The Art of Doubling to the Pitcher

Kendrys Morales and Gerardo Parra aren’t two players you tend to think about together. Parra is an elite defensive player with solid offensive skills and Morales is a slugging DH. Parra walks a little bit more and strikes out a little bit less, but Morales makes up for that differential by slugging about 80 points higher. Parra stands right around average at the plate in 2013 with a 99 wRC+ and Morales is above average at 138 wRC+. They’re both valuable in different ways, but they are also the only two players to date in 2013 to be credited with an extra-base hit to the pitcher.

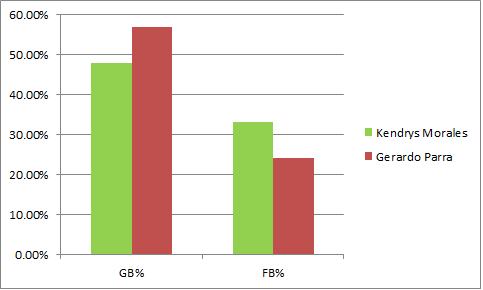

Their batted ball profiles are quite different as Parra tends to put the ball on the ground and Morales makes his money in the air.

Parra swings more often and makes more contact along the way, but Morales seems to hit the ball with more force considering his higher home run total in a less hitter-friendly park. These are two players who aren’t all that similar but happen to be the only players to accomplish one of the stranger feats in baseball during the 2013 season.

Up front, it’s important to know this comes from Pitch F/X classifications, meaning that the play had to be scored a double, triple, or home run and it had to be fielded by the pitcher or hit into his zone. I don’t know exactly how the latter determination is made but I will assume that there aren’t massive mistakes in classification. I’ve watched Parra and Morales’ hits to confirm, but I obviously haven’t watched every double this season to make sure there aren’t any missing points.

What’s wonderful about these two extra base hits to the pitcher (both doubles) is that they match the respective players so perfectly.

May 5, 2013 – Mariners at Blue Jays

With Brandon Morrow on the mound Morales came to the plate in the Top of the 8th inning and worked a 1-1 count. Amazingly, before Morrow could throw his 3rd pitch of the at bat, a fan ran onto the field and stopped play. I have no idea if that was responsible for what happened next, but the coincidence is too hilarious not to mention.

When play resumed Morrow came at Morales with an 85.7 MPH slider which the Mariners’ DH hit way up into air. With the roof open and sun beating down, the infielders converged toward the back of the pitcher’s mound to field the routine pop fly.

There are three professional athletes within 10 feet of where the baseball is going to land and they are all close enough to make the play quite easily. However, things take a comical/terrible turn depending on your personal feelings toward the Blue Jays.

As you can see, hopefully, Encarnacion called the ball vigorously and then fell over causing the third baseman to jump out of the way and lose sight of the ball, thus removing any hope of catching it himself. The baseball bounced about 10 feet into the air and Morales, who had been hustling, cruised into second base.

Morales hit his double to the pitcher in a very Morales fashion. He hit a fly ball and the defense didn’t catch it. The fan who ran on the field may have been in the minds of the players, but it’s more likely Encarnacion was trying so hard to fight the sun that he forgot about the hill located in the center of the diamond.

May 14, 2013 – Braves at Diamondbacks

In the Bottom of the 3rd, Cliff Pennington stood on first base and Julio Teheran climbed onto the mound. Parra dug in and took the first two pitches for balls, putting him into a nice hitter’s count. On the next pitch, Teheran delivered an 89.3 MPH fastball with some nice tailing action that Parra slapped to the right side.

You can see the baseball came right between the pitcher and first baseman as neither could make the play on the weakly hit bouncer. Generally this situation should result in a respectable infield single. After all, if I hadn’t prepared you, it would seem likely that the second baseman would pick up the ground ball and hold the runners at 1st and 2nd. You can see the third baseman is manning his position and just off the screen I assure you the shortstop is doing the same.

However, it didn’t exactly happen like this. Dan Uggla over-ran the ball, perhaps because he was expecting to run to the bag and couldn’t decide quickly enough to change course.

As a result, the pitcher had to back up the second baseman on a ground ball as Parra hustled into 2nd base.

This strikes me as a very Gerardo Parra type of hit. He put it on the ground and used his legs to turn it from an infield single into an infield double. It required a defensive mistake, but it was a defensive mistake that was, in part, forced by his ability.

Didi Gregorius singled in the next at bat to plate the Dbacks only two runs of the game, which also happened to be decisive in their win over the Braves. The final score was 2-0, so Pennington would have scored the winning run even if Uggla made the play on Parra, but it’s possible the defensive implosion took focus from Teheran or simply exhausted him given how far he had to run to make get the ball and resulted in poorer pitches

Nothing came of the Morales double as the Mariners didn’t score and went on to lose 10-2 despite that double coming as a result of much more egregious defensive play. Parra was going to have a single unless the Braves made an excellent play, but Morales shouldn’t have been on base at all. Apparently, the Baseball Gods agreed and didn’t punish Morrow as much as Teheran.

Baseball is often remarkable for the strange things you see. If you had to guess which two players doubled to the pitcher in 2013 you probably wouldn’t have picked Morales and you probably wouldn’t have expected that neither case involved someone failing to cover second base. This is one of those wonderfully weird moments in baseball that ties together to very different players with an odd set of circumstances.

Twice this season a player has doubled to the pitcher and both times that player did so in a way that was partly in line with their style of play, but both were very different. In one case the play was critical to the outcome and in one case it was meaningless.

Doubles to the pitcher are rare as a database search going back to 2008 reveals these as the only two. They happened nine days apart and are the only extra-base hits to the pitcher recorded by Pitch F/X in the last six seasons. Next time something like this happens, maybe the batter will try to stretch it into a triple in order to have an honor all his own.