Don Mattingly’s Dodgers In the Context of wOBA Expected Runs

Weighted On-Base Percentage (wOBA) is typically considered to be the best measure of offensive ability and effect on runs scored among other rate statistics such as batting average, slugging percentage, and on-base percentage. 89.8% of a team’s runs scored correlates to wOBA between 2005–2015. I decided to look at a team’s performance, measured by how many runs they scored in a season, against the amount of runs wOBA predicted* they would have scored. (wOBA Expected Runs was calculated based on a linear regression model with runs modeled as wOBA. The adjusted r-squared value of R~wOBA is .898)

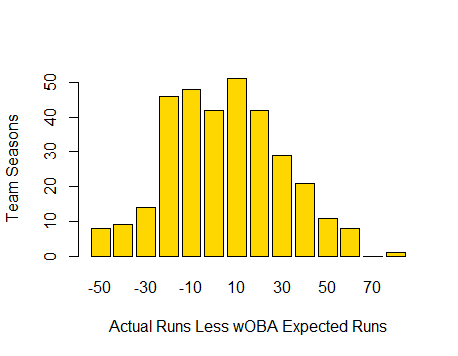

Generally, the results are what you would expect. Teams deviate from their wOBA Expected Runs, but the 50% of the teams (between the 25th and 75th percentile of the observations) range between -17.49 and 16.9 runs from their wOBA Expected Runs.

The outliers even fall within the uncorrelated portion of the relationship between runs scored and wOBA. As stated above, wOBA explains 89.8% of runs between 2005 and 2015. At the far right of the graph is the 2008 Minnesota Twins, who scored 829 runs against their 756 wOBA Expected Runs. The difference, 73 runs, is less than the 10% of runs that is theoretically not explained by wOBA. At the far left of the graph is the 2005 Arizona Diamondbacks who scored 696 runs against their expected amount of 756. Again, this 60-run differential falls within the 10% gap we would expect.

The mean difference of runs scored from the wOBA Expected Runs Scored is minuscule (.003 runs) and the standard deviation from that mean is 24.9 runs. This all strengthens wOBA’s position as the best offensive run predictor.

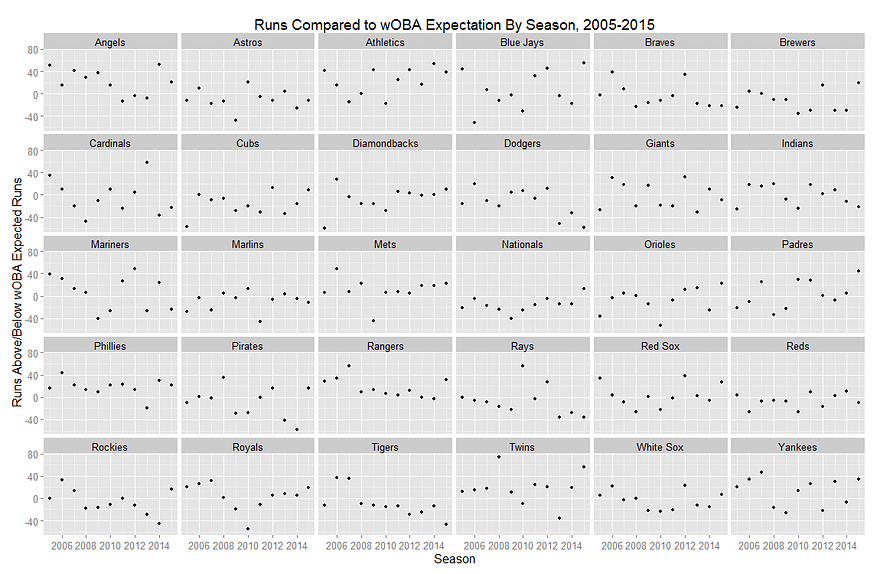

What does this all have to do with Don Mattingly and the Dodgers? The graphs below show each team’s runs scored below or above their wOBA Expected Runs Scored. You’ll see that teams fall within the standard deviation of runs scored less wOBA Expected Runs (-25.93–24.87), with some exceptions. The exceptions that fall outside of that range generally do not display a tendency for extreme over- or under-performance of their wOBA Expected Runs in consecutive seasons; however one team does stand out.

The 2013–2015 Dodgers consistently under-performed their wOBA Expected Runs, with the following differences in the respective seasons from 2013–2015: -51, -33, and -58 runs. To put this in context, only 8 of 330 of teams, or roughly 2%, that took the field between 2005–2015 under-performed their wOBA Expected Runs by more than two standard deviations (-49.8). The 2013 and 2015 Los Angeles Dodgers were two of those teams. No other franchise appears on the list twice, much less twice within three seasons.

In Mattingly’s first two seasons with the Dodgers (2011 and 2012) the results were standard, with a -6 and +12 runs to wOBA Expected Runs differential, but when the Dodgers came under new ownership and started spending to bring in new players things changed. The team got better but their performance in relation to what they were doing got worse.

A glance at the graphs above will show that teams have under-performed their expectations, but never this badly for a three-year stretch. There is luck and there are trends, and the Dodgers are a trend of under-performance. Does this mean Don Mattingly is a bad manager? Maybe. Does it mean that Mattingly was a bad fit for this Dodgers team as constructed? Probably.

It could all be on the hitters; it could all be bad luck, but those seem unlikely. The 2013–2015 Dodgers are the worst offensive under-achievers in the last decade. The results suggest that Mattingly was unable to shuffle a cast of talented and enigmatic hitters into the right order to produce the best sequencing of results. Alternatively, the other narrative is that Mattingly was handed a group of talented and enigmatic hitters that couldn’t execute situational hitting and hit inconsistently. Either way, the Dodgers cost themselves a lot of wins through one, or a combination of the two narratives. The team lost 5, 3, and 5 wins each year, compared to if they met their wOBA Expected Runs, as calculated using the Runs per Win for 2013–2015.

This doesn’t necessarily bode poorly for Mattingly in Miami. The Marlins don’t have the benefit of a deep and talented bench. They are a fairly straight-forward offensive team that should allow Mattingly to write-up consistent lineups so long as the team remains healthy. This is not to say the Marlins will out-perform the Dodgers. It is to say that the Marlins may perform closer to how we would expect them to perform.

However, if the problem did not lie with Mattingly, but instead the Dodgers’ roster, than things do bode poorly for the Dodgers. It will be interesting to see if Dave Roberts can unlock something Mattingly could not; or whether the players are to blame; or whether Los Angeles must wait for Gabe Kapler, baseball’s philosopher-king, to set the runs free.

You can read more of my thoughts, opinions, and research on baseball at https://medium.com/simply-bases. Twitter: @simplybases.

wOBA doesn’t take baserunning into account, IIRC, the dodgers haven’t been very good at it.

I actually looked at performance just based on weights for all hits and stolen bases and caught stealing and the results weren’t much different. I think it may exacerbate the difference.

I tend to believe it’s more due to lineup construction. For example, Joc Pederson would have been expected to produce 53-54 runs through his 26 HRs last season, based upon linear weights. However, those HRs only produced 34 runs.

Baserunning may explain part of it, but I believe a larger part is explained by poor timing based on where players were put in the lineup.