Evaluating the Gap Between ERA and FIP

Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP) has displayed an ability to accurately measure a pitcher’s true skill. FanGraphs describes FIP succinctly as “a measurement of a pitcher’s performance that strips out the role of defense, luck, and sequencing, making it a more stable indicator of how a pitcher actually performed over a given period of time than a runs allowed based statistic that would be highly dependent on the quality of defense played behind him…”

This definition recognizes three factors that may differentiate the runs a pitcher is expected to surrender (FIP) versus the runs a pitcher actually surrenders.

- Defense

- Sequencing

- Luck

FIP removes these factors by only measuring the events that are within control of the pitcher and therefore accurately reflect the skill of the pitcher. These events are strikeouts, walks, batters hit by pitch and home runs. All other events, which are balls put into play, may result in outs, bases, runs, or errors, but are outside the pitcher’s complete control.

The general measure of over- or under-performance of a pitcher’s true skill is ERA-FIP. ERA measures the earned runs given up by a pitcher based on all the events that happen, opposed to FIP’s measurement of runs given the limited events over which a pitcher has complete control. Therefore, the variance between ERA and FIP is attributed to the three factors noted above: defense, sequencing and luck.

But how much of the difference between pitching results and pitching skills are attributable to defense, sequencing, and luck, respectively? And shouldn’t the opponent get some credit for widening the gap between ERA and FIP, either to the benefit or detriment of the pitcher?

