The 2016 Texas Rangers finished with just 82 wins. With an aging core and a desiccating farm system, the Rangers are drifting toward baseball’s Sargasso Sea of medioc-

What? You say the Rangers won 95 games last season?? Get on with your bad self!

Hmm … diligent research has revealed that the Rangers did indeed win 95, despite a microscopic run differential of +8, the lowest positive run differential in the majors last year. That wily Pythagoras pegged the Rangers at 82 expected wins last season, and perhaps unsurprisingly, FanGraphs currently projects the Rangers to win, yes, 82 games next season. A modest uptick in offense (due in significant part to having Jonathan Lucroy available for the whole year) will be offset by a modest erosion of the Texans’ already leaky run prevention. With an aging core and a desiccating farm system, the Rangers are drifting toward baseball’s Sargasso Sea of mediocrity, a team neither good enough to challenge for a playoff spot, nor bad enough to enable Total Roster Makeover.

For public consumption at least, Rangers’ GM Jon Daniels is acting like he has a 95-win team on the roster, throwing out speculation that the team may be after Andrew McCutchen, Edwin Encarnacion, or perhaps even Chris Scissorshands. Daniels is, on the evidence publicly available, a rather capable individual, and it is difficult to believe he is ignorant of the true state of his team.

He has a core of four 3+ win players (Yu Darvish, Cole Hamels, Adrian Beltre, and Lucroy), none of whom is younger than 30. They have some young guys with upside (Rougned Odor, Nomar Mazara, Jurickson Profar, Joey Gallo), a glove-first shortstop whose contract won’t end until after humans have colonized Mars, and Shin-soo Choo, who has become the fragile platoon corner outfielder that many feared when he signed his own post-Mars-colonization deal.

Fortunately for the Rangers, their roster weaknesses are glaring. They have four positions (1B, CF, DH, and 5th SP) that each project to amass fewer than 1 win. These should be the focus of Daniels’ attention. Let’s take them in turn:

1B/DH

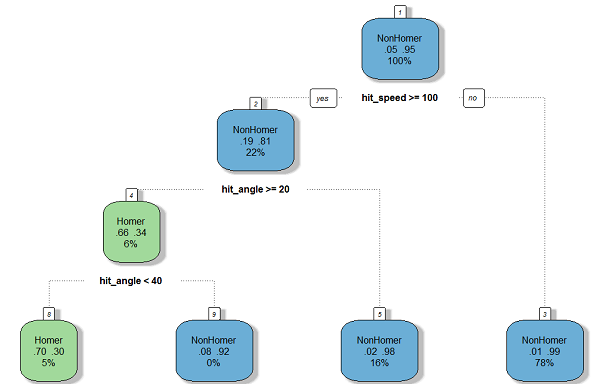

I’ll consider these together, because the Rangers can fill one of these positions with Joey Gallo, if they don’t trade him. Gallo is a true baseball anomaly, and his big-fly-big-whiff profile has been well chronicled. He had a 34.6% strikeout rate in AAA last year, a rate qualifying hitters exceeded only twice in the majors since 2007:

Mark Reynolds 2010 35.4%

Chris Carter 2013 36.2%

And the bad news is that neither of these whiffly guys broke 30% in their minor-league careers (leaving out a very short appearance in AA by Reynolds). So Gallo walks (and homers, and strikes out) alone. If the Rangers really were a 95-win team, they would probably be best served by moving Gallo for whatever they could get, which would undoubtedly be a useful return. A 95-win team can move a prospect for an overpriced veteran who will nevertheless put them over the top. But that team is not the Rangers, who are probably better off seeing what they have in Gallo, working him into the lineup as soon as practicable. But Rangers fans beware! No windshield in the Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington metropolitan statistical area will be safe.

That still leaves a big hole at the other position. Profar could play first, but his bat likely won’t be able to carry the position, at least not yet. Encarnacion wants a megacontract, and while the Rangers may be able to afford the cash (they have the eighth-highest payroll in the AL next year, and they have a Texas-sized TV contract) the contract length will be brutal. Encarnacion recently turned down 4y/$80m from the Blue Jays, so he’ll presumably want more than that from the Rangers (or anyone else). Thanks to the qualifying offer, he’ll also (for now, at least) cost a first-round pick. While he obviously would provide some short-term help for the Rangers, adding a very expensive and declining veteran on a long-term deal probably isn’t the kind of move an 82-win team should be making.

