Major League Baseball Should be All Over the Quantified Self Movement

This post originally appeared in slightly different form on my blog: Biotech, Baseball, Big Data, Business, Biology…

Baseball players break down. Their performances fluctuate. As a group there are some interesting generalities with respect to how pitching, hitting and fielding change with age. But the error bars are huge. There are many things we still don’t know about baseball players, about why one prospect hits the ground running and another flames out. And we also don’t know if there is any way to know, since the task of putting together the skills needed to play major league baseball may be one of the most complex of the major sports, and understanding complexity is hard.

But it seems worthwhile to give it a try.

The Mystery of the Missing Ligament

Let’s talk about R.A. Dickey for a minute. Not because he’s a highly interesting human being, although he is. And not because he’s a knuckleballer, which is fun and interesting due to rarity and the entertaining sight of six foot athletes flailing at baseballs traveling with the flight path of a drunken small-nosed bat. But rather because he was drafted in 1996 in the 1st round by the Texas Rangers, and only during his physical workup was it discovered that he was missing a key ligament in his arm. The Ulnar Collateral Ligament (UCL) to be exact. Without which, it is assumed, a pitcher cannot pitch.

Well, except that he did. This shouldn’t be under-emphasized. Pitching without a UCL is thought to be akin to trying to play tailback for the Seahawks without an Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) in your knee. And yet he pitched and pitched well for years without a UCL. RA Dickey got his UCL replaced and then knocked around the major and minor leagues for several years, eventually learned how to throw a knuckleball, and now has pitched successfully in the majors for several years more.

A story like this illustrates two points. One, we may be making assumptions that aren’t always supported by the data—for example, that the UCL is required for pitching. And two, you can learn a lot just by looking and measuring.

Measure by Measure

What should be measured and how? I think an area to look into might be the tools being developed now to support self-measurement. The quantified-self movement has gained enough prominence that magazines like Newsweek are running profiles. For people in the movement, the motivation for participation stems from a desire to better understand themselves; to have data that will give them a data-driven view of what is going on in their bodies and minds. The goals are often better health, losing weight, tracking mood, athletic prowess, increasing the levels of good indicators and decreasing the levels of the bad.

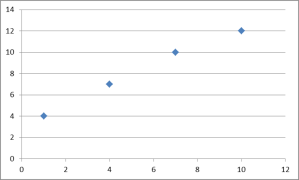

One of the distinguishing elements of how this is being done is granularity. Apps on a smartphone, portable electronic devices, and logging tools can capture data in intervals ranging from several times a day up to a more or less continuous stream. Even tests and procedures that might normally be performed once a year at an annual physical become fair game for more frequent monitoring, as long as you have the money to pay for the testing. The open question is whether collecting all of this data will reveal new insights. Or, to put it graphically, if you tested a metric infrequently, and got this graph:

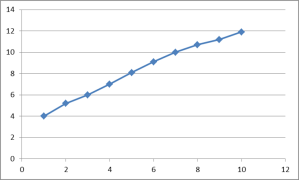

Would the result of more frequent testing look like this?

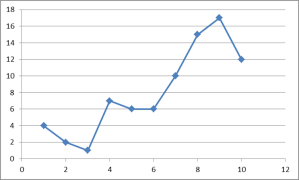

Or like this?

This example is borrowed from the site of Ginger IO, a company that is developing tools for continual measurements of health related metrics, among other things.

Where baseball comes in to this is I believe MLB teams are continually in a search for new ways to gain an advantage in building a quality team. You know, that extra 2%. A baseball team has vast resources, and those resources are focused on getting the most out of the several hundred baseball players that comprise the major and minor league talent of the team. There are trainers, and doctors, and team dieticians, and masseuses, and coaches. What would it take to add an additional technological and analytical group dedicated to gathering data on the players and seeing whether any of this information provides additional retrospective or prospective insight into individual performance?

Here is where an enterprising team could probably reach out to a couple of different groups for help in setting this up. One would be device and software manufacturers who are building tools in this space. I’ve written before about EmotionSense and have also learned recently about GingerIO (HT to @Dshaywitz). Another highly interested party would be the nearest medical school and those researchers looking into patient reported outcome (PRO) techniques and patient monitoring efforts. If an MLB team doesn’t already have its own high-powered statistical analysis group (or even if it does), it could reach out to suppliers of software tools for analyzing large scale datasets and finding patterns, like Ayasdi or Google.

