping at xR3. In fact, if all you know is the rate at which a batter accomplishes his two main objectives—reaching base and advancing as far as possible—you can explain well over 90 percent of the value estimated by xR4. However, on an individual level, there is enough variation that observing the batted-ball context can be beneficial. Here are the five players with the largest positive and negative differences between their xR3 and xR4 estimations:

| Largest Increase from xR3 to xR4, MLB – 2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Player |

xR3 |

xR4 |

Diff |

| David Ortiz, Bos |

44.1 |

48.2 |

+4.1 |

| Kyle Seager, Sea |

11.8 |

15.9 |

+4.1 |

| Chris Davis, Bal |

57.2 |

61.0 |

+3.8 |

| Matt Carpenter, StL |

36.6 |

40.3 |

+3.7 |

| Freddie Freeman, Atl |

38.6 |

41.9 |

+3.3 |

| Largest Decrease from xR3 to xR4, MLB – 2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Player |

xR3 |

xR4 |

Diff |

| Adeiny Hechavarria, Mia |

-27.2 |

-32.9 |

-5.7 |

| Jean Segura, Mil |

9.7 |

4.2 |

-5.5 |

| Jose Iglesias, Bos-Det |

4.5 |

-0.1 |

-4.7 |

| Elvis Andrus, Tex |

-8.6 |

-12.9 |

-4.3 |

| Alexei Ramirez, CWS |

-1.9 |

-5.8 |

-3.9 |

These changes are not massive, and these are the extreme cases for 2013, but they are certainly large enough that ignoring them will weaken specific analyses of batting production. Incorporating batted ball details into our analysis adds a significant layer of complexity to our calculation, but it must be considered if we want to tell the most accurate story of the value a batter produced.

If this work seems at all familiar, you may have read this article that I wrote last year on a statistic that I called Offensive Value Added (OVA). For all intents and purposes, OVA and xR are identical. I decided that the name change to xR would help me differentiate estimations more simply, as I could avoid naming four separate statistics for each level of contextual detail, but there was also a secondary reason for changing the presentation of the data. OVAr was the rate statistic associated with OVA, and it was scaled to look like a batting average, much in the same way that wOBA is scaled to look like an on base average. At the time, I choose to do this to make it easier to appreciate how a batter performed, since many baseball enthusiasts are comfortable interpreting the relative significant of a batting average.

After thinking on the subject, though, I came to decide that I prefer statistics that actually “mean” something to those that give a general, unit-less rating. For instance, try to explain what wOBA actually reflects. It starts as a run estimator, but then it’s transformed into a number that looks like a statistic with specific units (OBA), while not actually using those units. Once that transformation occurs, it no longer reflects anything specific and only serves as a way to rate batters. The same principle applies to other statistics as well, most notably OPS, which is arguably the most meaningless of all baseball statistics, perhaps all statistics ever (don’t get me started).

xR and xRA estimate the change in a team’s run expectancy caused by a batter’s plate appearances. They are measured in runs and runs per plate appearance, respectively. xRA may not look like a number you’ve seen before, and generally needs to be written out to four decimal places instead of three, unlike basic averages, but it’s linguistically very simple to use and understand. I’d rather sacrifice the comfort of having a statistic merely look familiar and instead have it actually reflect something tangible. This doesn’t take away from the value of a statistic like wOBA, which is a great run estimator no matter what scale it is on; a lack of meaning certainly does not imply a lack of value. Introducing an unscaled run average, xRA, will hopefully create a different perspective on how to talk about batting production.

There is one final expected run estimation that I want to consider that could easily cover an entire new part on its own, but I’ll limit myself to just a few paragraphs. The xR estimations we have built have been constructed independent of the situational context at the time of the batter’s plate appearance. Since we want to cover the entire spectrum of context-neutral run estimation to context-specific run estimation, we will conclude by considering xRs, which is an estimate of the change in a team’s run expectancy based on the out/base state before and after the action of the plate appearance. This is very nearly the same thing as RE24 but it only considers runs produced due to the primary action of plate appearances and not baserunning events.

