We have seen an incredibly high number of Tommy John (TJ)[1] surgeries undergone already this season. The surgery is on pace to surpass any single-season total in history. This signifies that an unusually high number of pitchers have already gone under the knife and it is still just the first month of the season. Even with so many talented pitchers being sidelined for a season because of TJ, we have also seen league-wide offense falloff quite a bit. There are many reasons for each of these trends, and also many potential solutions, but I feel that the best solution to each problem is to lower the pitcher’s mound. I do not believe pitchers should pitch from a flat surface, which is even with the batter’s level. However, I do believe the mound should be lowered to just 6 inches above the plate. It may seem extreme or irrational, but it has been done before and it would help both issues that professional baseball is facing. One obstacle to finding a way to slow or prevent TJ is the procedure’s high success rate. It is also a difficult problem to solve because it is unclear what causes the injury and when exactly the injury begins. Nevertheless, these should not prevent the MLB from attempting to limit the growing number of pitchers requiring TJ surgery, especially when it can also increase the league’s offensive production.

24 pitchers have needed TJ surgery already in 2014, which has yet to complete its first month of regular season games. For reference, 28 pitchers received the procedure in all of 2013, and only 7 had undergone the surgery at this point last year. It is not surprising to see an increase upon last year’s total, as 2013 was actually a decrease upon 2012’s total of 55 TJ’s for pitchers. However, even in 2012, there were only 15 TJ surgeries by this point in the season. The procedure has been widespread in baseball for some time now, and it has saved many careers, which has made finding a solution unnecessary. Even with the surgery’s outstanding success rate, the time has come for the MLB to step in to protect its players.

Among the many factors that have influenced the increase in TJ surgeries of late is the procedure’s success rate. One study, completed in 2013, found that 83% of pitchers to undergo TJ return to the Majors and 97% return to pitch, at least in the Minor Leagues.[2] This success rate would not necessarily impact players that have a completely torn Ulnar Collateral Ligament (UCL), as they would have no other options to return to the mound, but it may influence pitchers with a partial tear of the UCL. In the past, many of these pitchers would turn to rehab instead of undergoing TJ. Adam Wainwright is a great example of this, as he rehabbed from a partial tear of his UCL, before undergoing TJ surgery 6 years later when he completely tore his ligament. However, because of the success of the procedure, there is little motive to attempt a rehab that may not work, and only delay the surgery, which pushes back the return date. As the Cardinals former team physician and orthopedic surgeon, George Paletta, said, “It’s become an accepted side effect of the job”.[3]

Another reason that is often cited is pitchers are initially beginning to injure their arms in youth baseball. High School pitchers are often pitching in showcases or in front of scouts, which puts extra pressure on them to throw as hard as they can and often pitch even when their arm in not entirely recovered from their previous outing. This was not the case as recently as 15 years ago, as High School showcases did not become common until the early 2000’s. This is one of the early waves of young pitchers that are reaching the Majors after going through the showcase process. From now on, the most, if not all, of the pitchers that reach the Majors will have been through this rigorous process.

Another issue facing young pitchers is that many of them are pitching in competitive games nearly year-round. Overuse is one of the many reasons pitchers experience arm injuries and pitching throughout the year has greatly increased the amount of use on pitcher’s arms. Once, many high school baseball players played multiple sports and were able to take time off from throwing; however, many pitchers now throw year-round without many breaks from throwing. Youth pitchers are also putting more stress than before on their arms because they are throwing harder than ever. This may seem to be a good thing, and it is for performance, but it puts extra stress on their ligament that is not fully developed. Dr. James Andrews says that High School pitchers throwing between 80-85 mph are in particular risk of arm injuries because they are putting too much stress on a ligament that has not developed enough. As Lindsay Berra explains, a pitcher does not rupture his UCL on one pitch:

Strasburg was probably in trouble from the get-go. He didn’t rupture his UCL on one pitch with the Nationals — even if a pitcher feels a pop on a particular pitch, his UCL was anything but pristine before the incident. Like a rope, Strasburg’s UCL probably started to fray the moment he began pitching off a mound, the extra height of which can compound the stress of each pitch. It likely got worse not only because of his mechanics. Kids who throw the hardest pitch the most: they get hitters out.[4]

While it is clear that TJ procedures are increasing, the exact cause of TJ is not clear, as many factors impact whether people require TJ. However, it is evident that pitching off a mound increases the stress put on the pitcher’s arm. Comparing just the number of TJ procedures for pitchers and for position players, it is clear there is a substantial difference. Since the first TJ surgery in 1974, 622 pitchers have undergone the procedure, while only 41 position players have received the surgery. There are more differences than merely the mound, but none of them account for such a large discrepancy between the two types of players.

