Vince Velasquez Needs a New Approach, and He Knows it

When the season started I said that Vince Velasquez would be the future of the Phillies…if he could wrangle his fastball usage.

He hasn’t. And after only the first quarter of the season, that might not seem quite newsworthy. His last start was pretty much exactly what we’ve come to expect from him: 6 strikeouts, 2 walks, and 5 earned runs in 5.1 innings. But after the game Velasquez said, “I don’t know. I’m just clueless right now. I’m just running around like a chicken without a head.”

Those are the comments of a player worn down by his own consistent, tepid performance like running water does to the sides of a canyon. Manager Pete Mackanin had his own thoughts after the game. Per Corey Seidman of CSN Philly:

“He just has trouble commanding his secondary pitches,” Mackanin said. “He needs to command his secondary pitches. Once he does that, hitters can’t sit on his fastball. He’s got a real high swing-and-miss percentage on his fastball. I think he’s second to (Max) Scherzer.

“Players don’t square up his fastball but when you can’t command or show the command of your secondary stuff, then they just keep looking for the heater. And if you make mistakes with it, it gets hit. So his challenge is to start gaining better command of his breaking balls.

“If he throws a slider to a hitter and he swings and misses at it and it’s out of the strike zone, he’s got to have the ability to throw another one in the same location instead of just throwing a fastball.”

As of this writing, the Phillies have lost 19 of the last 23 games. They’re in the middle of a rebuild, a phase where they’re expecting the first wave of the next generation to start producing. Velazquez is a critical piece. With how the big picture and current moment are swirling, Mackanin’s comments are worth examining.

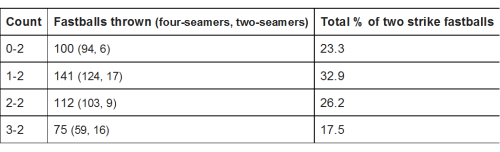

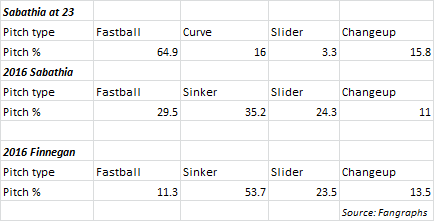

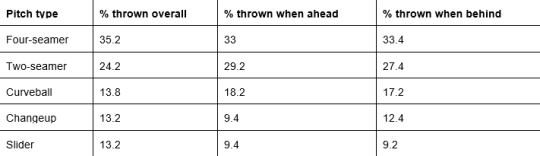

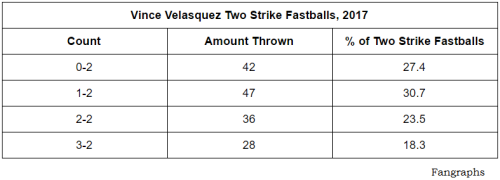

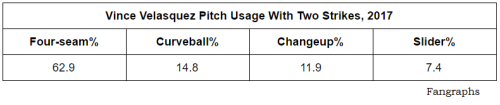

Yes, Velasquez needs to throw less fastballs. His approach is nearly identical to last year. In fact, with two strikes, he’s throwing the heater more often. Given that, even having command of his secondaries may not influence his results much.

And we may not be in a position to say he’s not confident in his secondary offerings because he’s thrown them so irregularly. He’s employed his fastball at least four times more than all of his secondary pitches in two-strike counts this year.

The relaxed environment built by the team seems to have enabled certain guys to grow into, or maybe even outgrow, expectations. Freddy Galvis, Odubel Herrera, and Cesar Hernandez all fit that description. But Velasquez could require additional structure. There might already be a successful player in the league to use as a template, too: Chris Archer.

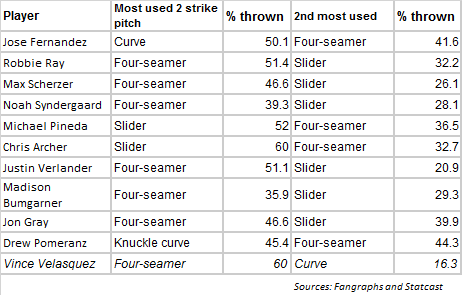

Archer is mostly a two-pitch pitcher. His fastball (used 47.4% of the time this season) and slider (45.1%) account for nearly every pitch he’s thrown in 2017. He sprinkles in a changeup (6.6%) as the game goes on to keep hitters honest when they see him a second and third time. He’s used his slider in two-strike counts this year just about as much as Velasquez has used his fastball, so there’s already some semblance of a formula Velasquez knows that could help him transition his mental approach.

By movement, Velasquez’s slider is basically a flatter, faster version of his curveball. It hasn’t been effective. He’s thrown it less this year than last, but further reducing its use would leave him with an electric four-seamer, a sharp curve, and a solid changeup.

The repertoire would be different from Archer’s, and the effectiveness of its differences could be debated, but the goal would be straightforward: simplify Velasquez’s game, so that when he does find himself in a two-strike count, his fastball could play up like Archer’s slider. Get him out of his head and let his stuff do the talking because it is capable of speaking for itself.

Once he feels comfortable with this strategy, Velasquez could add to the velocity gap between his fastball and changeup, which could provide some much-needed guile to his game. And while it might seem foolhardy to think of step two of a plan for a struggling player before they even start step one, it’s vital, because he’s never had more than one step to his approach.

It’s been apparent for some time that Velasquez throwing only the fastball wouldn’t be enough, no matter how good it is. Now we know he knows it, too, and we’re all waiting for the next step.