Old Player Premium

One of Dave Cameron’s articles a while back showed payroll allocations by age groups, and it shows that over the last five years or so more money is going to players in their prime years while less is being spent on players over 30. That seems to be a logical thing for teams to do, but that trend can only continue for so long. Eventually a point will be reached where older players are undervalued, and it might be possible that we are already there.

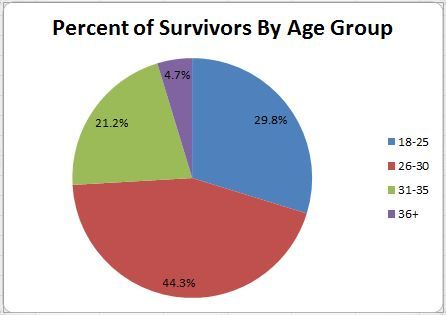

There are several things to keep in mind when comparing these age groups, and one of the biggest is the survivorship bias. There is a natural attrition over time for players in general. Let’s look at an example, and for all the following I will be using 2012 versus 2013 as a way to see what happens from year to year. To look at survivorship, I looked at all position players in 2012 and then their contribution in 2013 to see how many disappeared the next year. The players that were not in the 2013 year could be due to retirement, demotion, injury, etc. I also took out a small group that played in both seasons, but were basically non-factors in 2013, for example Wilson Betemit played in both seasons, but in 2013 he only had 10 plate appearances. The attrition rate for the age groups looks like this:

| Age Group | % of 2012 Players That Did Not Contribute in 2013 |

| 18-25 | 22.2% |

| 26-30 | 25% |

| 31-35 | 29.3% |

| 36+ | 38.9% |

As you would expect, the attrition rate increases over time. Players in their late teens and early 20s who make it to the majors are likely to be given opportunities in the near future, but as the age increases the probability of teams giving up on the player, major injury, or retirement goes up. Players who make it from one group to the next have survived, and that is where the bias comes in. By the time you get to the 36+ group a significant number of the players are really good because if they weren’t they would not have made it so far. This ability to survive is also a reason why they should be getting a good chunk of the payroll. As I will show you, it leads to steady play which teams should pay a premium for.

The next step is looking at performance risk among the groups. To look at this I took each group’s performance in 2012 and compared it to the group’s performance in 2013, again only with survivors from year to year. I looked at both wRC+ and WAR just to see if only the hitting component or overall performance behaved differently.

Further, to calculate a risk level I looked at the standard deviations of the differences (2013 minus 2012) for each player, but those are not directly comparable. Standard deviation is higher for distributions with higher averages due to scaling issues. For instance, the average 36+ player had a 95 wRC+ in 2012 versus, which is more than 10 wRC+ above the average 18 to 25 year old in the same year. A 10% drop or increase in production is therefore a larger absolute change for the 36+ player, so they naturally end up with a higher standard deviation. To take care of this I calculated the standard deviation of the difference as a % of 2012 average production as the overall riskiness measure.

| Age Group | wRC+ Risk | WAR Risk |

| 18-25 | 56.5% | 167.7% |

| 26-30 | 48.3% | 118.9% |

| 31-35 | 46.4% | 140.7% |

| 36+ | 35.2% | 92.8% |

Don’t compare the wRC+ to WAR figures as there are again scaling issues, but look at the age groups. A one standard deviation change is most volatile for the youngest age group, so the younger players are the most uncertain or most risky. That is what we would expect as we have all seen prospects flame out. The middle two groups are similarly volatile with the 31 to 35 group have a slightly lower risk level in the hitting for this sample and slightly higher overall play according to the WAR risk. More years might need to be compared to see how consistent those groups are relatively. The 36+ players are significantly less risky than the other ages. If they decline by 1 standard deviation it will mean a smaller reduction in performance, less volatile and less risky.

The only thing that really hurts the older players is the aging curve. They are more likely to see a decline in performance. From the youngest group to oldest the percent of players who were worse in 2013 than they were in 2012 by wRC+ was 52.3%, 54.5%, 64.4%, 63.6%, and for WAR 52.9%, 48.7%, 56.7%, and 81.8%. So it is more likely that the older players will see performance worse than the previous year, but again a drop for them will likely be smaller due to lower volatility and it is on average from a higher level of performance to begin with.

Older players are like buying bonds for your investment portfolio, you have a pretty good idea of what there going to pay in the next period with occasional defaults. Younger players are more like growth stocks, you aren’t sure when or if they are going to pay dividends but when they do you can make huge returns. Investors pay a premium for bonds (accept a lower rate of return) due to their stability, and teams pay more for older players than maybe their production seems to warrant for the same reason.

If you go back to the payroll allocation, part of the shift is in the number of players in each group. The 31-35 year-olds no longer get the largest chunk of payroll in part because there are more 26 to 30 year-old players. Baseball is getting younger overall, so a larger portion of the money going to younger players is inevitable. The 18 to 25 group isn’t getting a large change in payroll allocation because they are generally under team control, but the teams are extending the players at that age with the money showing up as they get into the next couple age groups. Like Chris Sale, who is making $3.5 million this year on the extension he signed (he’s 25), but when he is 26, 27, and 28 he will make 6, 9.15, and 12 million respectively.

So the 36+ group, as you can see only 4.7% of the players, used to make about 20% of the total salaries paid, but now they make 15 or 16% (I don’t have Dave’s exact numbers). Is that premium fair, four times more of the allocation than they make up of the overall player pool? That is a tough question, and one I am working on. If anyone can give me tips on how to dump lots of player game logs, that is probably what I am going to do next, but haven’t figured out how to do it without eating up my entire life. Being more certain on this sort of thing, and having a relative risk measure for players could make contracts a lot easier to understand and predict.