“Make baseball fun again” is Bryce Harper‘s outcry against baseball fundamentalists who continue to police emotions and enforce baseball’s expressionless professionalism. “Shut up and play the game right” might be something you’d hear uttered from the fundamentalist’s side — ideally through tobacco-glazed teeth — and maybe by Brian McCann. The discourse is of course more involved than that, covering everything from retaliatory plunk balls to bat flips, and anytime something marginally inflammatory happens, it’s beaten so hard that we’re reminded how boring our lives are that we have to discuss the same things over and over and over. I know you can picture the media package that accompanies the discourse: a young, brash, exquisitely coiffed, generational talent, who was hit in the ribs in his first ever plate appearance (then proceeded to steal home), is unabashedly passionate about a “fun” revolution in baseball. His eye black is adorned like war paint; he has emojis on the bottom of his bats; his helmet never stays on his head when he runs the bases; and yes, he “pimps” his home runs. Cut to Joey Bats‘ ALDS bat flip and the ensuing brawl and then connect it with Rougned Odor’s haymaker; cut to Brian McCann standing at home plate waiting for Jose Fernandez after his first career home run; then enter the commentator: “Is this wrong?”

While baseball’s moral code on gaining an edge is unpredictable, there’s always been the idea that individuals conform to the game, not the other way around. Harper’s sermon won’t shatter the code of conduct, but it might move the needle, if it hasn’t already. For example, I can’t think of a standout incident this season because of a bat flip. That’s good! Because bat flips are really fun! There’s really no need to overthink it. There were plenty of memorable bat flips this year, and in an effort to make some fun out of baseball when there is no baseball being played, I’m breaking out my bat flip tracking equipment (a ruler, a stop watch, and a parabolic trajectory calculator) that I introduced last year, and booting up BatCast for a look back at the year’s most memorable wood-chucking moments.

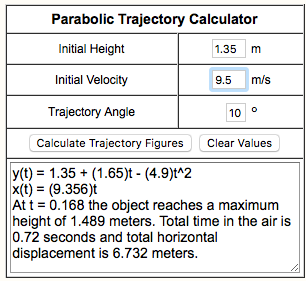

A brief recap: arriving at these numbers is a sloppy and wildly imprecise affair. I pull videos, gifs, and stills of a bat flip and start by measuring the height of the player as he appears on my screen. I convert that measurement into the player’s real-life size and reference this ratio, as well as measurements on the baseball field, and rough estimates, to arrive at some of the data I present to you in meters and feet: initial height, apex, and distance. Using a stopwatch or the time stamp on YouTube, I can declare a fairly accurate hang time of the bat. Angles are roughly noted using the batter and the ground to form a 90-degree angle and are adjusted in the parabolic trajectory calculator.

Let’s kick this off:

Exhibit A – The one that’s probably at the forefront of your mind:

|

Asdrubal Cabrera

|

| Date |

Inning |

Leverage Index |

ΔWE% |

Implication |

| 09/22/16 |

11 |

4.42 |

82.5% |

0.5 gm ld in WC |

|

Statcast

|

| Exit Velocity |

Launch Angle |

Distance |

| 102 mph |

28.50 |

393 ft |

Le Flip

How about in slow motion?

Ejaculatory!

How many of his teammates do you think saw that flip? They may have seen the tail end of it, but I’m willing to bet zero saw the flip in its entirety because everyone in the dugout was gazing at the ball in flight. But this was a no-doubter. Edubray Ramos resigned to the outcome likely before the ball had reached its apex. The Phillies weren’t playing for anything at this point, but the Mets? Before this pitch, the Mets were tied with the Giants and Cardinals for the top wild-card spot. Before this pitch, in the 9th inning, Jose Reyes erased a two-run deficit with a home run of his own, only to see that lead given up again when Jeurys Familia and Jim Henderson allowed two runs to score in the top of the 11th. After this pitch, this game ended and they had a half-game lead on any team in the National League for the first wild-card spot. That bat flip is a team effort. There’s some “I did it” in there, but the way he looks towards the dugout and offers his bat up towards his teammates makes this feel like “We did it!”

