Understanding Player Contracts from a Business Perspective

As statistics have become more advanced and public, we’ve gained myriad ways to understand baseball more in depth. We don’t just know that Aaron Judge smacks the crap out of the ball; we know that he can hit it out of the park at more than 120 miles per hour. We don’t just know that Yu Darvish’s pitches can dive all over the zone, but that they have an average spin rate of more than 2500 revolutions per minute.

While those stats represent single facets of a player’s game, there’s one that incorporates everything they do to give a sense of their overall value: Wins Above Replacement, or WAR. Depending where you find your stats — there’s fWAR from FanGraphs or bWAR from Baseball Reference — there will be subtle differences in how it’s calculated. But the point is the same: to tell you who the best and worst players are compared to anyone who could replace them.

WAR is the type of stat that enables us to react in real time, and with relatively sound reason, to newly-signed contracts. It’s how we can say Kevin Kiermaier’s deal is probably a notable win for the Rays and why Ryan Howard’s last extension was premature at best.

The reality we shape as observers and fans often looks at these contracts under a microscope, and only under a microscope. When a guy strikes out looking to end a rally, or gives up the hit that sparks one, that’s when we notice. And, fair or not, those moments craft the narratives we often carry throughout the life of a player’s contract.

Zooming out is helpful, though. In certain context, there might not be such a thing as a bad contract.

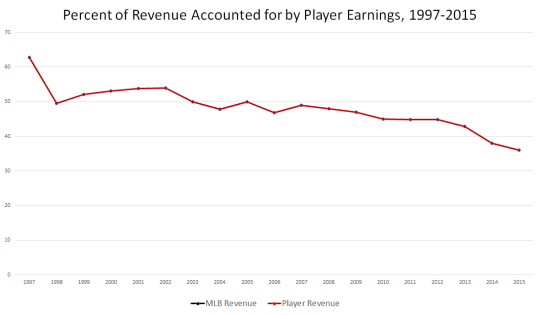

Owners have been raking in the money for a long, long time. They’ve pretty much always taken home more than the players and in recent years that difference has only grown. When you consider that there are only ever as many owners as there are teams, and that the players’ share is split hundreds more times, the disparity becomes emphasized.

If we want additional perspective, we can look at how the percent of overall revenue accounted for by player salaries has decreased almost annually like clockwork.

Revenue data goes beyond that which fans and analysts use to justify a point of view on a player’s worth to their team. Those trains of thought spur additional conversation about how a given contract can influence the team’s composition and ability to compete for championships. And these points may well hold water. But they probably don’t provide much influence on the business perspective.

No matter how good or bad a contract is, a team is likely still profitable and operating within a relatively certain margin of error that isn’t dramatically different than if they didn’t have that deal on the books.

That’s not to say owners don’t care about a bad contract. It’s just that, at an operational level, they have to concern themselves with the bottom line first and foremost because it’s what allows them to persist. Sure, the big deals that go sour are disappointing to them, but they’re not damning.

Tim Jackson is a writer and educator who loves pitching duels. Find him and all his baseball thoughts online at timjacksonwrites.com/baseball and @TimCertain.