The Curious Case of Carl Crawford

On December 8, 2010, the Boston Red Sox agreed to terms with Carl Crawford, inking the outfielder to a seven-year, 142-million-dollar deal, the largest ever signed by a position player that had never hit more than 20 home runs in a single season. Although the majority of the population felt that the Red Sox had overpaid for his services, most considered it only a slight reach, and when factoring in Boston’s position on the win curve, their decision to splurge on a premium player could be justified. Crawford was an established elite defensive outfielder coming off the best season of his career at the plate; an increase in power prior to the 2009 season had boosted Crawford to new heights just in time for his pay day, and in the final two years of his extension with the Rays, he posted WARs of 5.9 and 7.7, respectively. In the immediate aftermath of his signing with Boston, FanGraphs’ own Dave Cameron declared him to be a true-talent 5-win player, and at the time, it was not difficult to imagine a scenario in which the 29 year-old Crawford continued to perform at peak levels before gradually declining in the final years of the contract. If we assume that Crawford was in fact a 5-win player, then using the $/WAR figure accepted in the winter of 2010 (5 million dollars/win), 5% inflation, and a standard aging curve, the projection for Crawford’s contract would have looked something like this, with his 6-million-dollar signing bonus excluded from the analysis:

Two things are striking when looking at this table. First, on an unrelated note, league-wide inflation as a result of TV deals and increased revenue streams has far exceeded the expectations of 2010, actually surpassing 10% in order to reach the accepted value of 8-9 million dollars per win today in 2016. Although the methodology did prove to be incorrect, I do still believe the results obtained here to be worthy of inspection, as they offer insight into teams’ valuations of Crawford as a player available in the free-agent market. Second, the divergence between industry consensus and the arithmetic presented here is worth noting; most insiders felt that Boston had spent too much, while the data presented here suggests that the contract actually provided a bit of upside. This disparity could perhaps be explained by a skepticism of defensive metrics in 2010, along with doubts about Crawford’s ability to age well, as a large portion of his value on the bases and in the outfield was tied up in his legs. In order to account for this discrepancy, perhaps it is better to use a “worst-case scenario,” to subject Crawford’s performance to a more punitive aging curve over the life of the contract. Instead of docking Crawford 0.5 WAR for his age-31 through -35 seasons, instead, he will lose 0.75 wins each year. This steeper decline is forecast below:

It appears that this table is a more accurate representation of front offices’ opinions about Carl Crawford, as shown by the deficit in the bottom right corner. Using the more aggressive aging curve, the contract offered by the Red Sox does appear to be a slight overpay, and if they conformed to the opinion that the outfielder would decline more swiftly than other players of similar age, then they agreed to a contract in which there was no upside. However, if Crawford’s performance fell anywhere between the standard aging projection and the “worst-case scenario,” as it was likely to, it seemed that both sides would be satisfied with the outcome.

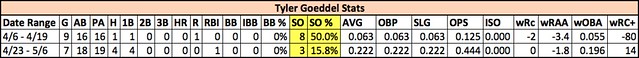

As we all know now, this “worst-case scenario” projected in 2010 was a far cry from reality. After suffering through a tumultuous year and a half in Boston and undergoing Tommy John surgery to repair a partially torn UCL, Crawford was unceremoniously dumped by the Red Sox and shipped to the Dodgers on August 25, 2012 as part of the infamous Nick Punto trade. It appears that Crawford has finally hit rock bottom, with Los Angeles designating him for assignment on Sunday. Crawford will almost certainly clear waivers, and assuming he asks to be released rather than assigned to the club’s AAA affiliate in Oklahoma City, the Dodgers will eat the remainder of his contract and essentially pay Crawford nearly 35 million dollars to disappear. Rather than projecting future performance, let’s instead take a look back at Crawford’s production since signing with Boston:

Although up-to-date $/WAR figures could have been used, I stuck with the estimates of 2010, in order to further emphasize how poorly this pact has been when compared to the organization’s expectations when they chose to sign Crawford. Elbow injury notwithstanding, it is difficult to imagine how this contract could have soured so quickly. Crawford has already cost his employers 85 million dollars more than his production would have warranted, and even if he latches on somewhere and plays out the remainder of the deal, it’s very likely that figure ends up more than 100 million dollars in the red. So, how did this happen? How did Carl Crawford, he of the 7.7 WAR in 2010, second in all of baseball, flop so badly, producing only 5.3 WAR since signing with the Red Sox?

