Hardball Retrospective – What Might Have Been – The “Original” 2008 Mariners

In “Hardball Retrospective: Evaluating Scouting and Development Outcomes for the Modern-Era Franchises”, I placed every ballplayer in the modern era (from 1901-present) on their original team. I calculated revised standings for every season based entirely on the performance of each team’s “original” players. I discuss every team’s “original” players and seasons at length along with organizational performance with respect to the Amateur Draft (or First-Year Player Draft), amateur free agent signings and other methods of player acquisition. Season standings, WAR and Win Shares totals for the “original” teams are compared against the “actual” team results to assess each franchise’s scouting, development and general management skills.

Expanding on my research for the book, the following series of articles will reveal the teams with the biggest single-season difference in the WAR and Win Shares for the “Original” vs. “Actual” rosters for every Major League organization. “Hardball Retrospective” is available in digital format on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, GooglePlay, iTunes and KoboBooks. The paperback edition is available on Amazon, Barnes and Noble and CreateSpace. Supplemental Statistics, Charts and Graphs along with a discussion forum are offered at TuataraSoftware.com.

Don Daglow (Intellivision World Series Major League Baseball, Earl Weaver Baseball, Tony LaRussa Baseball) contributed the foreword for Hardball Retrospective. The foreword and preview of my book are accessible here.

Terminology

OWAR – Wins Above Replacement for players on “original” teams

OWS – Win Shares for players on “original” teams

OPW% – Pythagorean Won-Loss record for the “original” teams

AWAR – Wins Above Replacement for players on “actual” teams

AWS – Win Shares for players on “actual” teams

APW% – Pythagorean Won-Loss record for the “actual” teams

Assessment

The 2008 Seattle Mariners

OWAR: 41.0 OWS: 251 OPW%: .519 (84-78)

AWAR: 21.3 AWS: 183 APW%: .377 (61-101)

WARdiff: 19.7 WSdiff: 68

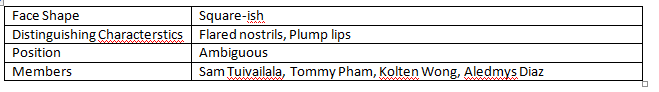

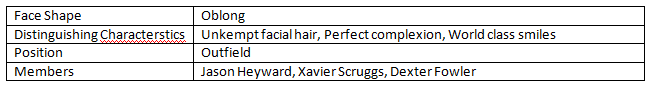

The “Original” 2008 Mariners finished a few percentage points behind the Athletics for the AL West crown but out-gunned the “Actual” M’s by a 23-game margin. Alex Rodriguez (.302/35/103) paced the Junior Circuit with a .573 SLG. Raul Ibanez (.293/23/110) established career-highs with 186 base hits and 43 two-base knocks. Ichiro Suzuki nabbed 43 bags in 47 attempts and batted .310, topping the League with 213 safeties. Jose Lopez socked 41 doubles and 17 long balls while posting personal-bests with 191 hits and a .297 BA. Adrian Beltre clubbed 25 four-baggers and earned his second Gold Glove Award for the “Actuals”.

Ken Griffey Jr. ranked seventh in the center field charts according to “The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract” top 100 player rankings. “Original” Mariners chronicled in the “NBJHBA” top 100 ratings include Alex Rodriguez (17th-SS) and Omar Vizquel (61st-SS).

Original 2008 Mariners Actual 2008 Mariners

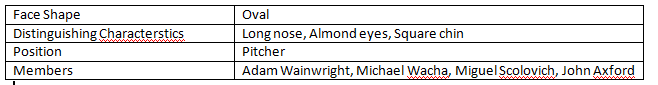

| STARTING LINEUP | POS | OWAR | OWS | STARTING LINEUP | POS | AWAR | AWS |

| Raul Ibanez | LF | 1.77 | 19.64 | Raul Ibanez | LF | 1.77 | 19.64 |

| Ichiro Suzuki | CF/RF | 3.36 | 19.48 | Jeremy Reed | CF | -0.18 | 4.19 |

| Shin-Soo Choo | RF | 2.86 | 14.97 | Ichiro Suzuki | RF | 3.36 | 19.48 |

| Ken Griffey, Jr. | DH/RF | 0 | 13.1 | Jose Vidro | DH | -1.34 | 1.53 |

| Bryan LaHair | 1B | -0.42 | 1.66 | Richie Sexson | 1B | 0.06 | 4.43 |

| Jose Lopez | 2B | 2.73 | 18.55 | Jose Lopez | 2B | 2.73 | 18.55 |

| Asdrubal Cabrera | SS/2B | 1.85 | 11.92 | Yuniesky Betancourt | SS | 0.2 | 8.69 |

