Mark Reynolds’ Whiffs by Pitch Type

Mark Reynolds is perhaps one of the more interesting power hitters heading into his prime this season. He has led the entire league in strikeouts since 2008, holding the all-time record for most strikeouts in a season with 223 K’s last season.

This year, he leads the league once again in strikeouts, as well as perennial leader in swinging strike percentage. He has whiffed on 17.3% of all pitches this season, second place being Ryan Howard at 14.4%. Interestingly, Reynolds does not actually swing at everything a la Jeff Francoeur (60.7% swing percentage) and is barely in the top 50 in percentage of pitches he swings at with 46.8%. This makes it even more amazing that Reynolds leads the league in strikeouts and swinging strike percentage regularly without even taking that many swings. That’s a lot of whiffing going on, and I do suppose that the rare times he does connect the bat to the ball, he hits it hard.

I wanted to know more about Mark Reynolds’ swinging strike percentages to see how he fares against certain pitch types by handedness. Of the five main pitch types, fastballs, sliders, cutters, curveballs, and changeups, Mark Reynolds has seen cutters less than 200 times since his debut, 139 cutters from right-handed pitchers and 41 cutters from left-handed pitchers. He has seen at least 200 pitches for the other pitch types for right-handed pitchers or left-handed pitchers. Ignoring cutters due to small sample size, I will take a look at Reynolds’ swinging strike percentages against four-seam fastballs, sliders, curveballs, and changeups.

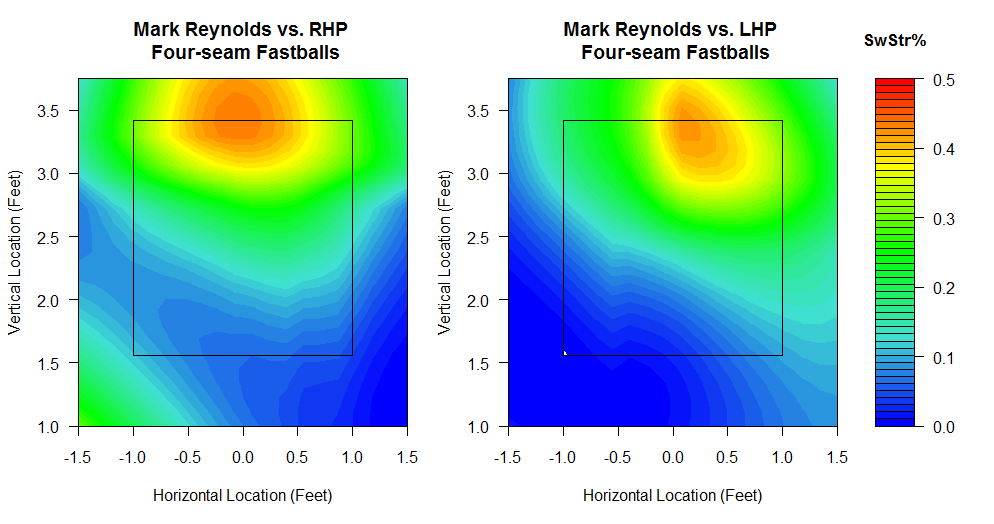

Let’s take a look at Mark Reynolds’ swinging strike percentages against four-seam fastballs split by RHP and LHP (1435 pitches from RHP, 468 pitches from LHP):

Here, it looks like Reynolds falls victim to high fastballs from both right-handers and left-handers. For Reynolds, he whiffs on the outside fastball from LHP stick out as well as the low and inside fastball from RHP.

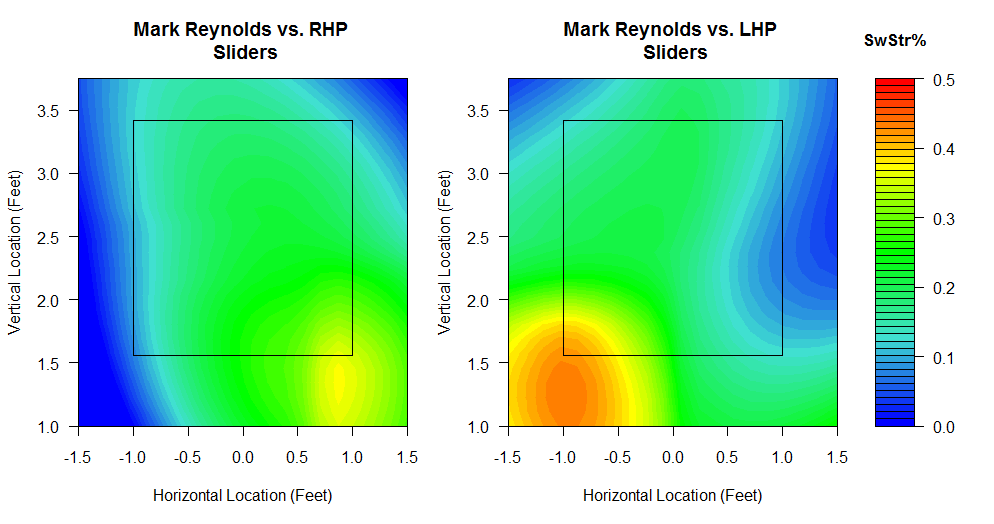

Here’s a look at Reynolds against sliders (1542 from RHP, 224 from LHP):

This is interesting. Reynolds strikes out far more against right-handed pitchers than against left-handed pitchers, but he tends to swing at (and miss) sliders coming from LHP more than he does from RHP. LHP sliders come low and inside while RHP sliders go low and outside, but even LHP sliders coming in from low and outside are swung at and missed by Reynolds.