Well, the most obvious answer is the boring one: Carl Crawford got old. Fast. From 2008-2010, Crawford’s final three seasons in Tampa Bay, he was actually the best defensive player in the MLB, posting a UZR/150 of 20.6 in left field, two runs better than his nearest competitor on the leaderboard. A bit of regression and decline were certainly expected, as it is incredibly difficult to sustain this level of performance, but nobody could have expected the utter evaporation of his defensive value upon arriving in Boston. Crawford posted a negative UZR during his time patrolling the Green Monster; some criticize the Red Sox for wasting his defensive abilities in what is considered to be the smallest left field in all of baseball, suggesting that he should have been moved to Fenway’s right field in order to better leverage his extraordinary range. However, even before his elbow injury, Crawford was known for having a weak throwing arm, and with a partially torn UCL, it would have been nearly impossible for him to play anywhere other than left.

Even so, his damaged elbow fails to explain the mysterious loss of range that sent him tumbling down the UZR leaderboards, and instead of providing value as an elite defensive player, Crawford instead resembled an average corner outfielder during his time in Boston. After being dealt to Los Angeles, Crawford’s defensive numbers did improve slightly, perhaps indicating that he never felt comfortable playing in front of the 37-foot wall, but by the time he arrived in Chavez Ravine, Crawford had already lost a step or two, placing a ceiling on his future defensive contributions.

This loss of speed was evident on the base paths as well, with Crawford never again imposing his will upon opposing batteries like he did during his time with the Rays. From the time of his promotion to Tampa Bay in 2002 until the end of 2010, Crawford had stolen 409 bases in 499 attempts, for a success rate of nearly 82% and the second-highest stolen base total in all of baseball during that timeframe. However, after signing with Boston, it seems as if Crawford became more timid as a runner, never attempting more than 30 steals in a single season. Since 2011, Crawford owns a 79% success rate, quite similar to his career average, yet he’s running far less frequently, stealing only 71 bases in 90 attempts. Whether due to a loss of speed or a lack of aggression, or perhaps a combination of the two, Crawford never regained his form as a base-stealer, resulting in the loss of a huge chunk of his base-running value.

Unlike his collapse in the outfield and on the base paths, Crawford’s decline at the plate cannot be explained by a loss of speed simply chalked up to age. This dilemma is a bit more perplexing. After posting the two best seasons of his career at the plate in Tampa Bay immediately prior to hitting free agency, Crawford’s production in the batter’s box cratered after signing with Boston in 2011, falling to levels only experienced by the outfielder during his first full season in the majors in 2003. Since joining the Red Sox, Crawford has sported a more aggressive approach leading to fewer walks and more strikeouts, has exhibited less power than he did during his time in Tampa Bay, and his problems against left-handed pitching have only been exacerbated. In a vacuum, none of these changes themselves would be damning, but in conjunction with one another, this trio has formed a nasty combination, only hastening Crawford’s demise.

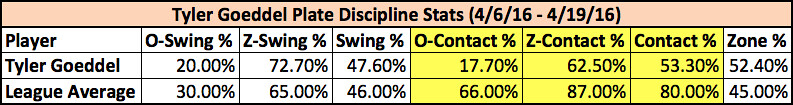

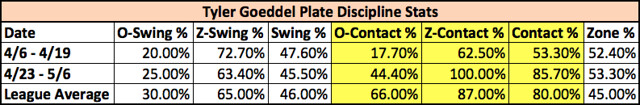

Starting in 2006, as Crawford entered his offensive prime and started to become a force at the plate, his Zone%, the number of pitches he saw in the strike zone, began to decline as pitchers decided to carefully pitch around him rather than challenging him, falling from a high of 57% to only 43% in 2010. During his MVP-level campaigns in 2009 and 2010, Crawford adjusted to these changes appropriately, cutting his swing rate and accepting the free passes being handed to him by opposing pitchers, adopting what could be considered somewhat of a slugger’s profile. However, in 2011, perhaps feeling the weight of his new contract and worrying that hits rather than walks were needed to justify the nine-figure deal and appease Boston fans, Crawford gave these gains back, as his O-Swing% jumped by nearly three points.