Another common comparison for anecdotal evidence is pitchers compared to quarterbacks in football. According to a study in 2010, there had been 10 reported instances of NFL quarterbacks with damage to their UCLs, yet only one of these players underwent surgery. The other nine quarterbacks chose to use therapy to repair their injury and their mean number of days until their return was 26.4 days.[5] As with the differences between pitchers and position players, there are numerous differences between quarterbacks and pitchers. However, these differences do not account for such a significant gap between both UCL injuries and TJ surgeries.

Both of these examples contain too many confounding variables to draw any significant conclusions. However, a study completed in 2008 examined the effects that the 10-inch mound has on a pitcher’s mechanics and the stress that it puts on the pitcher’s arm in comparison to a mound at 8 inches, 6 inches and flat ground. The study, led by William Raasch, selected 20 from MLB organizations and Milwaukee-area NCAA Division-1 pitchers. The study found that pitchers throwing from a 10-inch mound compared to pitchers throwing from flat ground experienced extra stress on both their pitching shoulder and elbow.[6] They found that the greatest difference was at foot strike, as the mound changes the timing of the foot strike compared to the position of the pitcher’s arm. This study found that pitchers definitely experience more stress on their arm when throwing from an elevated surface than from a flat surface.

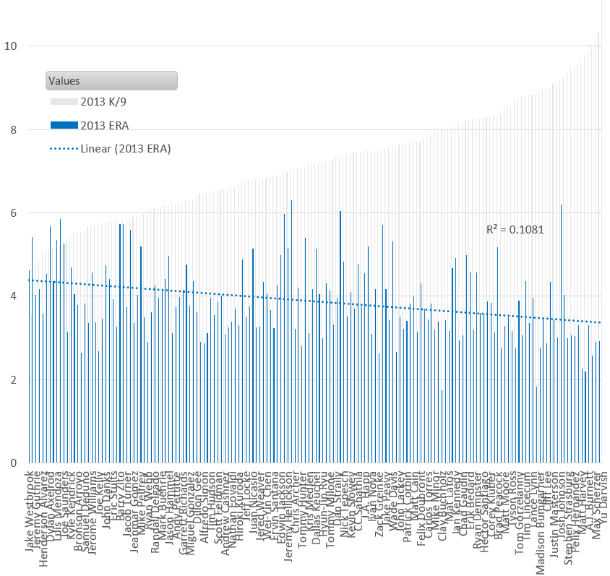

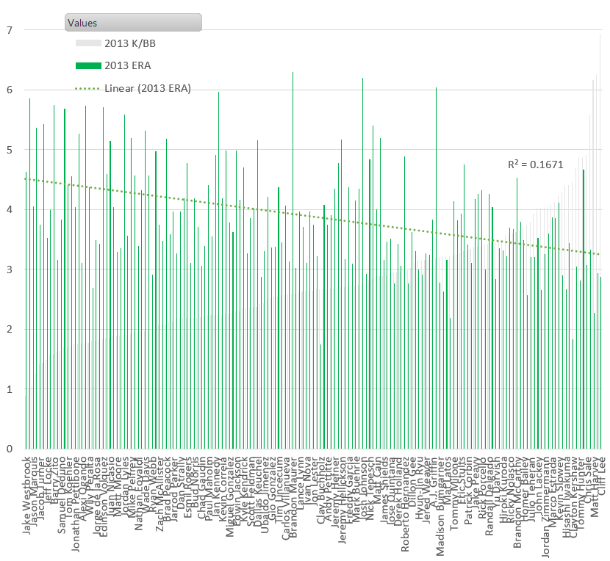

While the majority of this post has been dedicated to the effects the mound has on a pitcher’s health, lowering the mound will also improve the offensive production in the MLB. Of course, when the mound was first lowered to 10 inches in 1969, it was done in order to improve offense. After “The Year of the Pitcher” in 1968, the MLB saw the average runs scored per game increase by .65 in just one season. It is clear that lowering the mound had a significant impact on the league’s offensive output. Once again, we are in need of the mound to be lowered in order to improve the league’s offense. With better pitchers, defensive shifts and, most significantly, more stringent testing for Performance Enhancing Drugs (PEDs), we have seen a sharp drop off in offensive performance. In 2013, the MLB R/G (4.17) was the lowest it has been since 1992 (4.12). This is not just a single-season aberration, as it has been experiencing a steady decline since 2006, when it was at 4.86. HR/G are also down quite significantly since 2006, when it was 1.11, and were just .96 in 2013. Easily the largest difference between 2006 and 2013 is the increase in strikeouts per game, as they have skyrocketed from 6.52 to 7.55 in 2013. By lowering the mounds, the MLB will be able to improve upon these numbers and return offense back into baseball.

Lowering the mound may seem to be a radical step to solve two things that some people may not seem like problems; however, it is the best of the few options the MLB has. While some will argue that this will not limit TJ procedures because many pitchers are already damaged goods by the time they reach the Majors, this is a change that will soon reach the NCAA, High School and youth baseball leagues if the MLB does it. This will have a profound impact on the number of TJ procedures once these pitchers reach the Majors, as they will have reduced the stress on their arm over a long period of time. The impact will not be immediate in the MLB, but when the next wave of young, talented pitchers reaches the Majors, there will be fewer TJ procedures.

