Jacob deGrom’s Encouraging Adjustment

Jacob deGrom struck out 10 batters in his fourth start of the 2017 season. He also walked six and gave up three earned runs on eight hits. The statline alone might tell you it was his weirdest game of the year, and maybe his worst.

Before that, in his third start, he went seven innings and struck out 13. He allowed back-to-back dingers early and then took control of the game, allowing only three more baserunners the entire night. His pitches were humming like a barbershop quartet. That statline makes it sound like his best start of the year.

But it wasn’t.

No, that would be his second turn, on April 10 at the Phillies, where he only struck out three. He also walked two and gave up six hits in six innings. That sounds terrifically pedestrian until you realize how he did it.

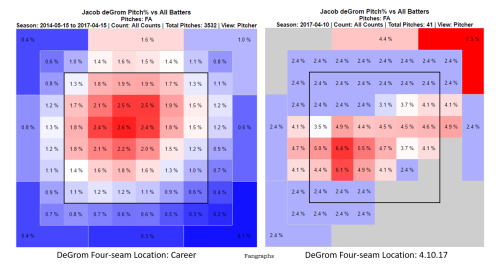

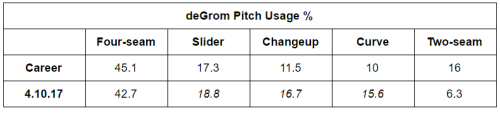

We can start with his fastball, which was a big reason he labored through 31 pitches in the first inning (he only threw 96 all night). Compared to where he’s located it through his career (left), it was all over the place that night (right). It contributed to six men reaching base in the opening frame. He also gave up both walks then, one of which came with the bases loaded. And then Brock Stassi came to the plate and worked a 2-2 count. deGrom threw a changeup, induced an inning-ending double play, and transformed for the rest of the night.

Equal pitch distribution is always interesting. It can speak to a lack of predictability and according effectiveness. But seeing it so even among the slider, curveball, and changeup in this way is more than interesting; it’s relatively unprecedented. Historically, I couldn’t find anyone whose pitch mix has broken down that way for their career.

That’s significant for a few reasons. First, it could explain why Phillies hitters ended up struggling when deGrom seemed to be on the ropes. I could hardly believe they didn’t do more damage as Stassi hit into the double play. But the rally faltered because deGrom had already started to adapt, and in a way that hitters simply aren’t exposed to. In that context, and considering the Phillies aren’t exactly Murderer’s Row, it’s not so strange.

The slider-change-curve pitch mix also speaks to the importance of an effective fastball. With an unreliable four-seamer, deGrom basically ignored his two-seamer. Maybe he did that because if he couldn’t locate the straight one, he figured the alternative that has four to five more inches of movement was no good, either.

But more than anything, deGrom’s adjustment that night was compelling because we’re in an age of sport where we constantly hear about guys unleashing their egos to achieve eminence. And he went the other way.

Alec Fenn of BBC delved into ego’s place in sports. He spoke with confidence coach Martin Perry, who tells how some of the most exceptional players “don’t see risks; they have a bulletproof certainty they’ll produce and [with that] supreme level of confidence, magic can happen.”

Perry compares ego to the stuff of Harry Potter and Disney World, around which entire entertainment universes have been built. For all the mystique ego can produce, it’s no wonder we speak about it so lustfully and embrace it so openly.

A pitcher is provided more opportunity to drive a game with his ego than any other player because of his involvement in every play. On that night in Philadelphia, Jacob deGrom was determined to assert himself and beat the Phillies by establishing his fastball, as any pitcher would try. When it didn’t work, he walked away from his ego but maintained bulletproof certainty. He went with the flow. He didn’t get the win but was a huge reason the Mets did, and gave us a glimpse at an alternative route to success in the process.

—

data from FanGraphs

Tim Jackson is a writer and educator who loves pitching duels. Find him and all his baseball thoughts online at timjacksonwrites.com/baseball and @TimCertain.