In many respects, xRs is the simplest run estimator to construct of all that we have built thus far. There are only three pieces of information you need to know in a given plate appearance to construct xRs: the run-scoring environment, the out/base state at the start of the action of the plate appearance, and the out/base state at the end of the action of the plate appearance. Next time you go to a baseball game, bring along a copy of a run expectancy matrix, like the one provided earlier. On a scorecard, at the start of every plate appearance, take note of the value assigned to the out/base state, making adjustments if any runners move while the batter is still in the batter’s box. Once the plate appearance is over, note the value of the new out/base state, separating out any advancement on secondary fielding errors or throws to other bases. Subtract the first value from the second value, and add in any RBIs on the play, and write the number in the box associated with the batter’s plate appearance; you just calculated xRs. Do this for a whole game, and you will have a picture of the total value produced by every batter based on the out/base state context in which they performed.

The effective averages and expected run estimations provide a foundation on which batting analysis can be performed. They combine both “real and indisputable facts” with detailed estimations of the run produced in every event in which a batter participates. Any story that aims to describe the value that a batter provides to his team must consider these statistics, as they are the only ones which account for all value produced. 147 years ago, Henry Chadwick suggested that batters should be judged on whether they passed a “test of skill.” I think they should be judged on whether they passed a “test of value.”

Thanks to Benjamin H Byron for editorial assistance, as well as the staff at the Library of Congress for assistance in locating original copies of the 19th century newspaper articles included in Part 1.

Here is data on eOBA, eTBA, and each level of xR and xRA estimation, for each batter in 2013.

Bibliography

[i] I’ll be focusing on 2013 because the full season is complete. All the work described here could easily be applied to 2014, or any other season, I just don’t want to use incomplete information.

[ii] While these terms are used a lot, there aren’t any specific definitions commonly accepted that differentiate each type of batted ball. For terms used so commonly, it doesn’t make much sense to me that they are not well defined. It won’t apply to the data used in this research, but here is my attempt at defining them.

A bunt is a batted ball not swung at but intentionally met with the bat. A groundball is a batted ball swung at that lands anywhere between home plate and the outer edge of the infield dirt and would be classified as a line drive if it made contact with a fielder in the air. A line drive is a batted ball swung at that leaves the bat at an angle of at most 20° above parallel to the ground (the launch angle), and either lands in the outfield or makes contact with any fielder before landing (generally through a catch, but sometimes a deflection). A fly ball is a batted ball swung at, with a launch angle between 20° and 60° above parallel (not inclusive), that either lands in the outfield or is caught in the air by a player in the outfield. A popup is a batted ball swung at that either (a) leaves the bat at an angle of 60° or greater above parallel and lands or is caught in the air in the outfield, or (b) leaves the bat at an angle greater than 30° and lands or is caught in the air in the infield.

This would result in some balls being classified differently than they currently are, and not just because differentiating between a line drive and a fly ball is somewhat difficult with just a pair of eyes. If the defense were to play an infield shift, and the batter were to hit a line drive into the outfield grass into that shift, subsequently being thrown out at first base, it would likely be called a groundout by current standards. Batted balls should not be defined based on defensive success or failure, but by the general path which they take when leaving the bat. It may be unusual to credit a batter with making a line out despite the ball hitting the ground, but it more accurately reflects the type of ball put into play by the batter.

I don’t know that these are the “correct” ways to group together these events, but as we now are using technology that tracks the flight of the baseball from the moment it is released by the pitcher through the end of the play, we should probably have better definitions for types of batted balls than those currently provided by MLB. I don’t expect a human stringer to be able to differentiate between a ball hit with a 15° launch angle or a 25° launch angle, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t have some standard definition for which they should aim.

[iii] In theory, xR5 would attempt to consider details that are even more specific, perhaps the initial velocity of the ball off the bat, the launch angle, and whatever other information can be gleaned from technology like HIT F/X. The xR framework leaves room to consider any further amount of detail that a researcher wants to consider.

[iv] Though not charted here, the r2 value based on the correlation between wRAA, the “counting” version of wOBA, and xR4 is .984. As wRAA is nearly identical to xR3 but excludes a few of the more rare events from its calculation, it’s not surprising that the r2 value between wRAA and xR4 is just slightly smaller than the r2 between xR3 and xR4.