The immediate impact will come from the increase in offensive production, as the lower mound will take away some of the advantage from the pitchers. As I have mentioned above, there are not many appealing alternatives. The most common solutions to the low offensive numbers is to juice the baseballs, similar to what Japan did this past season. While this would certainly improve offensive production and be less costly than changing the mounds, it would not help decrease the number of TJ procedures. A bit more radical of an alternative, that I do not believe could ever happen, is the MLB allowing the use of PEDs. While this would likely increase offense, it would almost force players to take PEDs or else they would be at a disadvantage to the rest of the players that do take PEDs. It is not fair to put athletes in this position, especially when we know how detrimental steroids can be to a person’s health.

Another option is to add a DH to the National League, which has been discussed and is quite possible. However, this also fails to help pitchers avoid TJ. Also, in 2013, the NL averaged just 4.00 R/G compared to the AL’s average of 4.33 R/G. Assuming the NL’s production would match the AL’s, the addition of the DH would add just 802 runs to an MLB season. When the MLB first lowered the mound in 1969, the league scored 2,527 more runs than the previous season and that was with only 24 total teams. By lowering the mounds again, the increase in offensive production would substantially increase beyond where it would with the addition of a DH in the NL. Among these options, I believe the best is to lower the mound to 6 inches above home plate.

The number of TJ surgeries continues to rise and it is time to make an attempt to limit this procedure. The best way to do this is to lower the height of the mounds in the MLB, as this will decrease the stress that pitchers suffer when they pitch. Once the MLB does this, all other levels of baseball will follow suit, just as they did in 1969. The purpose this time; however, will be two-fold, as the lower mound will also serve to take away some of the pitcher’s advantage, and therefore, improve the MLB’s offensive numbers. Knowing what we know about the mound’s impact on a pitcher’s mechanics and the extra stress that it exerts on the pitcher’s arm, we cannot idly watch as more and more pitchers suffer through a year of rehab from a surgery that can be limited.

[1] http://www.baseballheatmaps.com/disabled-list-data/

[2] http://www.newsday.com/sports/baseball/study-shows-pitchers-who-get-tommy-john-surgery-almost-all-pitch-again-1.7621000

[3] http://espn.go.com/mlb/story/_/id/7712916/tommy-john-surgery-keeps-pitchers-game-address-underlying-biomechanical-flaw-espn-magazine

[4] http://espn.go.com/mlb/story/_/id/7712916/tommy-john-surgery-keeps-pitchers-game-address-underlying-biomechanical-flaw-espn-magazine

[5] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20609599

[6] http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/03/080323210203.htm