| Alex Rodriguez | 3B | 4.99 | 27.21 | Adrian Beltre | 3B | 2.45 | 16.09 |

| Jason Varitek | C | 0.7 | 8.74 | Kenji Johjima | C | -0.01 | 6.1 |

| BENCH | POS | AWAR | AWS | BENCH | POS | AWAR | AWS |

| David Ortiz | DH | 1.37 | 12.01 | Willie Bloomquist | CF | 0.15 | 3.92 |

| Ramon Vazquez | 3B | 1.05 | 9.63 | Miguel Cairo | 1B | -0.64 | 3.17 |

| Adam Jones | CF | 1 | 9.12 | Jeff Clement | C | -0.36 | 2.88 |

| Yuniesky Betancourt | SS | 0.2 | 8.69 | Jamie Burke | C | -0.16 | 1.89 |

| Greg Dobbs | 3B | 0.7 | 7.22 | Bryan LaHair | 1B | -0.42 | 1.66 |

| Kenji Johjima | C | -0.01 | 6.1 | Luis Valbuena | 2B | 0.15 | 1.19 |

| Omar Vizquel | SS | -0.22 | 3.94 | Wladimir Balentien | RF | -1.18 | 1.09 |

| Willie Bloomquist | CF | 0.15 | 3.92 | Greg Norton | DH | 0.21 | 0.99 |

| Jeff Clement | C | -0.36 | 2.88 | Brad Wilkerson | RF | -0.13 | 0.6 |

| Luis Valbuena | 2B | 0.15 | 1.19 | Rob Johnson | C | -0.3 | 0.35 |

| Wladimir Balentien | RF | -1.18 | 1.09 | Matt Tuiasosopo | 3B | -0.28 | 0.32 |

| Chris Snelling | – | 0.16 | 0.58 | Mike Morse | RF | 0.03 | 0.28 |

| Rob Johnson | C | -0.3 | 0.35 | Tug Hulett | DH | -0.2 | 0.16 |

| T. J. Bohn | LF | 0.05 | 0.34 | Charlton Jimerson | LF | -0.03 | 0 |

| Matt Tuiasosopo | 3B | -0.28 | 0.32 | ||||

| Jose L. Cruz | LF | -0.34 | 0.17 |

Derek Lowe and Gil Meche compiled identical records (14-11) while starting 34 games apiece. “King” Felix Hernandez contributed nine victories with an ERA of 3.45 in his third full season in the Major Leagues. Brian Fuentes accrued 30 saves while fashioning an ERA of 2.73 along with a 1.101 WHIP. “T-Rex” whiffed 82 batsmen in 62.2 innings pitched.

