Another Thing Joey Votto is Great At

If you walked up to me and said “Joey Votto is the best player in baseball”, I’d have a hard time finding a good argument against that. Heading into his twelfth season, Votto has been one of the most consistent players in the league. From 2007 on he’s played at least 110 games each year, with the exception of his rookie year and the injury-shortened 2014 season.

Using a summary of his last three years, you’ll see he’s been at or near the top in almost every major statistical category used to evaluate players.

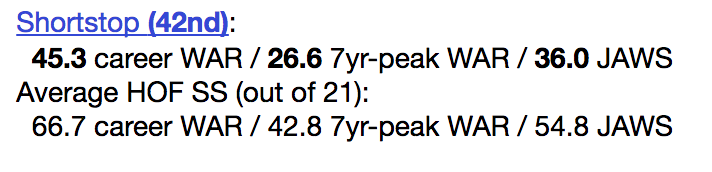

- Fourth in overall WAR

- Second in Batting Average

- First in On Base Percentage

- First in BB/K rate

- Third in Win Probability Added

- Second in Weighted Runs Created Plus

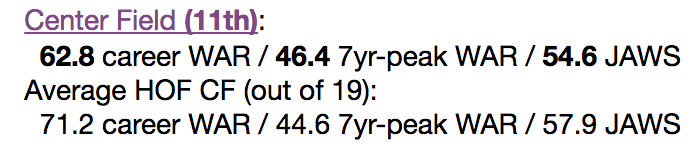

Does Votto leave anything to be desired? Well, of qualified first basemen, he ranks 12th in DRS (3) and 16th in UZR/150 (2.6) since 2015. So if you could get on him for anything, it would be his fielding.

Hitting a baseball is one of the hardest feats to accomplish in any sport. I would venture to guess, whether you’re the pitcher or hitter, that a full count creates the most tension on the baseball field. I don’t think it takes a Bill James-like brain to figure out that 0-2 is a very tough situation to be in at the plate; the scales tipped heavily in the pitcher’s favor. Game tension is a fun energy to experience in baseball, which leads me to stick with looking into the more balanced full count.

Would you be surprised if I told you that no one has performed better in recent seasons under those conditions than Votto? But first, behold the predictable OPS under all two-strike counts!

- 0-2, .389

- 1-2, .419

- 2-2, .470

- 3-2, .814

Digging into the specifics of a full count, 30% of hitters get walked and 46% reach base. Votto is one of those 46%-ers. In fact, since 2015, no other hitter had a better wOBA under a full count than Votto.

Pretty impressive at the plate to begin with, every aspect of Votto’s at-bats are above average; needless to say, you’re going to have your work cut out for you when he comes to bat.

Votto has an advanced eye, which you can tell by only looking at his swings out of the zone; at least 10% lower than league average. On the other hand, he seems to make contact more than average when offering at those pitches. But, only achieves a paltry .219 when putting the ball in play. Regardless, pitchers have to be pretty careful with what they do to get him out lest he ends up on base and/or putting crooked numbers on the scoreboard. We’ll get to that in a minute.

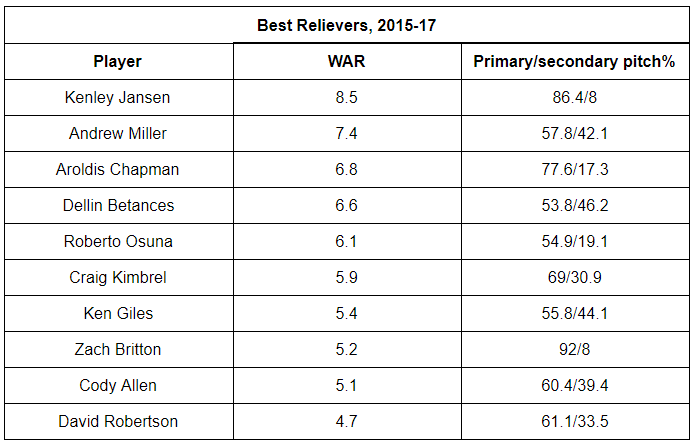

Getting back to his production with a full count, we have three other hitters within reach of Votto. The qualifying threshold is 200 at-bats (regular and postseason), of which 28 hitters qualified. The following are tops in wOBA when faced with a full count. After that foursome, there is a very sharp drop off.

- Votto- .481

- Matt Carpenter- .480

- Kris Bryant- .467

- Mike Trout- .461

Votto and Carpenter are very close, one one-thousandth of a point, but Votto has been in this position 111 times more. The averages keep them close but there is no way to be certain Carpenter could keep that number consistent as his at-bats go up.

No real correlation there but Votto and Bryant are the clear outliers; Carpenter and Trout are with them as well but are a bit further back in terms of pitches.

