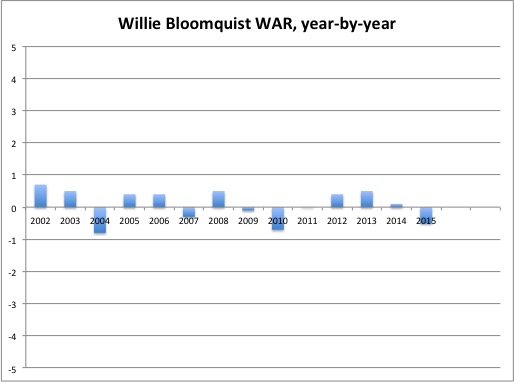

After 14 years in the Major Leagues, longtime utility player Willie Bloomquist was designated for assignment by the Mariners on Thursday. If this is truly the end, you have to agree that Willie Bloomquist had an amazing career when you stop to think about it. He lasted 14 years in the big leagues, played in over 1000 games, had more than 3000 plate appearances, and finished his career with a grand total of 1.0 WAR. As Tom Tango has pointed out many times, Willie Bloomquist has been “Mr. Replacement Level” for many years.

The highest WAR Willie B ever had in one season was 0.7 and that came in a 12-game stint as a September call-up in his rookie year of 2002. He hit .455/.526/.576 that year, thanks in large part to a sky-high .484 BABIP. In his last seven games that season, Bloomquist had a four-hit game, two three-hit games, and two two-hit games. He was the Fred Lynn of the 2002 Mariners (with apologies to Fred Lynn). Lynn had a sizzling 15-game stint in September of 1974 when he hit .419/.490/.698. Lynn, of course, followed up that torrid September with a terrific .331/.401/.566 year in 1975, winning the Rookie of the Year award and the AL MVP. Bloomquist followed up his scalding cup of coffee by hitting .250/.317/.321 over 89 games in 2003.

Imagine if Bloomquist never had that incredible BABIP-fueled 12-games stretch at the start of his career. How much did those 12 games affect the Mariners’ opinion of him, perhaps leading to more opportunities than a career-long replacement level player would normally get? Would he have had the career he had if not for that 12-games stretch of hot hitting?

It seemed destined for Willie Bloomquist to play for the Seattle Mariners. He was originally drafted out of nearby South Kitsap High School in Port Orchard, Washington in the eighth round of the 1996 amateur draft, but he eschewed the Mariners’ offer to go to Arizona State University. With the Sun Devils, he was named ASU On Deck Circle Most Valuable Player, just like Dustin Pedroia, Ike Davis, Paul Lo Duca, and Barry Bonds. That’s like a Mount Rushmore of Arizona State MVPs, plus Willie Bloomquist. At ASU, Bloomquist hit .394, the third-highest batting average in school history, and was the first Sun Devil to have back-to-back seasons with 100 or more hits. College Willie Bloomquist was pretty damn good.

After his junior season, Bloomquist was again drafted by the Mariners, this time in the third round. He signed and began his career with the Everett Aquasox in the Northwest League. He hit .287/.366/.410 that year while primarily playing second base. One of his teammates on the 1999 Aquasox was a 17-year-old Australian named Chris Snelling. Snelling was the youngest player on the team but hit .306/.388/.498 and looked to have a bright future. Unfortunately, he turned out to be the anti-Willie Bloomquist. Snelling was like a meteor that flashed quickly across the sky and disappeared after just 93 games in the big leagues across five injury-marred seasons. Willie Bloomquist was a slow and permanent planet who played 1055 games over 14 years at slightly above replacement level.

In 2000, Bloomquist was moved up to the High-A Lancaster JetHawks in the California League. This was a hitter’s league, with teams averaging 5.3 runs per game. Bloomquist had his best season, hitting .379/.456/.523 with 22 steals in 64 games, then was bumped all the way up from High-A to AAA. He was clearly overmatched and struggled mightily as a 22-year-old in AAA, hitting .225/.249/.277.

In 2001, while the Mariners were winning an amazing 116 games, Bloomquist was sent down to AA and hit .255/.294/.310, although with a career-best 34 steals. Despite his struggles hitting AA pitching, the Mariners aggressively moved Bloomquist up to AAA in 2002. He hit .270/.331/.383, then had that amazing 12-game stretch in September and the legend of Willie B was born.

Being able to play multiple positions was a big part of the baseball longevity of Willie Bloomquist. The only position other than pitcher that he never played was catcher. He never once donned the “Tools of Ignorance” but played at least 47 games at every other position, finishing his career with a negative UZR at every position he ever played. That’s consistency, my friends.