The numbers:

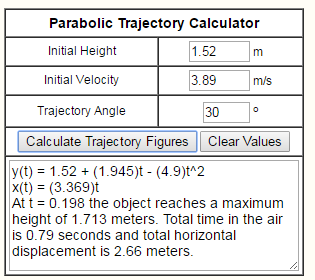

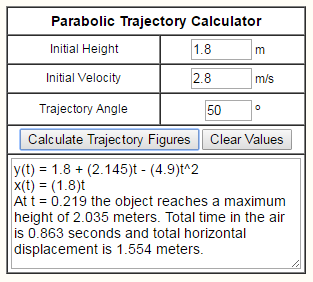

Cabrera is listed as 6′ tall. On the freeze frame I measured, he’s 1.9″ tall. So our key tells us that 1″ on the screen is 37.9″ in real life. When he releases the bat, he does so from about shoulder height and we’ll call 5′ (1.52 m) in real life. The acme is, it appears, not a great deal lower than the top of Asdrubal’s head, so we’ll tally that down at 5′-7″ (1.71 m). To me, the launch angle looks to be right around 30 degrees, and we’ll refine this number once we get them in the parabolic trajectory calculator. The duration of flight I’m using is the average number I’ve come up with through timing the video 10 times — 0.79 seconds.

Parabolic Trajectory Calculator:

|

BatCast

|

| Exit Velocity |

Launch Angle |

Acme |

Distance |

| 8.7 mph |

30 Deg |

5’-7” |

8’-9” |

Exhibit B – A Man Possessed:

|

Matt Adams

|

| Date |

Inning |

Leverage Index |

ΔWE% |

Implication |

| 07/22/16 |

16th |

1.71 |

42.7% |

2nd straight walk-off for Cardinals |

|

Statcast

|

| Exit Velocity |

Launch Angle |

Distance |

| 105.8 mph |

28.34 |

444 ft |

If this picture was part of an emotional intelligence quiz, I’m sure the answers given as to what facial expression is being displayed would vary greatly. To accurately assess the information in this picture it may behoove one to understand that, in baseball, home teams wear white and that the man in the background is most likely a fan of the home team and that his hands are held high in jubilation. If you’re only looking at the horrifying ogre in the foreground who appears to be screaming at 67 Hz+, the pitch only a dog can hear, you’d be hard-pressed to say that is a happy man. In fact, he may not be happy yet — he’s likely evoking a form of relief, having just exorcised the demons one faces when up to bat in the 16th inning of a tie baseball game; he looks like pure adrenaline. Most of us don’t get to experience a moment like this in our lifetime so we don’t have a really strong reference point for what he’s feeling, but luckily you know what this article is about and there’s a gif:

PUMP! PUMP! PUMP IT UP!

That’s all lizard brain right there. It’s a little undignified, but that’s the beauty of it. Matt Adams is a dense, hulking man, and that makes it a little scarier and a little sillier. Look:

Sassy.

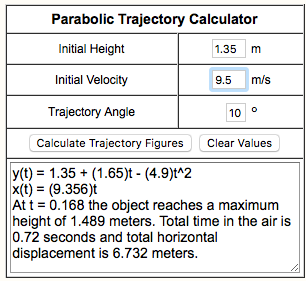

The numbers:

This one is especially hard to measure because of Adams’ primitive (yet graceful) movements. I extracted these numbers using the still image and the video:

|

BatCast

|

| Exit Velocity |

Launch Angle |

Acme |

Distance |

| 20.6 mph |

10 Deg |

4’-11” |

22’-1” |

Exhibit C – Into the Batosphere

|

Yoenis Cespedes

|

| Date |

Inning |

Leverage Index |

ΔWE% |

Implication |

| 08/29/16 |

10th |

1.23 |

47.0% |

The first baseball bat in outer space (for America – Korea has several). |

|

Statcast

|

| Exit Velocity |

Launch Angle |

Distance |

| 101.9 mph |

28.33 |

416 ft |

Yoenis Cespedes made it into my BatCast segment last year with his nifty flip in the NLDS. This flip follows a similar trajectory but he varies his look this time with a cross-bodied toss. It’s rude:

“Hold my drink, bitch.”