Last season, E5 had his worst wRC+ and ISO since 2011, and his worst K% since 2009. Next year will be his age-34 season, and while even a decaying Encarnacion can help a team, his punishing contract is likely a better fit for a team that already has almost every other piece in place. For all his gaudy counting stats, E5 projects as just a 2.4 win player next year. The Rangers can probably get better results by spreading his putative salary over a larger number of players and a lower number of years. A platoon of Steve Pearce and Pedro Alvarez at DH could be the bargain-hunter’s option here. And let’s not overlook Ronald Guzman, who had a breakout season in AA last year (.825 OPS) before struggling in 95 plate appearances at AAA. He’s not a top prospect, but he’s still only 21, and he could be a useful piece later in 2017.

CF

The conversation probably starts with McCutchen, who appears to be a good buy-low candidate from a Bucs team that obviously wants to sell. Cutch has a team-friendly deal and a reputation as a glue guy, but the key questions are (a) will he ever hit again and (b) will he ever field again? The Rangers are going to have start restocking the farm soon, and giving away what remains of their young talent for McCutchen seems shortsighted unless they are convinced they can fix him (or that he can fix himself). Steamer, for what it’s worth, sees a significant bounceback.

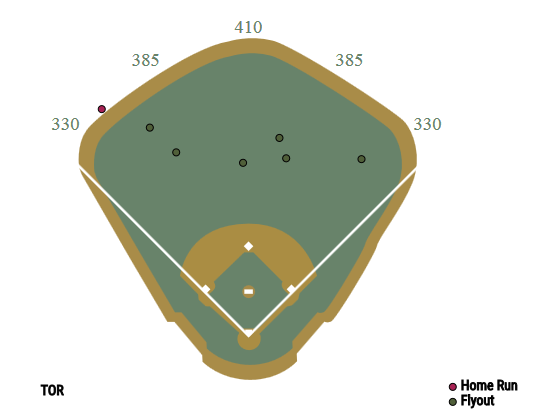

Carlos Gomez presents a (much) less exciting option, but also one that will only cost money, and perhaps not in excessively painful amounts. If the Rangers believe that his health has returned for more than a minute, Gomez could fill the bill, but most of the value he has is likely to be on defense, and the Rangers did not have an especially fly-prone staff last year (nor will the addition of Andrew Cashner change that much).

Dexter Fowler raises some of the same issues as Encarnacion, though on a smaller scale. Although he put up adequate defensive numbers last season, most metrics have seen him as a below-average center fielder throughout his career, and he will surely want more years than make sense for the Rangers’ current position on the development curve. He’ll also (for now) cost a first-round pick. All of the above is true with even greater force with respect to Ian Desmond. The Rangers should make sure he becomes someone else’s problem next year.

If the Rangers can somehow swing a trade involving Profar and one or more lesser prospects for McCutchen, then that might be the best plan. (I’m not forgetting Marcell Ozuna here, but I’m assuming he’ll cost even more in prospects than McCutchen, and I’m not assuming he’ll be able to retain his OBP progress from last year.) There are no great options here, but the lower-risk move is probably to sign Gomez.

Starter 5

A.J. Griffin is currently slated for the cannon-fodder spot in the rotation, and this year’s free-agent pitching class is legendarily bad. Rich Hill could be a perfect fit, given that he won’t ask for too many years and is having a late-career resurgence that may only be explicable with reference to the dark arts. As a fly-ball pitcher, however, he would need help in center (e.g., Carlos Gomez), and he might cough up a few more homers than last year. And he’s obviously an injury risk, but that will be priced into the deal.

Ivan Nova (!) is probably the next-best option. Steamer projects a 2.3-win season, in line with what he achieved in 2011, 2013, and last year. I’ve never been a big Nova fan, but the Rangers don’t have a lot of options here, so he may be a decent plan B if Hill signs elsewhere. And that Top-100 prospect, southpaw Yohander Mendez, has put up good minor-league numbers across six levels (counting the three A levels separately): a collective 2.46 ERA over 292 innings, and an 8.6 K/9. He’ll also be just 22 next year. While probably needing a bit more seasoning, he could reach the rotation in next season’s second half if (when?) Cashner or Martin Perez falters, or Hill gets hurt.

* * *

The 95-win Rangers were an illusion, and their chances of standing toe-to-toe with the Astros in the 2017 AL West are slim indeed. Instead, they need to start preparing for the post-Beltre era. They have some good young talent in place and a front office that has shown aptitude for acquiring more. They can attempt to sneak into the playoffs this year at relatively low cost, while retaining a cadre of young talent with which they can challenge the Astros’ AL West dominance in the years to come. Or they can act like a 95-win team. Sometimes it’s better to take the medicine.