How Much Have Young Pitchers Contributed to the “Year of the Pitcher”?

There has been plenty of talk this year comparing 2010 to 1968, also known as the Year of the Pitcher. While I believe the comparison is a bit farfetched, there is an aspect of this discussion that does grab my attention. This renaissance is being led by a young group of pitchers such as Ubaldo Jimenez, Josh Johnson and Stephen Strasburg, and is a group that many are considering to be one of the best of all time. After seemingly going through somewhat of a dry spell during the early 2000’s, it appears that the latest troupe of pitchers has arrived en masse. Many people are comparing this group to the vaunted group of pitchers that debuted in the late 1960’s, including Hall of Famers Tom Seaver, Steve Carlton, Fergie Jenkins, Jim Palmer and Don Sutton.

I am a big subscriber to the theory that people think whatever is happening in the present is the greatest event of all time, so I decided to compare just how good the young pitchers of this generation were compared to their counterparts from years past. I took a snapshot of Major League Baseball right now in 2010, as well as the end of the 1970 season and the 1990 season. 1990 was chosen because it was halfway between the two year’s in question, and would give an indication of whether or not the late 1960’s and today’s era were special or just the norm when it comes to young pitchers. Using the Baseball Reference Play Index, I identified the pitcher’s age 27 and under who I thought had accomplished the most prior to the given years. In my analysis, nothing that happened after the cut-off years is taken into consideration; I just want to know how good these pitchers were at the given dates. Also, please keep in mind the era’s, as the ERA numbers from the 1970 group are not as impressive as you may think. It was just not worth it to calculate the ERA+ of each player to illustrate my point, especially thanks to the presence of WAR, and I think most of the people reading this are smart enough to realize that a 3.50 ERA in 1970 is not the same as in 2010. All WAR data prior to 2010 is from Rally’s WAR database, and 2010 information is from FanGraphs.

1970

Reading through the names on this list is pretty impressive. However, when you look at the numbers they lose some of their lustre. For example, at the end of the 1970 season, Don Sutton was 25 years old, owned a career record of 66-73, and had only posted two seasons with an above average ERA, the best being a 110 ERA+ in 1966. Hardly Hall of Fame material. Many of these players went on to have very successful careers, but the fact of the matter is it is highly unlikely that people in 1970 were talking about a golden age of young pitchers. Relative to the rest of the league, there was not much special about these guys outside of a select few, which can be seen by the average WAR/200 IP of 2.93. The majority of them had their best seasons after 1970, as evidenced by the presence of only two Cy Young Award winners.

1990

As you can see, this list is much shorter, and there certainly was not as much young pitching depth as twenty years prior. However, the quality is far superior, as the ERA’s are very impressive when compared to league average, and the average WAR is higher than 1970 by .72. This group includes four Cy Young Award winners, and Roger Clemens was just entering his peak. Time has not remembered this group as kindly as there is only one slam-dunk Hall of Famer (Maddux), a solid HOF candidate (Smoltz) and a tarnished legend (Clemens). However, when taking a snapshot at the end of the 1990 season, I believe this group is stronger than the top candidates from 1970.

2010

Now let’s take a look at today’s players. Obviously the win totals are suppressed as players spend more time in the minors and make fewer and shorter starts. However, outside of Nolasco and Santana, the ERA numbers are very impressive, and the average WAR is slightly higher than the 1990 group. They are a little short on accolades, but I would not begrudge you if you argued that the 2010 season is not finished, and following this season we can probably put CYA-’10 next to Jimenez or Johnson, and maybe ROY-’10 next to Strasburg. This group is fairly equal to the 1990 group and I believe we have several exciting years of baseball ahead of us thanks to these guys.

Conclusion

This is certainly a very subjective topic as it is very difficult to discuss players from the past without letting their future accomplishments cloud your judgement. I have done my best to isolate this flaw by only considering data from before a certain date when each of these players was still considered young. If I had to rank these groups given the statistics shown above, it would go 2010, 1990, 1970. However, we also must remember that the pitchers from the 1960’s carried a much heavier workload. On average, they had thrown 1,075 innings while the most recent group averages only 619 innings pitched. Rating WAR on a scale of 200 IP might not also be the best measure, as these pitchers often threw more than 250 innings per season. If we change our baseline to 250 IP the average WAR jumps to 3.67, which is more in line with the other two samples.

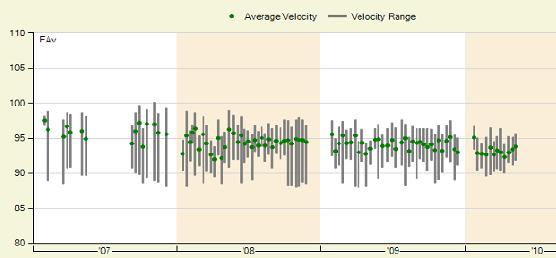

Another thing to consider is that human nature does not allow us to remember and process partial careers, and as such, most people consider the pitchers who debuted in the 1960’s as far superior to those in the 1980’s. Considering the careers that Carlton, Seaver and the rest of that group went on to have, I can understand why. If you only take away one thing from reading this article I hope it is an understanding that nobody will be able to remember exactly how we felt halfway through the 2010 season about our young pitchers. Time will make the memories murky, and ultimately, this group will be measured based on the overall success of their careers, not just what they accomplished prior to 2010. If Tim Lincecum continues to lose velocity and is done by age 30 and Stephen Strasburg blows out his arm in 2013, future generations will not be talking about all of the great young pitchers we were fortunate enough to see in 2010. Enjoy them while you can.

This article was originally published at MLB Insights. Thank you to everyone at FanGraphs, Baseball Reference, Baseball Projection and Bloomberg Sports for providing the information required for this research.