Votto also has the highest percentage of 3-2 counts in terms of pitches faced with 7.12% of his pitches being delivered in that situation; again with a minimum of 200 ABs. That’s an attribute to his plate discipline.

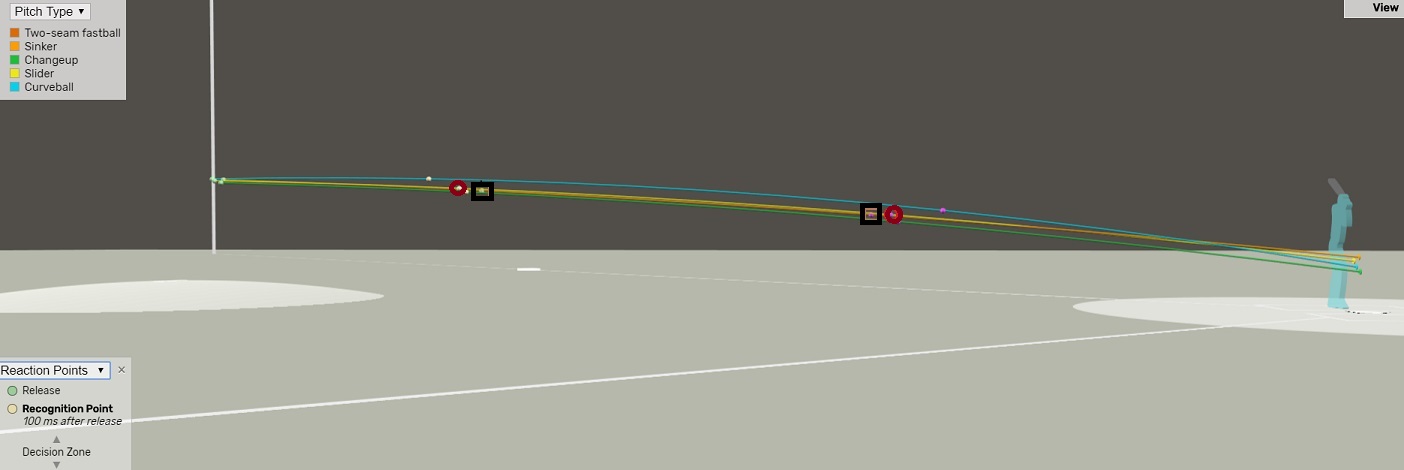

So how has he been so successful? This is where things get interesting. When Votto is faced with a 3-2 count, look where the pitches he has to work with are concentrated.

Furthermore, take a look at his career batting average based on zone location.

For whatever reason, pitchers seem to be content delivering a 3-2 pitch right into Votto’s butter zone. To be specific, the three pitches thrown at him the most in a full count are:

- 34.8% Four-seam Fastballs

- 17.2% Two-seam Fastballs

- 17% Sliders

- 9% Changeups

Almost half of the pitches thrown are fastballs of the two and four-seam variety. Guess what Votto eats up?

Those are the pitches Votto has seen the most since 2015. Coincidently, they are not only the four he sees most in 3-2 counts but also, with the exception of the slider, the pitches he has the most success against.

There are some pitchers don’t throw a slider but what I don’t understand is why they try to beat him with a fastball almost 50% of the time. It obviously doesn’t work. I’ll try to quantify as best I can, the situations Votto comes to bat under. Just going on what I have in the previous charts, maybe there aren’t many high-leverage situations when its Votto’s turn to hit.

For his career, he’s come to the plate 2,683 times with runners on base; 1,528 of those are with runners in scoring position. For the former, his OPS is 1.026 and the latter 1.079.

To give context to how much more/less Votto comes up with runners on base, I used the 2015-2017 average season numbers of total at-bats and divided that by 750. The 750 is 25 players per 30 teams. That’s a loose guesstimate but I would presume that through a given season a team holds at least that many (different) hitters on average, taking into consideration promotions/demotions/injuries/etc. That gave me 107 plate appearances per season with runners on base for the average hitter.

Then I used Votto’s career 2,683 PAs with runners on and divided it by his 11 seasons to get an average of 244 PAs per year. So, he has runners on about 44% more than the average hitter each season. Where he hits in the order DOES help but you have to remember he’s been playing on, for his career, a pretty mediocre Reds offense.

And, as a footnote, his worse performances are with runners on second and third followed by bases loaded; he excels with runners only on second, third, or first AND second.

That tangent we just went on only answered part of the question. We can’t know what the score was, the leverage index and other minor variables. All of those could change the way Votto is pitched to given the particulars. But, for whatever reason, the best hitter in baseball under a full count does not seem to be challenged much at all.

This post and others like it can be found over at The Junkball Daily.