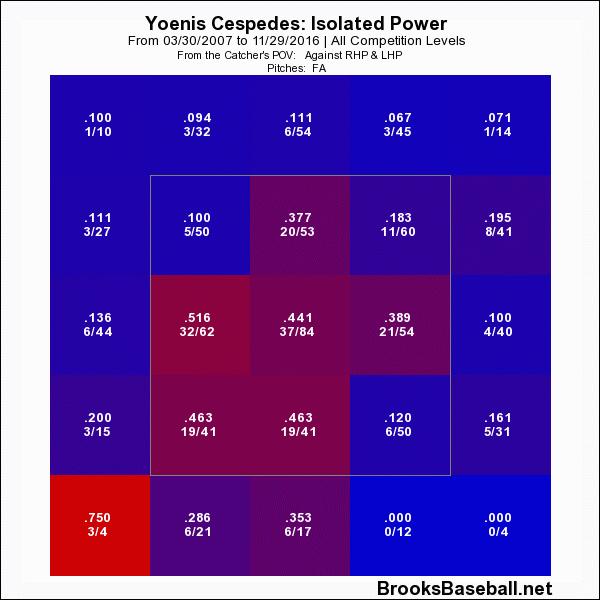

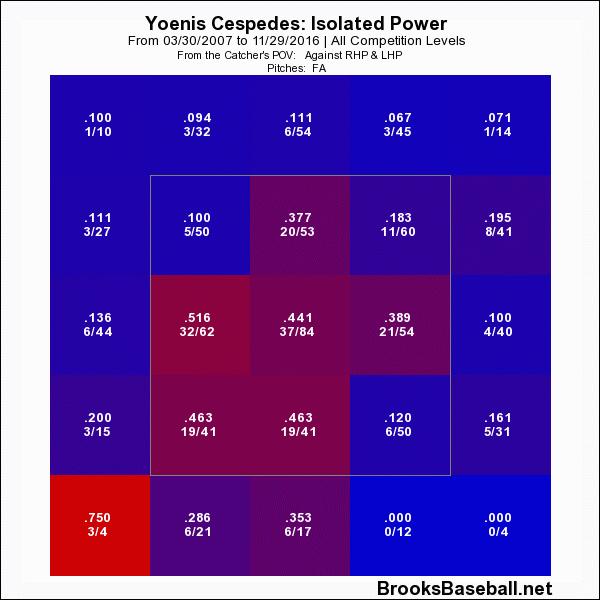

While the lesson here is obvious, the mistake is not as easily avoided: get the fastball ball UP and in on Cespedes.

Because of the evidence we have, the numbers for this bat flip will be even more rough than the others — by the way, I hope you’re not a mathematician, and I apologize if you are. The data we can gather is the launch angle and at what time stamp the bat reaches it’s highest point. Here’s a better view of the angle:

Can we agree on shoulder height for the initial launch height to make things easier? Let’s call it 5′ since Cespedes is 5′-10″. We’ll say the bat was launched at a 70-degree angle and in the gif the bat appears to reach it’s apex at just before 0.4 seconds.

|

BatCast

|

| Exit Velocity |

Launch Angle |

Acme |

Distance |

| 9.2 mph |

70 deg |

12’-6” |

4’-11” |

Exhibit D – The “I probably didn’t even need this bat to hit this home run” flip

|

Bryce Harper

|

| Date |

Inning |

Leverage Index |

ΔWE% |

Implication |

| 09/10/16 |

8th |

3.63 |

30.5% |

Bryce’s helmet probably won’t fall off when he’s running the bases. |

| Statcast |

| Exit Velocity |

Launch Angle |

Distance |

| 99.7 mph |

26.39 |

377 ft |

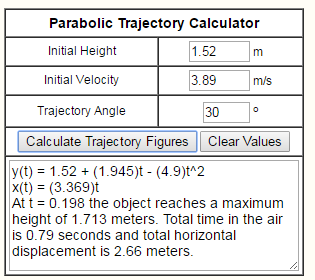

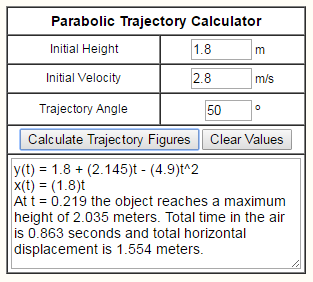

After my long-winded intro it’s fitting to get to feature Bryce Harper in this piece. He probably didn’t have as much fun this year as he did in 2015, but he appears to have gotten some enjoyment out of this shot.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I believe that is what the kids call “Swagadoscious.” I’ll just get right to the point this time.

|

BatCast

|

| Exit Velocity |

Launch Angle |

Acme |

Distance |

| 6.3 mph |

50 deg |

6’-8” |

5’-1” |

Those are the ones that stuck out to me as the best flips of the year and I hope you were able to move past the rough estimates and get some enjoyment out of that as well. I should note that Joc Pederson’s bat flip in the NLDS is omitted because I cannot find substantial evidence of an acme or distance. And while a lefty going across his body like he did is pretty exotic, the uncertainty he exudes, combined with his panicked sashay, makes this effort pretty uncool.

(Scherzer looks super imposed here)

So what can we pretend to glean from this? Based on WPA, it’s probably not surprising that Harper had the most disproportionate bat flip. Looking at the Statcast data, Harper’s home run was also the “weakest” out of the group. So I guess even if Bryce Harper says what he says just so he can get away with being a little douchey, he’s holding up his part of the deal. Of course, bat flips aren’t what make baseball fun. Baseball is fun because we can see so much of our own lives in the game — it’s the humanity. It provokes endless curiosity and it will reward you if you know where to look. It’s the only game that can end, not because of time, but with one swing, and flip, of the bat.

Don’t be afraid to clue me in to bat flips in the future — my Twitter handle is in my bio (below).