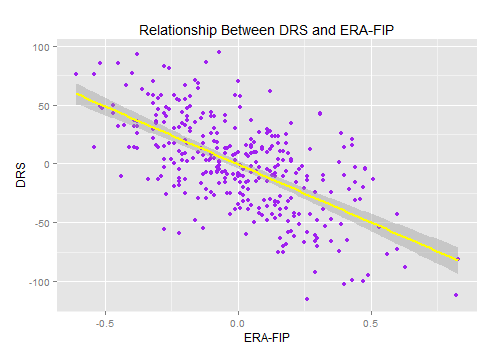

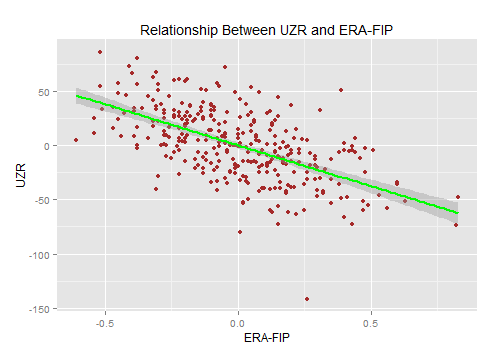

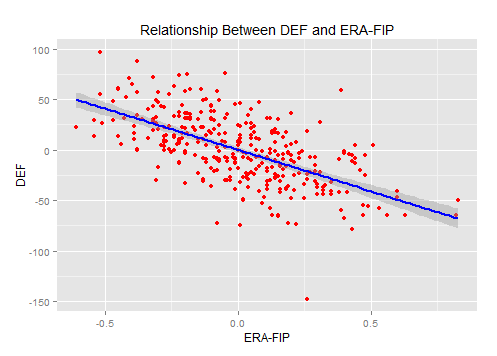

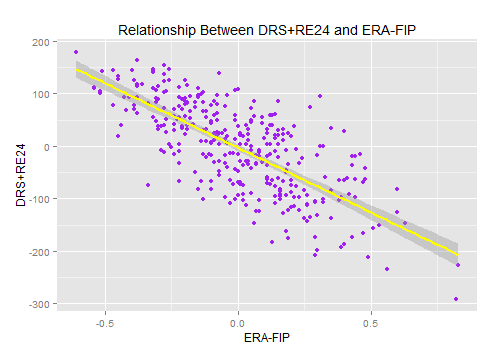

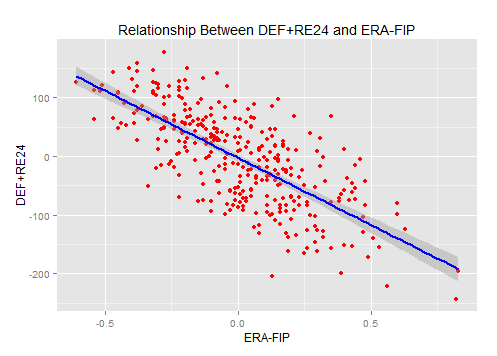

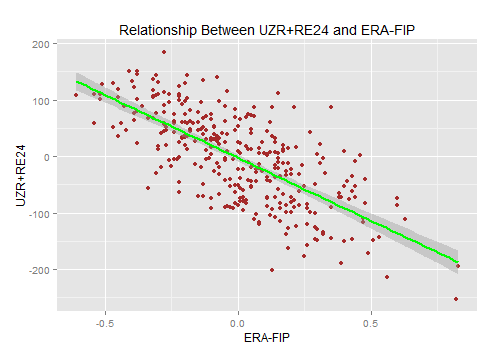

All the metrics have similar correlations, but DRS has the highest adjusted r-squared (correlation coefficient) value (.39), which measures how much of the variance in ERA-FIP is correlated by the defensive metric. FanGraphs’ DEF was right behind DRS (.37) and UZR had an adjusted correlation coefficient of (.34).

The result was somewhat surprising, because DRS and UZR do not factor in positional adjustments (UZR also does not measure catcher or pitcher defense). These metrics measure a player against the average player at that player’s position. They do not measure the difficulty of the position in comparison to other positions.

DEF does apply positional adjustments. FanGraphs uses UZR, not DRS, as the metric they apply the positional adjustments to in order to determine DEF. (see notes below for further explanation of positional adjustments)

Still, the non-positionally adjusted DRS correlates most closely to ERA-FIP. However, it does seem that the advantage over DEF is negligible.

All in all, defense, considered alone, appears to explain 35–40% of a team’s ERA-FIP.

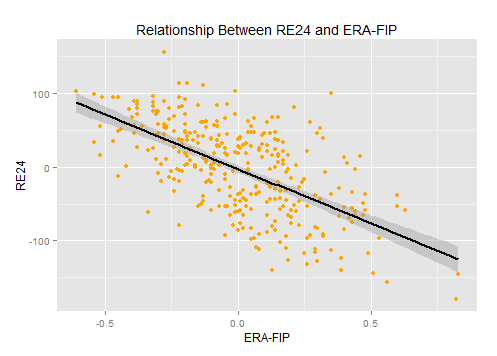

I chose to use a team’s Run Expectancy based on 24 base-out states (RE24) to measure the effects of sequencing. RE24 measures the change in run expectancy between the time a batter comes to the plate and the run expectancy after the plate appearance. The up and down of these changes will reflect the sequence of events experienced by each team (see notes below for further explanation of RE24).

The relationship between ERA-FIP and RE 24 has a similar correlation coefficient (.38) as ERA-FIP and the defensive metrics. Sequencing seems to play a role nearly equal to defense in determining the over- or under-performance of pitchers.

Again, DRS+RE24 (.54), DEF+RE24 (.53), and UZR+RE24 (.51) all yielded similar adjusted correlation coefficients.

This suggests roughly 50% of the difference between ERA and FIP are correlated to defense and sequencing. The other half of the difference is not the great unknown, but it’s (sort of) immeasurable.

The skill of the opponent in running the bases is probably a greater part of the other 50% than luck is. This was on display in the playoffs, whether it’s Lorenzo Cain scoring from first on a single, Daniel Murphy taking third base from first base on a walk, or one of the other examples of aggressive (and smart) baserunning witnessed throughout the playoffs. These events change run probabilities and create runs. These base running events tend to be less noticed during the 162-game season, but they still happen.

Some of the ability for catchers and pitchers to prevent stolen bases is cooked into the defensive metrics, but not much else is. FanGraphs’ Base Running (BsR) measures the baserunning abilities of players and teams, from an offensive perspective, but to my knowledge there is no accumulated stat to measure opponents’ BsR. The data is out there. The same measures used to determine BsR would only have to be aggregated from the perspective of the pitching team.

A measure of Opponents’ BsR would likely cover a good amount of the uncorrelated variance between ERA and FIP. There would still be a lot of luck left in play, but probably not as much as there is thought to be now.