Bloomquist played the first seven years of his career with the Seattle Mariners, hitting .263/.322/.324 over that stretch, good for a .291 wOBA and 76 wRC+. He usually filled in at multiple positions, playing 80 to 90 games per year. He was like that bachelor uncle that always shows up at the family reunion but doesn’t do anything particularly memorable. Crazy aunt Alice will get into a heated argument with cousin Ashley over her too-revealing tank top, while ancient grandpa Ray loudly complains about whomever is currently occupying the White House, but uncle Willie just sits off to the side, casually eating some chips and drinking his beer. Everyone agrees he’s a good guy and nice to have around. If they need someone to man the grill for an hour, Willie’s the guy. If you’ve got a game of horseshoes going, or Bocce Ball or Cornhole or badminton or Frolf, Willie’s game. He never seems to win but isn’t the worst one out there either. He’s just a reliable guy, like mashed potatoes but without the gravy. Sure, you’d much rather have the gravy with the mashed potatoes but you’ll settle for just the spuds if there’s not a better option.

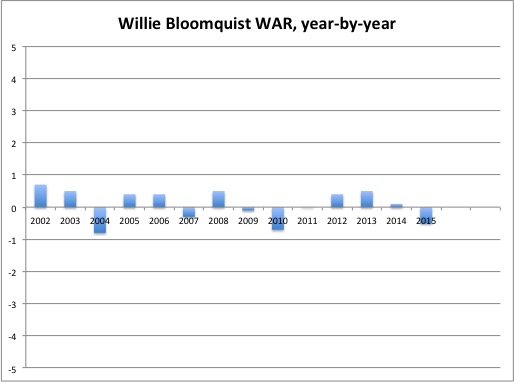

Bloomquist joined the Mariners at the tail end of their last real good stretch of baseball. From 1995 to 2001, the Mariners made the playoffs four times in seven years. Those remain their only four playoff appearances ever. Then Willie Bloomquist showed up in 2002 and they haven’t made the playoffs since (not that it’s his fault). From 2002 to 2008, Willie Bloomquist was reliably Willie Bloomquistian. He never had fewer than 1 WAR or more than 1 WAR in a season. This would hold true for his entire career:

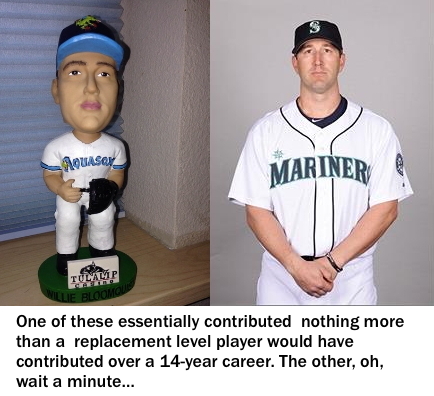

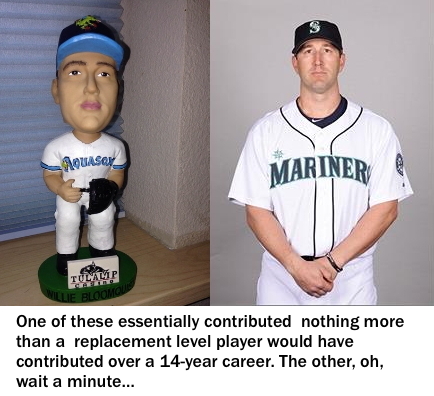

There’s that consistency again. Willie Bloomquist—reliably replacement level. Of course, minor league baseball promotions directors don’t care about WAR, so in 2004 the Everett Aquasox had Willie Bloomquist Bobblehead Doll Night. The resemblance is uncanny:

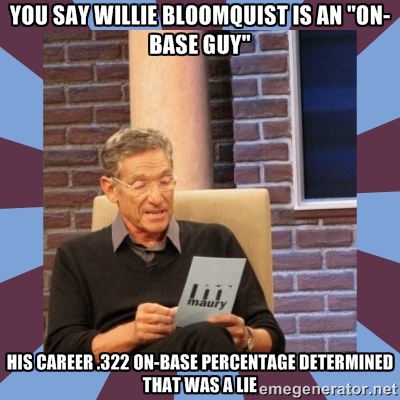

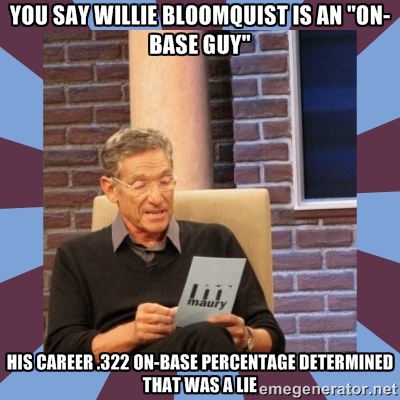

After the 2008 season, Willie B took his talents to Kansas City, signing a two-year, $3.1 million contract with the Royals as a free agent. Through six-plus years in the Major Leagues, Bloomquist had accumulated 1.4 WAR plus an unknown amount of intangibleness that likely added to his value. As Dayton Moore said at the time, “He’s an on-base guy, a speed-type player and a hustler. He’s a Craig Counsell-type player who really plays hard, hustles, and knows how to play.” If you were to bullet-point Moore’s statement, it would look like this:

- On-base guy

- Speed-type player

- Hustler

- Craig Counsell-type player

- Plays hard

- Hustles

- Knows how to play

That reads like the five paragraph essays I used to write in high school. I always wanted three examples but sometimes couldn’t think of three, so I would bust out the thesaurus and find synonyms (hustler, plays hard, hustles) so I could make the required word count. Bravo, Dayton Moore, bravo. Also, there’s this:

In his first year in Kansas City, Bloomquist played in a career-high 125 games, getting 468 plate appearances and hitting .265/.308/.355. He lived up to his “speed-guy” label by stealing a team-leading 25 bases. He was worth -0.1 WAR, almost exactly replacement-level, but WAR doesn’t measure intangibles, so we really don’t know his true value that year. He may have led the league in Hustle WAR and Knows How To Play WAR while likely finishing second to Craig Counsell in Craig Counsell WAR.

Other than the ample playing time, this 2009 season is the epitome of Willie Bloomquist. His triple-slash line, his walk rate, his strikeout rate, they were all very close to his career numbers. He also played every position except pitcher and catcher that year. Yep, in 2009 Willie Bloomquist was about as Willie Bloomquist as Willie Bloomquist could be.

His second year with the Royals did not go as well and he was sold to the Reds in September of 2010. I don’t know how much a 2010 Willie Bloomquist went for, but hopefully the Reds got a good deal.

In January of 2011, Willie Bloomquist got another free agent deal, this time signing with the Arizona Diamondbacks for one year. This was another quintessential Bloomquistian season. He played 97 games, had 381 plate appearances, and hit .266/.317/.340 (nearly a match for his .269/.316/.342 career batting line). He was worth 0.0 WAR.

This 2011 season was also the only season Willie got a taste of postseason play. In a five-game Division-Series loss to the Brewers, Bloomquist hit .318/.348/.318 with three steals. Yep, Willie Bloomquist has a career .318 average in the postseason, 10 points higher than Derek Jeter (yeah, I know there’s a difference of 153 games played. It’s not Willie’s fault he didn’t get the opportunities Jeter had. Don’t be a hater).

After Bloomquist’s 0.0 WAR season with the Diamondbacks, he re-signed with the team on a two-year, $3.8 million contract and had seasons worth 0.4 and 0.5 WAR. When Bloomquist’s contract expired after the 2013 season, the Diamondbacks didn’t look like they had room on the roster for Willie B, which led to this headline from the AZ Central: “Arizona Diamondbacks brace for departure of Willie Bloomquist.” I wonder how one braces for the departure of Willie Bloomquist? Does it involve eating chips and drinking beer?

According to the article, the Diamondbacks wanted Willie back for 2014, but the market for his services was moving quickly. “We like him a lot and would love to have him back,” Towers said. “But my sense is there are going to be some clubs after him aggressively early.” Hmm. A free-agent battle for a 36-year-old Willie Bloomquist. Well, I’ll be.

Apparently, the booming market for Willie Bloomquist resulted in the Seattle Mariners outfoxing their competition by signing Bloomquist to a two-year, $5.8 million deal. That’s not a bad chunk of change for “Mr. Replacement Level” (when the Moneyball-like film comes out about “Mr. Replacement Level”, Bloomquist will be played by Ben Foster, the Willie Bloomquist of Hollywood. If you don’t know who Ben Foster is, well, that’s why he’s the Willie Bloomquist of Hollywood).

Bloomquist was close to his typical self in his first season back with the Mariners, accounting for 0.1 WAR despite an ugly .297 OBP (and that was with a .356 BABIP). Once again, he was tabbed to fill in at every position on the diamond except for catcher and center field. He only stole one base, though, and had the lowest walk rate and highest strikeout rate of his career. It almost looked like age was catching up to Willie Bloomquist, but that could not possibly be true because Willie Bloomquist had seemingly not aged in more than a dozen years.

Sadly, it may be the end of The Willie Bloomquist Experience. His intangibles couldn’t make up for a .159/.194/.174 batting line and the Mariners have designated him for assignment. Maybe he will be picked up by another Major League team (or the Phillies) and he’ll bang out a .265/.315/.340 stretch one last time.

Despite his 14 years of ever-so-slightly-above replacement level play, I have to give credit to Willie Bloomquist. He played hard and he was willing to man most any position on the diamond. If you needed a bunt, Willie would bunt. In his early days, he could pinch-run and steal you a bag in a high-leverage situation. He must have been a great guy in the clubhouse to last as long as he did and he may not be done just yet. Jeff Francoeur hasn’t been above replacement level since 2011 and he’s still playing. As long as Francoeur continues to get work, there’s hope for Willie Bloomquist. If he isn’t signed by a Major League team (or the Phillies), he can be proud of what he accomplished in the big leagues.