I could also see a viable group for a partnership being other professional sports teams. Many MLB teams are in the same city as NFL, NBA, NHL, and/or MLS franchises. To spread the investment costs as well as providing control groups for each other, it would be useful to collaborate with these other franchises to learn more about the effect of sports training in general.

A speculative area for data collection and analysis could be in genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics. Michael Snyder of Stanford University has been demonstrating for some years now how a program of monitoring personal molecular information about one’s health, along with other more conventional measures, provides new insights into health and disease.

The metrics should also include the conventional. Going back to the example of R.A. Dickey, wouldn’t it be useful to perform elbow and shoulder scans for every player on major and minor league rosters on at least a yearly basis? So often in sports you hear the term “typical wear and tear” when describing an elbow or shoulder or knee. My question is, how do you know it’s typical? Until you have a large, well-defined baseline that you follow for years under the rigorous conditions that baseball players are subjected to, how can you know what real wear and tear is? And if you did know, wouldn’t that help you in making decisions about training and protecting your own players, to say nothing of evaluating free agents? One of the truisms of baseball is that every team knows more about their own players than anyone else, leading to information asymmetry in trading and signing. It seems an imperative for each team to reduce or reverse that asymmetry if at all possible.

An additional area that personal monitoring could help in is understanding on-field performance. I’ve already touched on how MLB could use various kinds of GPS and positioning sensors to more accurately measure defense, for example, so I won’t elaborate further except to point out Chip Kelly is bringing this approach to the Philadelphia Eagles, and it will be interesting to see if we get reports on the effectiveness of using GPS to monitor his NFL players’ movements.

Biological passports

Another benefit of building a baseline for different kinds of metrics in your team would be helping to detect the possibility of doping. This seems to be in the news right now for some reason, so let me just say that if a team began collecting, analyzing and storing biological samples on a regular basis, this would help in detecting those who are taking performance-enhancing substances. This isn’t a new idea; the World Anti-Doping Agency is advocating this approach already. However, I think MLB could take it to a high level of rigor and quality. Would this have to be negotiated? Sure. But there is probably no better time than now to see if such an agreement can be forged between the union and the MLB owners.

Essentially, by taking samples from enough players over time, as well as healthy, age and ethnicity-matched volunteers as a control group, an MLB team could build up a comprehensive profile of what normal is with respect to the known indicators of performance enhancement such as hemocrit levels, not just as an average, but on an individual basis. With this kind of data, a rapid, unusual change in specific metabolites could provide grounds for more intensive investigation. When athletes come up with a positive test, a standard argument has been that he or she always has had an unusually high level of the tested substance. Well, you know, the only way to know that for sure is to have a record dating back years that demonstrates outlier status or not for that athlete and that test. Continual sampling is almost certain to deter many would-be attempts to use performance enhancing substances.

This would be invasive. No doubt about it. Which is why there should also be stringent controls on data and better maintenance of privacy than we’ve seen so far in the Biogenesis saga. However, there is also probably no better time to negotiate these kinds of tests as baseball strives to clean its image again.

Too much data?

Of course, collecting all this data provides no guarantee of actually finding out something specifically useful and actionable for any given MLB team. As Nate Silver has pointed out many times in his columns and book, given enough data you can find a correlation for almost anything. However one thing is certain: you can’t find new things when you don’t look, and trying to apply concepts of the quantified self to MLB teams will lead to a whole lot of cross-discipline interactions and innovative thinking, which a forward-looking team might be able to parlay into the next big market inefficiency in baseball.

I think this is the most interesting idea in this piece:

So often in sports you hear the term “typical wear and tear” when describing an elbow or shoulder or knee. My question is, how do you know it’s typical? Until you have a large, well-defined baseline that you follow for years under the rigorous conditions that baseball players are subjected to, how can you know what real wear and tear is? And if you did know, wouldn’t that help you in making decisions about training and protecting your own players, to say nothing of evaluating free agents?

I’ve never thought of this before, but it’s a great point.

When I wrote this piece, part of what I was thinking of is I had heard the Giants were doing something like this with their minor league pitchers. However, I wasn’t able to find specific information.

I do think there are two questions: what is normal, and is that predictive? Kind of like PECOTA for joints.