Surprisingly, Crawford actually controlled the outside corner of the plate, but he expanded the zone in nearly every other direction. By chasing balls rather than selectively punishing mistakes, Crawford effectively got himself out more than ever, posting a career-high K% and his lowest BB% since 2003. Even when Crawford did make contact, the quality was often terrible, as his Soft% rose to a nearly unfathomable 26%, contributing to a 40-point drop in his BABIP and a subsequent, almost identical, fall in batting average. Although some of the walks have returned since his horrendous 2011, Crawford’s strikeouts remain elevated, seriously limiting his offensive production.

The lack of quality contact has also affected Crawford’s power output, because although his fly ball and line drive tendencies have been in line with his career norms, Crawford is doing far less damage. During his time in Tampa, Crawford had an ISO of .148, peaking at .188 in 2010. In Boston and Los Angeles however, this number has fallen to .136, and he’s never posted a single-season ISO higher than .150.

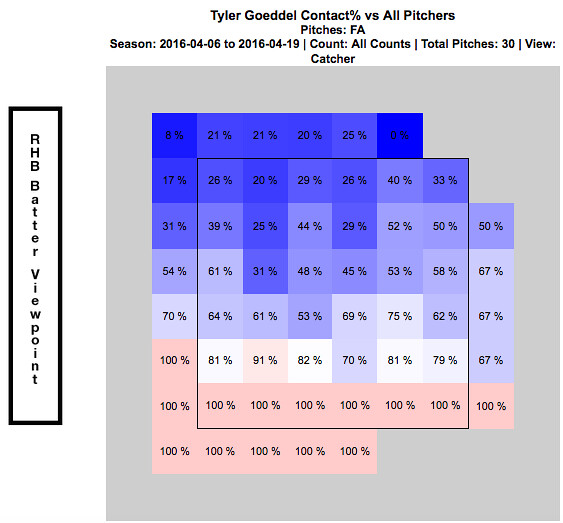

This loss of power is most obvious at the top of the strike zone and on the outside corner, where Crawford is now capable of doing little to no damage. Even in his wheelhouse, down and in, Crawford’s strength has eroded, leaving him as a shell of his 2010 American League MVP candidate self at the plate.

Finally, and perhaps most troubling, since leaving Tampa Bay, it seems like Crawford has forgotten how to hit left-handed pitching. Even in his prime, the lefty struggled against southpaws, boasting only a .308 wOBA, but since signing with Boston, his production against same-handed pitching has collapsed, with his wOBA falling nearly 30 points, leaving with him with a wRC+ of 73 against lefties. And yes, we now have an answer, his platoon split absolutely matters. The final straw came in 2013, when he posted an ISO 0f .084 and a wRC+ of 56 in 115 plate appearances against left-handers; since then, Crawford has become a platoon outfielder, almost never allowed to face lefties and failing miserably when he does, as evidenced by his -64 wRC+ against them this year (granted, in only 12 plate appearances).

So, there you have it. Carl Crawford, the electric baserunner, phenomenal outfielder, and prodigious hitter of less than six years ago is soon to be unemployed, assuming he clears waivers and is released. Does he have any baseball left in him, or is this 142-million-dollar man done? In any other year, he might have been, but given the number of contenders that will need an outfielder and the limited supply, it’s very possible that a team will give him a chance. However, it is unclear if Crawford even wants to continue playing, given that the team acquiring him will almost certainly place him in a platoon role, while he has stated that he doesn’t believe he is a platoon player. If he does agree to play in a limited role, where could he land? An obvious answer is Cleveland, yet during his time in Boston, Crawford didn’t get along well with current Indians’ skipper Terry Francona. Somewhat comically, Boston is another obvious fit, as he could be a nice platoon partner for Chris Young, but we all know how his first stint with the Red Sox went. Other teams that could be interested in the outfielder’s services include the Orioles, Nationals, Mariners, and White Sox, although they may look to make a bigger splash before settling upon Crawford. Whether Crawford returns to the big leagues or not, his time as an impact player almost certainly ended years ago, and that’s a shame.

No matter their team allegiance, fans of the game of baseball have to be disappointed by the outcome of Crawford’s career, as his prime was gone far too soon. One of few players that could truly dominate the game in every phase, through a combination of injury, age, and perhaps a lack of mental toughness, Carl Crawford’s star was extinguished almost immediately after signing with Boston.