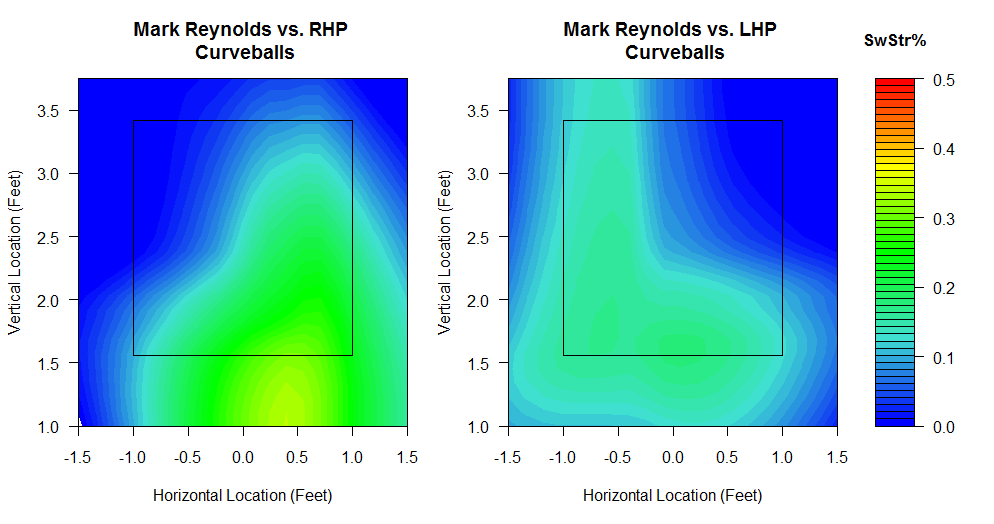

Curveballs against Reynolds are a whole different story (567 from RHP, 228 from LHP):

Here, Reynolds clearly struggles at connecting on curveballs from right-handed pitchers, some in the strikezone and most low and outside the strikezone. Curveballs from LHP also get Reynolds to whiff sometimes on the inside part of the plate as well as the lower part.

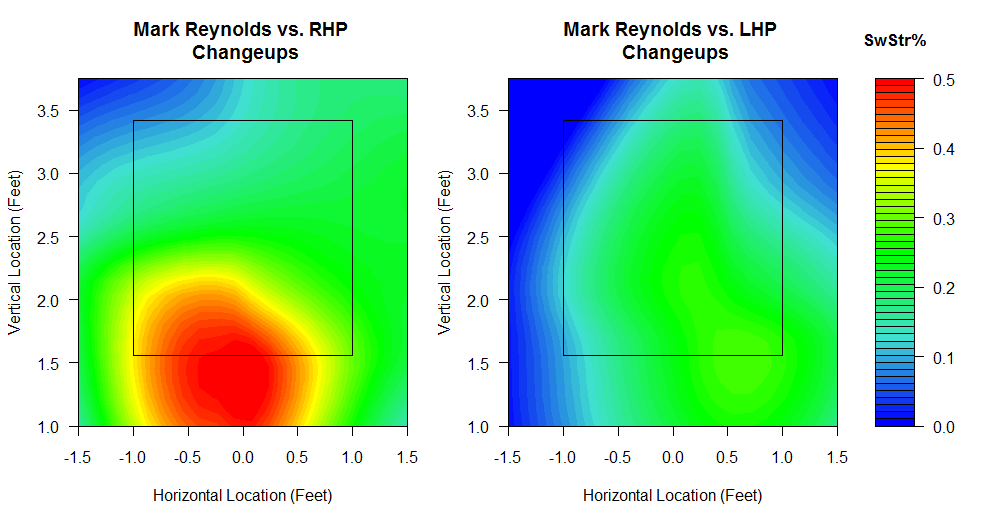

Finally, here’s a look at Reynolds against changeups, which look like his greatest weakness when it comes to missing pitches (430 from RHP, 338 from LHP):

This is very telling. The splits against changeups are very different, as Reynolds whiffs on over 50% of changeups from right-handers that are located on the edge of the strikezone at the bottom. This is much different from LHP changeups, where any spot doesn’t look to cross over 30% whiff rate, except the lower righthand corner of the zone. What’s also crazy about this is that when you look at Reynolds against changeups in general, he misses at around 20% of nearly all changeups low outside and nearly all areas within the strikezone as well.

From these plots, there are characteristics of Reynolds’ swinging strikes that are similar to conventional thought and common knowledge, such as chasing high fastballs or low breaking balls. But the key to exploiting Reynolds’ weakness at missing the ball when swinging is definitely throwing timely changeups, especially from right-handed pitchers, while it seems that Reynolds is less prone to whiff against LHP curveballs the most.

This article was originally posted at Think Blue Crew, a blog dedicated to data visualization of baseball, basketball, and football statistics. Check it out for more f/x visualizations like this.