Original 2008 Mariners Actual 2008 Mariners

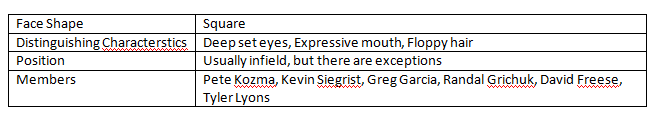

| ROTATION | POS | OWAR | OWS | ROTATION | POS | AWAR | AWS |

| Derek Lowe | SP | 4.16 | 15.69 | Felix Hernandez | SP | 3.99 | 13.45 |

| Gil Meche | SP | 3.7 | 13.81 | Ryan Rowland-Smith | SP | 2.1 | 8.39 |

| Felix Hernandez | SP | 3.99 | 13.45 | Erik Bedard | SP | 1.24 | 5.4 |

| Ryan Rowland-Smith | SP | 2.1 | 8.39 | Jarrod Washburn | SP | 0.7 | 5.11 |

| Joel Pineiro | SP | -0.39 | 3.75 | R. A. Dickey | SP | 0.2 | 3.28 |

| BULLPEN | POS | OWAR | OWS | BULLPEN | POS | OWAR | OWS |

| Brian Fuentes | RP | 1.88 | 11.8 | Brandon Morrow | SW | 1.09 | 7.19 |

| Matt Thornton | RP | 1.95 | 9.41 | Roy Corcoran | RP | 0.71 | 6.7 |

| Ryan Franklin | RP | 0.52 | 7.47 | J. J. Putz | RP | 0.4 | 5.24 |

| Brandon Morrow | SW | 1.09 | 7.19 | Sean Green | RP | -0.56 | 3.59 |

| George Sherrill | RP | 0.03 | 6.43 | Arthur Rhodes | RP | 0.48 | 3.03 |

| Aquilino Lopez | RP | 0.93 | 6.13 | Cesar Jimenez | RP | 0.66 | 2.28 |

| Damaso Marte | RP | 0.52 | 6.02 | Randy Messenger | RP | 0.19 | 0.84 |

| J. J. Putz | RP | 0.4 | 5.24 | Mark Lowe | RP | -1.11 | 0.68 |

| Cha-Seung Baek | SP | 0.56 | 3.67 | Cha-Seung Baek | SW | -0.11 | 0.56 |

| Mike Hampton | SP | 0.34 | 2.32 | Jake Woods | RP | -0.3 | 0.05 |

| Cesar Jimenez | RP | 0.66 | 2.28 | Miguel Batista | SP | -1.89 | 0 |

| Ron Villone | RP | -0.13 | 1.94 | Ryan Feierabend | SP | -0.88 | 0 |

| Rafael Soriano | RP | 0.28 | 1.78 | Eric O’Flaherty | RP | -1.07 | 0 |

| Shawn Estes | SP | 0.03 | 0.88 | Carlos Silva | SP | -1.91 | 0 |

| Mark Lowe | RP | -1.11 | 0.68 | Justin Thomas | RP | -0.07 | 0 |

| Scott Patterson | RP | 0.22 | 0.43 | Jared Wells | RP | -0.31 | 0 |

| Kameron Mickolio | RP | -0.09 | 0.08 | ||||

| Ryan Feierabend | SP | -0.88 | 0 | ||||

| Eric O’Flaherty | RP | -1.07 | 0 | ||||

| Justin Thomas | RP | -0.07 | 0 |

Notable Transactions

Alex Rodriguez

October 30, 2000: Granted Free Agency.

January 26, 2001: Signed as a Free Agent with the Texas Rangers.

February 16, 2004: Traded by the Texas Rangers with cash to the New York Yankees for a player to be named later and Alfonso Soriano. The New York Yankees sent Joaquin Arias (April 23, 2004) to the Texas Rangers to complete the trade.

October 29, 2007: Granted Free Agency.

December 13, 2007: Signed as a Free Agent with the New York Yankees.

Derek Lowe

July 31, 1997: Traded by the Seattle Mariners with Jason Varitek to the Boston Red Sox for Heathcliff Slocumb.

November 1, 2004: Granted Free Agency.

January 11, 2005: Signed as a Free Agent with the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Shin-Soo Choo

July 26, 2006: Traded by the Seattle Mariners with a player to be named later to the Cleveland Indians for Ben Broussard and cash. The Seattle Mariners sent Shawn Nottingham (minors) (August 24, 2006) to the Cleveland Indians to complete the trade.

Gil Meche

October 31, 2006: Granted Free Agency.

December 13, 2006: Signed as a Free Agent with the Kansas City Royals.

Ken Griffey Jr.

February 10, 2000: Traded by the Seattle Mariners to the Cincinnati Reds for Jake Meyer (minors), Mike Cameron, Antonio Perez and Brett Tomko.

David Ortiz

September 13, 1996: the Seattle Mariners sent David Ortiz to the Minnesota Twins to complete an earlier deal made on August 29, 1996. August 29, 1996: The Seattle Mariners sent a player to be named later to the Minnesota Twins for Dave Hollins.

December 16, 2002: Released by the Minnesota Twins.

January 22, 2003: Signed as a Free Agent with the Boston Red Sox.

Honorable Mention

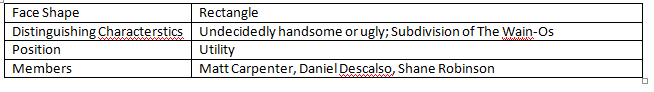

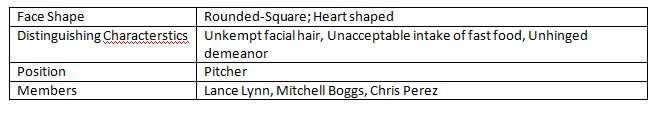

The 1999 Seattle Mariners

OWAR: 46.4 OWS: 296 OPW%: .549 (89-73)

AWAR: 33.8 AWS: 237 APW%: .488 (79-83)

WARdiff: 12.6 WSdiff: 59

The “Original” 1999 Mariners secured the American League Western Division title by six games over the Rangers. The “Actuals” placed third, sixteen games behind Texas. Ken Griffey Jr. (.285/48/134) paced the circuit in home runs, tallied 123 runs and collected his tenth Gold Glove Award. Edgar Martinez (.337/24/86) topped the League with a .447 OBP. Alex Rodriguez (.285/42/111) swiped 21 bags and scored 110 runs. Slick-fielding shortstop Omar Vizquel posted career-highs in batting average (.333), runs scored (112) and base hits (191) while stealing successfully on 42 of 51 attempts. Tino Martinez clubbed 28 four-baggers and plated 105 baserunners. Bret Boone tagged 38 doubles and surpassed the century mark in runs. Jason Varitek drilled 39 two-base knocks and swatted 20 big-flies during his first full campaign.

Mike Hampton (22-4, 2.90) placed runner-up in the Cy Young Award balloting. Derek Lowe notched 15 saves in 74 relief appearances. Dave Burba contributed a 15-9 record and set personal-bests with 34 starts and 220 innings pitched.

On Deck

What Might Have Been – The “Original” 1993 Angels

References and Resources

Baseball America – Executive Database

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York, NY.: The Free Press, 2001. Print.

James, Bill, with Jim Henzler. Win Shares. Morton Grove, Ill.: STATS, 2002. Print.

Retrosheet – Transactions Database

The information used here was obtained free of charge from and is copyrighted by Retrosheet. Interested parties may contact Retrosheet at “www.retrosheet.org”.