A Pure Measure of Fielding Ability: Predictive Ultimate Zone Rating

Throughout the pre-sabermetric revolution days of baseball, the statistics that determine fielding ability (namely errors and fielding percentage) had generated much criticism of fielding stats and undeserving gold glove award winners (Derek Jeter et al), and had kept fielding ability a mystery. However, this mystery in part led to the sabermetric revolution in baseball statistics. In the current day and age, with improved measures of performance available publicly, measuring fielding ability is somewhat less of an enigma, but still far from perfect.

One of the most often used fielding metrics in this day and age is UZR or Ultimate Zone Rating (click the link for an excellent FanGraphs explanation). Instead of counting perceived plays and errors, UZR records every batted ball hit to each of the numerous zones on the baseball field at each trajectory and the runs lost/saved as the fielder gets to the ball or falls short. This is found by matching the average result of the play with the Run Expectancy Matrix. Therefore, UZR provides a very accurate measure of how valuable that fielder was in terms of runs saved/lost over the course of the season.

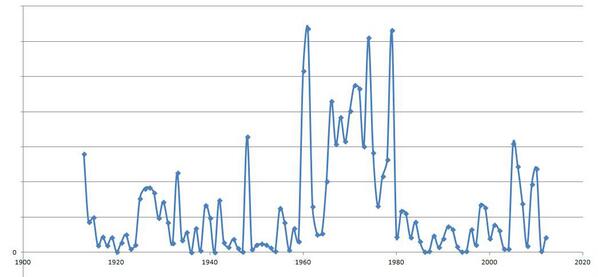

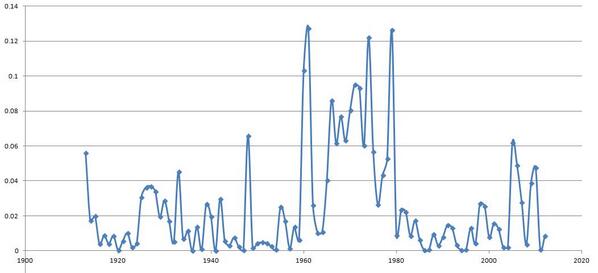

However, there are major problems with UZR. Sample size issues cause large fluctuations from month to month and even year to year. Moreover, it does not provide a stable basis of fielding ability. Even when all players’ impacts are averaged to a constant, UZR/150, averaged to runs saved/lost per 150 defensive games, the metric is very volatile.

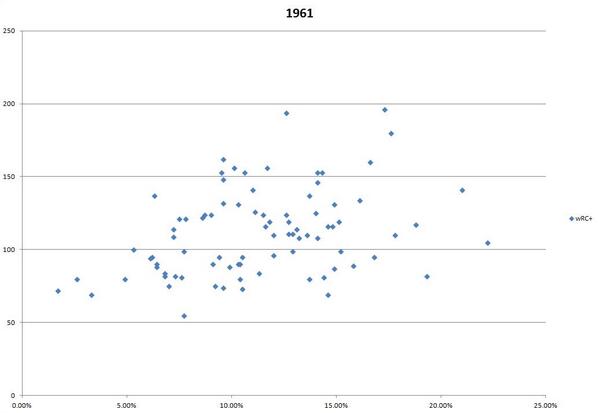

The reasons behind this might actually be easier to identify and correct than you might think. Let’s face it: not all fielders get the same amount of balls hit to them in the same place at the same trajectory within the same number of outs or innings. Infielders with a good knuckleballer on the mound and a slap hitter at the plate are going to get more grounders to each zone than infielders whose teams have fly ball pitchers on the mound and face lots of power hitters at the plate.

However, while the actual amounts may fluctuate from pitcher to pitcher and hitter to hitter, many fielders get a decent sample size of each batted ball to each zone over the course of multiple seasons. Even with a staff of fly ball pitchers, infielders will still handle their fair share of ground balls to each zone over the course of a season. So if there was a way to average all the pitchers and hitters together and measure the value and frequency of making a play in each zone based on the entire AL, NL, or MLB* average batted ball chart, then we could create a similar metric that would be more predictive, rather than purely descriptive.

*The purpose of separating the leagues is the discrepancy of hitting ability with the DH in the AL and the increased frequency of bunts (from pitchers) in the NL.

If we take the average percentage of batted balls to each zone with each trajectory for the AL, NL, or MLB and multiply that by the average runs saved/lost for plays made or missed in that zone, we can find a universal batted ball sample from which to apply the fielders’ impact. While this would not be directly proportional to the runs saved/lost for the fielder during that season for that pitching staff and the batters faced, it would be a metric independent of the impact that the pitcher and hitter has on the fielders. It would measure pure fielding ability over multiple seasons in the form of runs saved, but unbiased by the specific ratio of batted balls per zone and trajectory hit to the fielder over the seasons.

Predictive UZR will have sample size issues but when taken over multiple seasons, a starting fielder should get his fair share of batted balls hit to each zone with each trajectory. The percentages for his success rates at each zone and trajectory can then be applied not to the actual ratio of batted balls per zone hit his way (from his team’s pitching staff and hitters faced) but rather the average ratio of batted balls per zone hit in the entire AL, NL, or MLB.

Both UZR and Predictive UZR are very valuable for different things. UZR is a good reflection of the fielder’s direct impact on defense for the season. However, this might not accurately reflect the fielder’s true talent level because of the assortment of batted balls hit his way. Predictive UZR, while not a concrete reflection of the past runs saved, is a more pure measure of fielding ability. It can provide a number that, when compared to UZR, tells which fielder got lucky and which fielder did not, based on his pitching staff and the hitters faced. Another interesting twist the concept of Predictive UZR brings is that it can be based on the average batted ball chart of teams, divisions, and differing pitching staffs in addition to the AL, NL, or MLB. So a fielder’s projected direct impact, or UZR, can be transferred more easily as he moves from team to team, forming the basis of more accurate fielding projections.

Predictive UZR is not by any means a substitute to UZR, but rather complements it and works with it in intriguing ways. It is a concept worth looking into that has the potential to leave fans, media and front office personnel better informed about the game of baseball.

Nik Oza

Georgetown Class of 2016

Follow GSABR on twitter: @GtownSports